The Spiritual Geometry of Colour in Winifred Nicholson’s Early Work

Winifred Nicholson occupies a rare and radiant space within the history of twentieth-century art. Her vision was not confined to stylistic movements or the philosophical constraints of her time. Instead, she embarked on a lifelong, almost metaphysical journey into the world of color journey where light, emotion, and chromatic nuance became the foundations of her painterly language. Unlike her contemporaries who often leaned on theory or the purely visual, Nicholson saw colour as a force both elemental and sacred.

Her early works represent more than the practice of an emerging artist; they reveal a painter already deeply attuned to the symphonic relationship between light and pigment. Cyclamen and Primula (1923) stands as a landmark in her creative evolution, a painting born from both a moment of personal harmony and a peak of aesthetic sensitivity. Created during a period of profound inspiration while living in the Italian Swiss Alps, this painting doesn't merely depict flowers on a windowsill. It becomes, instead, a portal into Nicholson’s foundational philosophywhere colour breathes, resonates, and transforms ordinary domestic scenes into luminous revelations.

In Cyclamen and Primula, the structure of the composition might appear simplistic at first glance. A windowsill with delicately wrapped flowers set against a serene mountain landscape. Yet within that seemingly modest configuration lies an exquisite interplay of form and hue that borders on the alchemical. The architectural triangular tension created between the plant forms, tissue paper, and distant mountains provides more than balance, serving as a conduit for the vibrational energy of colour. This arrangement mirrors the sacred geometry found in nature and music, evoking a visual harmony that is at once structured and spontaneous.

The painting’s cool tonespale cobalt and silvery greysmelt effortlessly into one another, building a calm visual backdrop that allows more saturated colours to emerge with greater resonance. The Primula’s striking yellow, rendered with unapologetic intensity, is neither decorative nor symbolic in a conventional sense. It becomes an active presence within the painting, punctuating the visual field with a sense of optimism and alertness. Nicholson often spoke about how certain colours, particularly violet and yellow, could unlock each other’s internal light. In Cyclamen and Primula, this belief finds powerful expression. The violet hues in the Cyclamen are not simply complementary to the yellowthey ignite its luminosity.

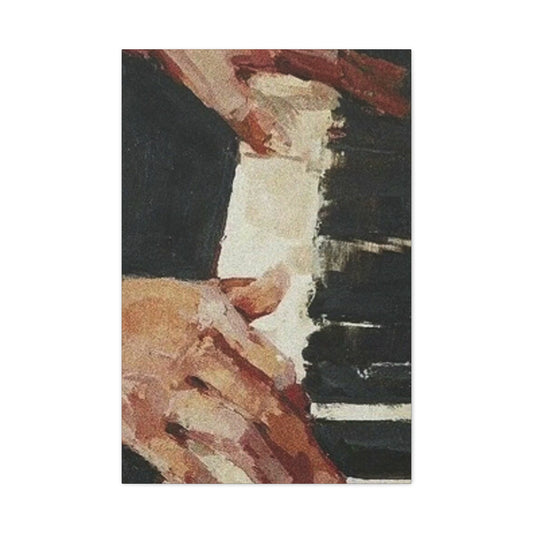

Nicholson’s tactile approach to pigment application enhances this chromatic dialogue. She allows paint to behave both as surface and as light. Translucent feathered strokes shimmer with ethereality, while occasional, deliberate impastos ground the viewer in the materiality of her vision. Her colour choices are never arbitrary. French Ultramarine brings depth and contemplation. Cerulean introduces an almost meditative stillness. Raw Umber anchors the composition with organic warmth, while Titanium White and Ivory Black offer a spectrum of opacity that moves seamlessly between the tangible and the intangible.

This sensitivity to form and tone reveals her deeply intuitive sense of visual architecture. Nicholson was acutely aware that structure in painting is not confined to linear perspective or academic proportion. Rather, it unfolds through layers of perceptual depth. In her later notes on the Mughetti series, she described a process in which shapes seemed to choose their own position on the canvas, as if arising from an emotional intuition rather than strict rationality. This interplay between geometry and sentiment sets her apartnot only as a colourist but as a visionary who sensed form as vibration.

Her roots played no small part in shaping this sensitivity. Raised in a household steeped in cultural and intellectual engagement, she inherited a reverence for the poetic aspects of the ordinary. Her grandfather George Howard, closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, impressed upon her the sanctity of everyday beauty. This legacy helped her see domestic life as flowers in a vase, a window’s light scenes of infinite artistic possibility. From the beginning, Nicholson’s canvases have spoken to a unique duality: a quiet celebration of the commonplace, paired with a nearly mystical elevation of colour.

Chromatic Alchemy and the Sacred in the Everyday

Cyclamen and Primula marks the beginning of what could be called Nicholson’s chromatic lexicona personal and spiritual vocabulary through which she explored the potential of colour not just to decorate but to illuminate. Her goal was never to replicate nature as it appeared but to extract and distill its inner light. To Nicholson, colour was not fixed; it shifted and shimmered, concealed and revealed, depending on context, light, and emotional openness.

In this pivotal work, we observe her refusal to crowd the canvas with excessive variation. Her restrained palette does not limit the expressive capacity of the work. Instead, it reveals her mastery of nuance. With just a handful of pigments, she achieves a vast range of sensationfrom the cool hush of indigo shadows to the bright resonance of lemon yellow. This economy of means becomes a form of generosity. Rather than overwhelming the viewer, she invites us to slow down, to truly look, and to feel the resonance of colour within ourselves.

The folded tissue paper within the paintinga seemingly mundane detailholds immense significance. Nicholson described the creases and folds as containing something almost cosmic, as if they veiled a secret only the eye trained in reverence could unlock. This metaphor of veiling and unveiling runs through much of her work. Colour, for her, was not an object to be applied but a presence to be uncovered.

Her manipulation of lightthrough hue, transparency, and contrastoffers a kind of spiritual dimension. By placing warm and cool tones in proximity, she creates a visual rhythm that hums with emotional resonance. The conversation between Alizarin Crimson and French Ultramarine, especially where they intersect to create burgundy shadows, demonstrates an Old Master’s sensibility with a modernist’s intention. The result is an emotional register that feels both ancient and entirely new.

Winifred Nicholson did not separate colour from life. Her work is suffused with the belief that painting can make visible what often goes unseen: the emotional and spiritual atmospheres that surround us. In Cyclamen and Primula, each elementthe floral forms, the mountain view, the creased paper, and above all the lightserves as a gateway into a deeper world. It’s not realism she seeks, but revelation. This painting doesn’t merely depict an arrangement; it transforms the seen into the felt, the visible into the experienced.

From Harmonious Union to Evolving Luminosity

At the time of painting Cyclamen and Primula, Nicholson was experiencing a creative and emotional partnership with her husband Ben Nicholson that was marked by mutual respect and fertile exchange. Their relationship, though later marked by distance and divergence, was during this period a crucible of shared artistic exploration. This painting, in many ways, reflects that harmonious visual dialogue not only between colours but between two creative minds seeking resonance in their respective practices.

Yet even as Cyclamen and Primula celebrates a period of unity, it subtly anticipates change. There is a liminal quality to the painting poised quietude that straddles figuration and abstraction, presence and absence. It offers a snapshot of a moment fully inhabited, but also on the cusp of transformation. Nicholson’s later works would carry the weight of emotional solitude, the rigor of introspection, and an increased abstraction of form. In paintings such as Flowers On A Windowsill (1945–46), created in the aftermath of personal and global upheaval, we see how the chromatic language she developed in the Alps evolved into something deepermore distilled, more resolute in its commitment to revealing the extraordinary within the ordinary.

What remained constant throughout her life was her belief in colour as a living entity. She wrote of how certain colours only revealed themselves under specific emotional or atmospheric conditions, suggesting that painting was as much about receptivity as it was about expression. This openness to the worldto its light, its textures, its silencesinfused her work with a timeless quality. In every canvas, there is the sense of an artist not asserting herself upon nature, but listening deeply to what it has to offer.

Cyclamen and Primula thus stands not just as a beautiful composition or a technical achievement but as a manifesto. It articulates the foundational principles of Nicholson’s life-long pursuit: that colour can carry emotion, that light can reveal spirit, and that even the humblest of domestic settings can contain a universe of meaning. Her work asks us to reconsider how we see, not as a passive act but as a form of attunement. In doing so, she extends an invitation to perceive colour not only with the eyes, but with the soul.

A Transformative Palette: From Personal Loss to Chromatic Freedom

In the years following the tender, crystalline stillness of Cyclamen and Primula, Winifred Nicholson’s artistic language began to shift profoundly. The end of her marriage to fellow painter Ben Nicholson did not silence her creative voice deepened it. Instead of retreating from her work, she turned more fully inward, discovering new depths in both emotional experience and visual expression. During this time, the act of painting became a means not merely of recording but of reconciling: a translation of personal change into the silent but vivid dialogue of colour.

The 1945–46 canvas Flowers On A Windowsill, created from within the familiar sanctuary of Boothby Hall in Cumberlandher childhood homestands as a milestone in this transformation. It marks a departure from the more defined realism of her earlier floral still lifes. Rather than offering a scene bathed in gentle precision, this work delivers something more elusive and emotionally charged: a conversation between memory and colour, atmosphere and feeling. The composition opens itself to interpretation in a way that suggests maturity, freedom, and artistic fearlessness.

Here, Nicholson no longer concerns herself with capturing things as they appear but rather as they are felt. Gone is the meticulous edge that once framed every petal. In its place flows a freer, windblown application of paint, a loose yet deliberate rhythm that mimics the breezes outside the window or the meandering of a quiet thought. The brushwork doesn’t just describeit breathes. With each stroke, she invites us not only to see but to feel the resonance of solitude and the stillness of moments suspended in time.

Where once clarity ruled, now resonance prevails. The visual language has changed, but it is no less articulate. Her palette, now tuned to a more introspective frequency, suggests not the absence of brightness but a new awareness of its nuances. Colours speak here not as objects in light, but as sentiments suspended in smoky, glimmering, poignant.

Chromatic Dialogues: The Dance Between Stillness and Intensity

At the heart of Flowers On A Windowsill lies a sensitive interplay of chromatic forces, a dynamic equilibrium between the cool, desaturated tones that ground the work and the fiery punctuation of red blooms that command emotional attention. The background tapestry of subdued sky and seas is rendered in a spectrum of mid to light blue-greys, likely derived from a combination of Indigo, Titanium White, and subtle infusions of Ivory Black. These tones serve more than a compositional functionthey conjure a quietude, a hush, a wistful breath of coastal air seen through rain-kissed panes.

The inclusion of Cobalt Blue Hue within the sea areas, slightly more vibrant than its skyward counterparts, adds dimension without breaking harmony. It offers the viewer a visual echo of the skydeeper, perhaps more introspective, yet still joined in conversation with the world above. This chromatic mirroring creates a sense of emotional continuity, a feeling of being enveloped by calm and reflection.

And then, the reds. Positioned with both confidence and restraint, the flowers blaze forth in Cadmium Red, not through sheer volume or texture but through pure chromatic strength. They don’t just catch the eyethey insist upon being felt. Their vibrancy cuts into the stillness, evoking the afterglow of passion, the flare of a long-held memory, or the sudden rise of an unspoken thought. Set against the canvas of quiet blues, the reds don’t just contrastthey narrate. They pulse with a kind of emotional urgency that elevates them beyond decoration to symbol.

Nicholson’s sensitivity to colour’s emotional temperature is further demonstrated by her treatment of yellow. These are not the sharp, lemony yellows of her earlier work, but warmer, deeper notestones achieved through the fusion of Cadmium Yellow with Yellow Ochre, possibly softened by dilution to let the underpainting influence their luminosity. These yellows shimmer quietly, never overwhelming. They guide the gaze through the painting, connecting the visual highs and lows with a steady warmth that recalls candlelight in a twilight room.

The pinks and purples lend yet another layer to the chromatic narrative. Subtly mixed from Manganese Violet, Titanium White, and whispers of Cadmium Red, they appear within the vase and among the petals like forgotten phrases in a lettergentle, wistful, necessary. Their presence softens the drama, serving as intermediary tones that tether the vibrant reds to the tranquil greys. In doing so, they anchor the emotional transitions of the composition, balancing visual contrast with poetic subtlety.

What emerges from all these tonal conversations is a deep sense of colour as language belief Nicholson expressed overtly in her writings, most notably in Liberation of Colour. For her, colour was not simply an element of design. It was elemental in itself, as essential as breath or love. In this painting, the red sings its solo with clarity and conviction, the blue sighs with a weighted grace, and the yellow flickers gently like hope persisting at the edge of recollection.

Light, Memory, and the Architecture of Emotion

If Cyclamen and Primula spoke to a luminous joy of light flickering through glass or snow shimmering on distant mountainsthen Flowers On A Windowsill speaks more intimately. The light here is emotional, filtered through memory and softened by experience. It is not a brilliance but a glow, a resonance, a kind of chromatic weather in which each hue has been lived before it has been painted.

In this canvas, light is not just what illuminates, but what connects. It slips through the grey sky, falls across the windowsill, touches the petals, and binds together interior and exterior worlds. Nicholson achieves this subtle orchestration through an expert understanding of atmospheric colour. The greys she employs are anything but flat: each is laced with a complex undertone of blues, ochres, and hints of red that conjure a sense of place and emotional tone more vividly than detail ever could.

Even the neutral areas window frame, the table, the air carry emotional weight. The warm grey of the frame, likely a mixture of Raw Umber, Ivory Black, and Titanium White, operates as a kind of chromatic fulcrum. It joins the warmth of the interior with the cool hush of the outdoors. Through this junction, Nicholson invites the viewer to sense not only the structure of the space but its emotional contour: the safety of the inside, the vastness beyond.

This nuanced composition reflects her ongoing engagement with abstraction. Around this time, Nicholson was creating abstract works under the pseudonym Winifred Dacre, placing herself in dialogue with avant-garde figures like Piet Mondrian. Though Flowers On A Windowsill remains figurative, its spatial logic and tonal orchestration suggest an abstract sensibility. The painting is structured like a piece of musicits architecture dictated not by line but by rhythm, hue, and silence.

Nicholson’s gift lies in her ability to capture not just what a moment looks like, but what it feels like to remember it. Each petal, each hue, is less a representation than a tracean afterimage of something once seen and now deeply felt. Her brush does not merely describe but translates, and in doing so, reveals a painter deeply attuned to the poetry of pigment.

By allowing her palette to soften, her touch to loosen, and her compositional rules to bend, Nicholson created a work that feels simultaneously precise and organic. It listens, it lingers, it exhales. Through restraint, she found radiance. Through solitude, she uncovered a profound generosity of vision.

In Flowers On A Windowsill, we see not just a still life but a lived lifeits quiet triumphs, its softened regrets, its echoing light. The painting is both a culmination and a continuation: a deeply personal affirmation of colour’s ability to hold feeling, to create presence, and to linger in the mind long after the eye has turned away.

The Quiet Miracle of Light: A Meditation on Easter Monday

In her 1950 masterpiece Easter Monday, Winifred Nicholson reaches an apex of subtlety and emotional resonance. This work emerges not as a visual transcription of a scene, but as a profound evocation of a mood that hovers delicately between stillness and spiritual illumination. Painted during a period of settled introspection in her Cumberland home, Nicholson moved beyond mere representation, capturing the interiority of both space and spirit through her masterful manipulation of tone and light.

The painting features a humble arrangement of daffodils on a windowsill, yet through Nicholson’s hand, they transcend their botanical identity to become vessels of quiet transcendence. Each petal, rendered in soft but radiant hues, seems to radiate not only sunlight but an inner warmth visual whisper of rebirth and renewal. These daffodils are not just flowers; they are the embodiment of Easter’s symbolic promise. They glow not with decorative flamboyance but with the quiet dignity of something eternal, something reborn not in grandeur but in grace.

Unlike the sharper tonal play of Cyclamen and Primula or the animated gestures of Flowers On A Windowsill, Easter Monday achieves its effect through restraint. It invites contemplation rather than demanding attention. This is a painting that breathes, that waits for the viewer to come closer, to lean into its silence. Here, Nicholson’s palette refines itself down to elemental contrasts: the self-luminous yellow of the daffodils, the contemplative violets and greys that ground the space, and the faint hum of ochres and umbers that bridge the two realms.

The interplay of these hues is more than aesthetic; it is emotional. The daffodils, likely painted with a combination of Cadmium Yellow, Primrose Yellow, and moderated by Yellow Ochre, seem to emit light rather than merely reflect it. This luminosity, however, is balancednever isolated or brash. It is enriched, softened, and made profound by the dusky violet greys formed through blends of French Ultramarine, Indigo, and Titanium White. Occasional touches of Cobalt Blue add a chilly resonance that pulls the exterior landscape into the periphery of the composition. These atmospheric tones hold the painting in a suspended stillness, evoking the hush of a northern morning just after sunrise.

Nicholson's chromatic restraint enhances the emotional register of the scene. The light in Easter Monday is not the fleeting brilliance of Impressionist canvases. Rather, it feels eternalsomething remembered, not just seen. Her brushwork reinforces this timelessness, with transitions that feel less like applications of paint and more like the slow unfolding of breath.

Interior and Exterior in Harmony: A Visual Theology of Colour

What gives Easter Monday its lasting power is its seamless integration of interior and exterior worlds. The window, often a mere boundary in lesser works, becomes a dynamic threshold in Nicholson’s hands point of communion between the room and the world beyond. The view through the window is bathed in the same tonal harmony as the flowers in the foreground, suggesting not separation but synthesis. The exterior landscape, though subdued, hums with the same spectral energy as the glowing bouquet. This mutual illumination between inner and outer spaces reinforces Nicholson’s belief in the spiritual potential of colour and composition.

At the heart of this interplay are the daffodils themselves. Their golden flames are counterbalanced by the grounding coolness of the interior: the jug with its cobalt blue pattern, the soft grey-violet shadows beneath the vase, and the gentle gleam of the curtain rings above. These brass rings, small yet significant, echo the golden notes of the flowers and act as visual anchors. Their precise placement draws the eye upward, suggesting a quiet ascent, a movement from earth to sky, from temporal to eternal.

The background colours that structure this chromatic atmosphereblends of Indigo and Ultramarine, enhanced by the cool purity of Titanium Whiteimbue the painting with a sense of sacred calm. There is no urgency in the transition between colours; instead, there is a kind of visual prayer, a devotional slowness. Even the earthy tones of the window ledge, composed of Yellow Ochre, Raw Umber, and softened with white, seem to breathe with the same rhythm as the daffodils above them.

Nicholson’s approach to painting during this period had become deeply meditative. Each colour, each shape, exists not merely to fill space but to express a quality of presence. The vibrancy of the bouquet is heightened by the muted field behind it, creating a chromatic relationship that feels not only harmonious but meaningful. These are not just complementary hues; they are partners in a conversation about renewal, fragility, and light.

The use of violet is particularly telling. Often overlooked in favour of more dominant tones, here it becomes a silent scaffolding. It doesn’t command attention, yet it holds the entire composition together. Violet forms the spiritual undertone of the piece, appearing in shadows, distant hills, and even in the subtle modeling of petals and stems. It represents not darkness but depthnot obscurity but quiet reverence.

A Poetics of Renewal: Art as Sacred Witness

At its core, Easter Monday is not simply a painting about flowers, windows, or light. It is a visual affirmation of life in its most tender and enduring form. Nicholson, always sensitive to the metaphysical dimensions of colour, channels here a kind of spiritual optimism. Emerging in the aftermath of global turmoil and war, this work does not announce itself with patriotic fervour or epic gesture. Instead, it offers a vision of soft resurrection return of light, not as spectacle, but as promise.

This painting serves as a quiet witness to renewal, its message carried not through iconography but through atmosphere. The daffodils do not stand alone as a seasonal emblem; they are integrated into a larger ecology of light and space. Their glow suffuses the entire scene, illuminating not just surfaces but emotions. Nicholson’s genius lies in her ability to make this emotional light visible to render not only the physical presence of flowers but the warmth they radiate into the world around them.

Such luminosity does not arise from exaggeration. There is nothing garish or overwrought in her palette. Instead, the power of Easter Monday lies in its restraint. The painting’s strength is in its softness, its refusal to shout. Each stroke is purposeful, considered, and laden with feeling. Her technique reveals itself through silence: knowing when to apply colour and when to let it remain suspended, untouched. These painterly decisions become spiritual acts in themselves.

This philosophy of light is what separates Nicholson from her contemporaries. While many pursued brilliance in the dazzle of sunlit moments, she pursued the glow that emerges in the hush before or after. She sought what is enduring in the ephemeral, what is sacred in the ordinary. Her light is not the glare of midday, but the glimmer of dawnfragile, reverent, and full of hope.

The window in Easter Monday encapsulates this spiritual dynamic. It is not merely a compositional tool but a metaphysical symbol. It represents both separation and unity, inner reflection and outward gaze. The flowers placed at this threshold act as emissaries between worldsreal and imagined, visible and felt. Their golden radiance is the manifestation of something greater than beauty: a gentle insistence on the possibility of renewal.

In viewing this painting, one is invited into a state of contemplation. It slows the gaze, softens the breath, and holds the viewer in a moment that feels outside of time. The experience is less like looking at a picture and more like entering a prayer. Every hue, every quiet shape, speaks of cyclesof death and return, of darkness and light, of silence and song.

In Easter Monday, Winifred Nicholson does not depict a scene; she channels an essence. The essence of a morning renewed. The essence of colour as life-force. The essence of art as a conduit for the invisible. With her restrained palette and meditative composition, she reveals herself not just as a painter of flowers or interiors, but as an artist of transcendencean artist of light.

The Spiritual Radiance of Colour: Winifred Nicholson’s Prismatic Awakening

In the final decade of her life, Winifred Nicholson’s relationship with colour underwent a profound metamorphosis. No longer confined to the boundaries of physical observation, colour became, for her, a metaphysical dialogue language through which the ineffable essence of light could communicate something deeper, more eternal. This transformation was catalyzed by a pivotal encounter in 1975 with physicist Glen Schaefer, who gifted her a simple prism. This object, delicate and precise, would go on to reshape the final phase of her artistic vision.

Through the prism, Nicholson began to perceive rainbows not as isolated arcs in the sky but as omnipresent halos refracted at the edges of everyday forms. A vase of flowers, a curtain, a windowsill all became launchpads for light’s dispersal into a spectrum of possibilities. The world before her seemed to fracture into vibrant multiplicities, and her palette evolved to reflect this profound shift. What emerged from this revelation was a luminous body of work now known as the Prismatic Paintings visual symphony in which colour itself is both the subject and the message.

Though her subject matter remained consistentflowers, interiors, and domestic stillness lens through which she saw them had utterly changed. In these prismatic canvases, forms blur into their surroundings, creating ethereal transitions between object and light. Edges dissolve, hues mingle, and the very air around objects seems to shimmer with spectral life. It’s not simply a matter of how things look, but how they feel, resonate, and breathe. Nicholson had stepped beyond representation into an illuminated realm of perception, where each brushstroke seemed to radiate from a place both internal and cosmic.

A Symphony of Pigment: The Chromatic Architecture of the Prismatic Paintings

Among Nicholson’s late masterpieces, few are as arresting as Geometric Curtain (c.1980), where her evolving understanding of colour reaches a point of vivid expression. The canvas erupts in rhythmic dialogues of turquoise, cobalt violet, geranium red, and lemon yellow colors that do not merely sit side by side but converse, resonate, and amplify one another. There is a clarity in the chaos, a harmony that hovers between serenity and intensity. Each shade is rendered not just for its own sake but for its capacity to vibrate within a larger whole.

What is remarkable in this body of work is Nicholson’s ability to navigate exuberance with discipline. Her late palette may appear more audacious, but it is grounded in years of refinement and sensitivity. Colours that could easily clash are instead carefully orchestrated to evoke mood, emotion, and spatial depth. Redspossibly rendered in Scarlet Lake or Geranium Lakefloat above cooler substrata of Monestial Blue and Sevres Green, creating compositions that shimmer without ever overwhelming the eye.

In her handwritten shopping list from 1980, we glimpse the depth of her chromatic understanding. This list is not merely utilitarian; it reads like a liturgical chant of pigment: Crimson Lake, Cobalt Pale, Magenta, Vermillion, three shades of Cobalt Violet. For Nicholson, each pigment had a specific tonal identity, and each manufacturer offered a variation that could tip the balance of a composition. Her not, e“I want the makers that I list – the colours are different in the different makers,” demonstrates a hyper-attuned sensitivity to nuance that borders on musical precision. Her pigment choices were not incidental; they were deliberate instruments in her symphony of light.

The painting Prismatic Five exemplifies this complexity. Here, brilliant notes of Cadmium Yellow Deep and Cobalt Blue collide and harmonize with the deeper resonance of Cobalt Violet. These high chromatic voices are grounded by earthy undertonessubtle neutrals mixed from Raw Umber, Zinc White, and Yellow Ochre that stabilize the composition like a gentle bass line. It is in this equilibrium of bold and soft, radiant and restrained, that Nicholson's genius quietly asserts itself. She allows colour to shine, but never permits it to overwhelm.

Her brushwork, too, becomes more expressive in these late,r simultaneously spontaneous and controlled. Passages of impasto give her canvases a palpable texture, while glazes and scumbles create moments of whisper-soft translucency. These layered gestures lend the rainbows a physicality, a presence that transcends illusion. It’s as though each painting were both a vision and an artifact echo of inner seeing made visible.

Painting as Illumination: Colour as Metaphysics in Nicholson’s Final Flourish

Beyond their visual radiance, the Prismatic Paintings pulse with spiritual intensity. For Nicholson, colour was not simply a visual delight or compositional strategy had become a sacred medium. Through correspondence with Glen Schaefer, it becomes evident that she believed colour to be the earthly residue of a divine energy terrestrial manifestation of a universal light. Her paintings thus became meditations, visual mantras through which viewers could glimpse a transcendence that defied literal representation.

Her fascination with perceptionlight refracted, colour dispersedmerged seamlessly with a growing interest in metaphysics. These were not abstract experiments for abstraction’s sake. They were grounded in the reality of paint, the tactility of canvas, the sensory delight of pigment. Yet they reached beyond the eye, beckoning viewers into a space where form dissolves into feeling, and hue into vibration.

Despite their apparent departure from earlier works, these paintings do not abandon the pastthey absorb and recontextualize it. The soft lemon of Cyclamen and Primula, the vivid reds of Flowers On A Windowsill, the dusky indigos of Easter Mondayall reappear in fragmented, refracted form. Her career is not a collection of isolated stages, but a continuum culminating in this final effusion of light and feeling. Each painting is a summation, a prismatic recollection of everything that came before.

In her eighties, Nicholson painted with a fervour that defied expectation. There is an urgency in these works, a sense of joyous culmination. No longer content to record the world as seen, she sought to reimagine itto transmute the seen into the felt, the ordinary into the divine. Colour, for her, was no longer anchored to the surface. It hovered, floated, whispered across the canvas, echoing the music of existence itself.

There is an intimacy in the Prismatic Paintings that extends an invitation. They do not dictate interpretation but create a field in which viewers might find their own revelations. The absence of narrative, the dissolution of form do not signal detachment but generosity. Nicholson leaves space for us, the viewers, to enter and be transformed. Each painting is less a conclusion than an opening, a window onto a vision that continues to expand long after the eye has looked away.

As we retrace her chromatic evolution from the tentative geometries of Cyclamen and Primula, through the contemplative blooms of Flowers On A Windowsill, into the still-spun light of Easter Monday, and finally the ecstatic radiance of the Prismatic Paintings, witness an artist in constant dialogue with her medium. She did not just see colour; she heard it, breathed it, believed in it. Her palette was more than a painter’s toolit was a pathway, a question, and ultimately, a profound answer.

Winifred Nicholson’s legacy lies not only in the visual beauty of her work but in the invitation it offers: to look again, more deeply; to feel colour not as ornament, but as truth. In the luminous crescendo of her final works, we encounter not just the culmination of a lifetime’s practice, but a vision that continues to shimmer at the edge of perceptionendlessly refracting, endlessly renewing.