In photography, asymmetry can create a dynamic and engaging visual experience, challenging viewers to explore the frame beyond the center. Unlike symmetrical compositions, which often evoke calmness and stability, asymmetry introduces tension that can make an image feel alive. By deliberately positioning elements unevenly, photographers invite the eye to travel across the scene, discovering subtle interactions between subjects.

One way to observe this concept in practice is through Southwest desert scenery collection, where the natural formations themselves rarely follow uniform patterns. These pieces demonstrate how irregularity can establish focal points that command attention, showing the power of asymmetry to convey narrative without perfect balance.

The Psychology Behind Visual Tension

Tension in photography isn’t accidental—it’s a psychological tool that guides perception. Viewers subconsciously recognize that imbalance creates movement, prompting them to search for relationships between elements. For example, an oil painting can utilize tonal contrasts and uneven spatial arrangements to mimic this sensation, much like Stuart Davies journey from commercial art demonstrates the evolution from structured design to expressive tonal play. The tension generated by asymmetry stimulates curiosity, keeping the audience engaged longer than perfectly balanced scenes.

Visual tension is a fundamental concept in art and design, shaping how viewers perceive and emotionally respond to an image or composition. It occurs when elements within a visual space appear unsettled, dynamic, or in contrast, prompting the eye and mind to actively engage with the work. Unlike balance, which conveys stability and calm, visual tension introduces energy, anticipation, and emotional impact. Understanding the psychology behind visual tension allows artists, designers, and photographers to create work that captures attention, evokes emotion, and communicates meaning more effectively.

Color Interaction in Asymmetric Compositions

Color is a vital tool for managing asymmetry in photography. When hues are placed unevenly, they can draw attention to specific areas, amplifying the sense of imbalance while still maintaining cohesion. For instance, knowing how different paints interact can help photographers and artists alike, a principle explored in choosing the right acrylic paints. These insights are crucial for understanding how visual tension can be controlled with subtle shifts in tone, guiding the eye across the frame even when the composition feels intentionally unsettled.

At its core, visual tension is rooted in human perception. Our brains are naturally wired to seek order and predictability; we instinctively look for patterns, symmetry, and familiar structures. When these expectations are disrupted, the brain experiences a subtle “cognitive pull,” an urge to resolve uncertainty. This response explains why asymmetry, contrast, and unexpected juxtapositions create visual tension—they challenge our perceptual expectations and demand mental engagement. For example, a tilted horizon line in a photograph or a figure placed off-center generates a mild sense of imbalance, prompting viewers to explore the image more thoroughly. The tension arises not from disorder itself, but from our brain’s desire to make sense of it.

Spatial Dynamics and the Rule of Thirds

While asymmetry may seem random, successful compositions rely on underlying spatial rules. The rule of thirds, for example, divides a frame into nine segments, providing an invisible grid that allows elements to be offset deliberately. Spa settings often use this principle in design, which can inspire photographic compositions. Observing spa and resort interior collection highlights how asymmetrical arrangements can evoke serenity without relying on symmetry, showing that tension and balance are not mutually exclusive but complementary forces in visual storytelling.

Color, contrast, and scale also play a critical role in eliciting visual tension. Bold color contrasts, stark lighting differences, and dramatic size variations create a sense of urgency and focus, guiding attention while generating emotional response. Similarly, overlapping shapes, intersecting lines, or crowded versus empty spaces contribute to tension by creating visual friction. These elements manipulate both perception and emotion, influencing how viewers interpret and react to a composition. Tension is not inherently negative; rather, it adds depth and dynamism, making an image more compelling and memorable.

Balancing Classical Principles with Modern Creativity

Classical art often emphasizes symmetry, yet many modern interpretations embrace asymmetry to inject life into compositions. By studying classical and neoclassical painting series, photographers can learn to juxtapose traditional balance with uneven visual weight. This interplay allows viewers to experience both familiarity and surprise, demonstrating how asymmetry, when grounded in classical principles, enhances visual appeal while preserving coherence.

Psychologically, visual tension can evoke a wide range of emotions depending on context. In art, it may create excitement, anxiety, anticipation, or intrigue. In advertising and design, tension captures attention and motivates action by breaking visual monotony. In photography, it can heighten narrative impact, emphasizing movement, conflict, or emotional intensity. Essentially, tension functions as a bridge between the visual stimulus and the viewer’s emotional experience, enhancing engagement and ensuring the work leaves a lasting impression.

Motion and Energy in Asymmetric Photography

Dynamic compositions frequently rely on implied movement, with asymmetry enhancing the sensation of energy. Sports photography offers excellent examples, where the unpredictable nature of motion results in naturally unbalanced yet captivating images. For insight into how energy is captured visually, sports photography collection illustrates how imbalance can amplify drama. Photographers can borrow these strategies to create tension that feels alive, as if the scene is perpetually unfolding before the viewer’s eyes.

Importantly, effective use of visual tension requires balance. Too little tension results in predictability and boredom, while too much can overwhelm or confuse the viewer. Skilled artists and designers use tension strategically, carefully orchestrating visual elements to create a sense of unresolved energy while maintaining coherence. Negative space, proportion, and directional lines often serve as counterweights, allowing tension to exist without descending into chaos.

Medium Choice and Its Effect on Perception

The medium used to create a visual work can greatly affect how asymmetry is perceived. Oil, acrylic, and monochrome approaches each introduce unique textures and tonal variations that interact differently with imbalance. For instance, exploring Cobra oil paint review reveals how certain paint types can be manipulated to emphasize focal points without requiring perfect symmetry. These insights can guide photographers in translating painterly principles into photographic practice, particularly when experimenting with light, shadow, and perspective.

By understanding how the human brain responds to imbalance, contrast, and disruption, creators can harness tension to engage viewers, provoke thought, and convey meaning. Visual tension is not simply a compositional technique—it is a psychological tool that transforms static images into dynamic experiences. Whether in photography, design, or fine art, mastering the use of tension allows artists to create work that captivates the eye, stirs the mind, and resonates on a deep emotional level, demonstrating the profound connection between human psychology and visual expression.

Minimalism and Monochromatic Tension

Reducing color and complexity can make asymmetry even more striking. Monochrome compositions rely entirely on shape, contrast, and spatial arrangement to create tension. Analyzing one color art collection demonstrates that even subtle variations in tone or form can sustain interest in a seemingly simple frame. For photographers, this teaches the value of restraint, showing that asymmetry doesn’t require chaos—carefully curated minimal elements can achieve a profound sense of balance through tension.

Minimalism in art and photography is often associated with simplicity, calm, and clarity, yet when combined with monochromatic design, it can create a subtle but powerful sense of tension. By stripping away unnecessary elements and reducing the palette to a single color or tonal range, artists force the viewer to focus on composition, form, and the interplay of light and shadow. This tension emerges not from clutter, but from the careful arrangement of minimal elements within a restricted visual space. In essence, less becomes more—but with an intensity that captures attention and evokes emotion.

Emotional Resonance Through Asymmetric Framing

Asymmetry often evokes stronger emotional responses than rigid symmetry because it mirrors real-world imperfections. Even small, seemingly random details can convey narrative or mood. Observing artworks such as black and pink abstract collection demonstrates how color placement and uneven shapes generate a sense of drama and intimacy. For photographers, understanding how to harness this emotional resonance through asymmetrical framing allows the creation of images that connect deeply with audiences.

Monochromatic compositions rely on variations in tone, contrast, and texture to generate depth and interest. Even a single color can convey energy or unease when juxtaposed with strong geometric shapes, diagonal lines, or asymmetrical placement. For example, a lone object positioned off-center in a muted frame can create visual tension, prompting the viewer’s eye to explore the negative space and anticipate resolution. The tension is subtle yet compelling, demonstrating how simplicity can heighten perception rather than diminish it.

Integrating Wildlife and Nature into Uneven Compositions

Natural subjects, including animals, inherently resist symmetrical placement, offering perfect opportunities to explore asymmetry. For example, wildlife photography often benefits from off-center positioning, creating tension and guiding attention across the scene. The subtle use of composition strategies can be observed in raccoon photography collection, where placement of the subject against a dynamic background establishes balance without mirroring. Such techniques highlight that successful asymmetry balances deliberate design with organic unpredictability, producing images that feel both intentional and alive.

Minimalism and monochromatic tension work together to engage viewers psychologically. The lack of distraction focuses attention on relationships between elements, amplifying the emotional and conceptual impact. Shadows, gradients, and empty space become as meaningful as the objects themselves, turning minimal compositions into rich, thought-provoking experiences. This approach challenges traditional expectations of color and complexity, proving that tension does not require abundance—it thrives in restraint.

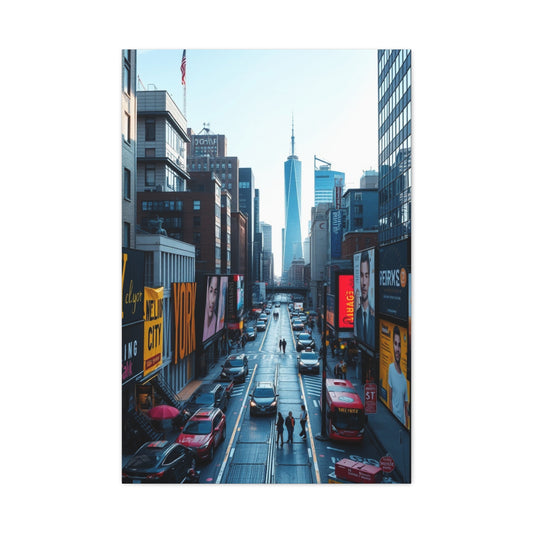

Urban Scenes and Street Photography Tension

Street photography thrives on unpredictability, where asymmetry is inherent in every frame. The dynamic interplay of pedestrians, vehicles, and architectural elements creates natural imbalance that engages the viewer. Studying urban street scene collection provides insight into how seemingly chaotic compositions can be organized visually. Photographers can harness this spontaneous energy by carefully observing lines, forms, and contrasting textures, turning ordinary cityscapes into compelling narratives that feel both chaotic and intentional. Asymmetry in urban imagery draws attention to unique interactions that might otherwise go unnoticed, creating tension that keeps the eye moving across the frame.

Choosing the Right Support for Photography

The tools used to stabilize a camera influence both the technical quality and creative potential of photographs. Tripods and monopods offer distinct advantages depending on the shooting context, whether capturing motion blur, long exposures, or complex compositions. A detailed comparison can be explored in monopod versus tripod guide, which highlights their unique impact on framing asymmetrical compositions. Understanding the subtle differences between support systems helps photographers intentionally design imbalance in their shots while maintaining control, blending technical precision with creative experimentation.

The Emotional Power of Color

Color has a profound psychological influence in photography and painting, particularly when used asymmetrically. Vibrant reds, for example, can dominate a composition and guide viewers’ emotions. Learning about historical pigments, like vermilion, sheds light on how artists manipulate color to create focus and narrative tension. In story of vermilion pigment, the unique intensity and rarity of this red demonstrate how selective use of color can alter the perception of balance. Photographers can apply these principles, strategically placing vivid tones to counterbalance empty or muted spaces, intensifying both tension and harmony.

Impressionist Influence on Composition

Impressionist artists, with their experimental approach to light and form, offer valuable lessons for asymmetric photography. Monet’s work, for instance, often featured off-center focal points, subtle color shifts, and organic movement within the frame. Observing Claude Monet painting series allows photographers to see how deliberate imbalance can evoke emotion, guiding the eye through layers of visual complexity. This approach highlights that asymmetry is not merely a compositional choice but a method of storytelling, transforming static imagery into immersive experiences.

Seasonal and Holiday Motifs in Uneven Design

The charm of seasonal imagery lies in its potential for playful imbalance. Arrangements that include unexpected details, such as whimsical characters or decorative elements, encourage viewers to explore the scene more fully. For example, examining Christmas gnome illustration shows how off-centered elements can generate narrative tension and delight. Photographers can translate this idea by capturing seasonal setups where subjects interact irregularly with their surroundings, creating images that feel natural, lively, and emotionally engaging.

Nature and Asymmetry in Floral Photography

Flowers are naturally asymmetrical, offering rich opportunities to study imbalance and harmony simultaneously. Sunflowers, with their radiating patterns and irregular growth, provide dynamic compositions that lead the eye along unexpected paths. By observing the sunflower image collection, photographers can learn to balance irregular natural forms with strategic negative space. This approach encourages experimentation with framing, depth of field, and perspective, revealing that organic asymmetry can be a powerful tool to create tension while maintaining aesthetic pleasure.

Portraiture and Narrative Depth

Portrait photography relies heavily on subtle asymmetry to convey emotion, character, and story. Slight shifts in posture, gaze, or background placement can create a powerful sense of tension that engages viewers. Insights from mothers depicted by artists show how asymmetry can be used to highlight emotional nuances and relational depth. Photographers can apply these lessons by deliberately positioning subjects off-center or juxtaposing them against irregular backdrops, producing portraits that feel alive and intimate.

Creative Mounting and Presentation Techniques

Beyond the moment of capture, the presentation of an image can amplify its asymmetrical impact. Mounting prints on alternative surfaces, such as foam board, introduces dimensionality and subtle shadow play that enhances visual tension. Exploring mounting prints on foam core offers practical guidance for elevating photographs from flat compositions to layered visual experiences. This technique reinforces that asymmetry is not just a property of the captured image but also of how the final presentation interacts with the viewer’s perception.

Pop Culture and Dynamic Composition

Iconic pop culture imagery often employs asymmetry to create excitement, narrative, and visual rhythm. Pulp fiction imagery, for example, uses off-center characters, dramatic angles, and contrasting spaces to convey tension and energy. Studying pulp fiction image series provides insight into how asymmetry can enhance storytelling in still images. Photographers can incorporate these lessons into their work by experimenting with angles, cropping, and perspective shifts, resulting in images that maintain balance while feeling energetic and unpredictable.

Everyday Objects as Creative Subjects

Even mundane subjects, like cups of coffee, can be arranged to explore asymmetry and narrative. The interplay between irregular shapes, textures, and lighting can transform ordinary objects into compelling compositions. Observing coffee-themed imagery highlights how small, seemingly insignificant adjustments in placement and framing create visual tension. Photographers can use these principles to find art in everyday life, demonstrating that asymmetry is not only a stylistic choice but a way to reveal hidden beauty and nuance in familiar environments.

Trees as Subjects in Asymmetric Photography

Trees provide one of the most natural examples of asymmetry in photography. Each branch, leaf cluster, and trunk twist creates unique tension that guides the eye across the frame. By observing trees and forest imagery collection, photographers can study how uneven growth and irregular spacing become compelling compositional tools. Using trees as focal points encourages a balance between empty space and complex textures, teaching that visual tension can be both structured and organic, a harmony achieved by embracing nature’s inherent imperfection.

Bringing Fine Art Into Everyday Spaces

The method of presenting photographs or reproductions can greatly affect perception. High-quality canvas reproductions elevate ordinary images to museum-quality experiences, emphasizing depth and detail. Learning from museum quality canvas display demonstrates how intentional presentation of artwork can enhance asymmetry and narrative flow. Photographers can apply these lessons by considering not just framing and composition, but also the material and environment in which their images are showcased, adding layers of visual engagement.

Musical Inspiration and Visual Rhythm

Music and photography share an affinity for rhythm and movement, and asymmetry can mirror the dynamic qualities of sound. When compositions incorporate flowing lines, staggered elements, or contrasting forms, they create a visual symphony. Exploring music inspired canvas imagery illustrates how musicality can guide photographic decisions, emphasizing balance through uneven yet deliberate placement. Photographers can study tempo, repetition, and improvisation in music to inform how spatial tension and asymmetry enhance emotional impact in visual art.

Holiday Themes and Asymmetric Arrangements

Festive imagery often relies on playful irregularity to evoke warmth and nostalgia. For example, holiday trees or wreaths positioned off-center can create engaging tension that draws attention to details. Observing Christmas tree and wreath collection shows how deliberate irregularity enhances storytelling. Photographers can translate this into their practice by experimenting with off-balance arrangements in seasonal settings, revealing that asymmetric placement can amplify both charm and narrative clarity.

Nostalgic Elements in Dynamic Composition

Nostalgia in imagery is heightened by visual tension and carefully curated imbalance. Elements that are slightly misaligned or framed unexpectedly can evoke memories more powerfully than strictly centered subjects. Examining 90s nostalgia imagery series demonstrates how composition can engage viewers emotionally, guiding their gaze across elements with uneven distribution. Asymmetry in nostalgic imagery reinforces the connection between memory and perception, showing that tension is often a conduit for emotional resonance.

Tropical Vistas and Irregular Balance

Tropical environments offer vibrant asymmetry through irregular foliage, water reflections, and sunlight patterns. These unpredictable elements can be arranged into cohesive compositions that feel natural and dynamic. Observing tropical imagery collection provides insight into harnessing uneven visual weight while maintaining aesthetic harmony. Photographers can study natural contrasts, such as jagged palm fronds against smooth horizons, to create images that convey both energy and tranquility through asymmetrical balance.

Contemporary Color as a Design Tool

Bold and unconventional color choices enhance asymmetry by guiding attention to off-center subjects or unexpected areas of a frame. Mustard yellow, for instance, can dominate a composition without overwhelming it when strategically positioned. Insights from mustard yellow contemporary reimagined demonstrate how color can act as a visual counterbalance, helping photographers craft dynamic yet cohesive images. Using vibrant hues in uneven patterns reinforces both tension and engagement, adding depth to compositions.

Muted Tones and Subtle Balance

Asymmetry does not always require bright or dramatic elements; muted tones can create subtle, contemplative tension. Daniel Smith’s collaborative grey series, for instance, reveals how restrained palettes can evoke depth and harmony. Exploring muted grey collaborative series offers photographers lessons on using understated elements to guide the eye across irregular compositions. Even in low-contrast environments, uneven distribution of subtle tones maintains visual interest and supports storytelling.

Urban Landscapes and Off-Center Horizons

City skylines naturally lend themselves to asymmetric framing. Skyscrapers, bridges, and urban infrastructure can be arranged off-center to convey movement, depth, and tension. Observing city skyline compositions demonstrates how asymmetry captures energy in static frames. Photographers can experiment with negative space, reflections, and leading lines to highlight irregular architectural patterns, creating images that feel alive and immersive even in structured urban environments.

Circular and Abstract Forms in Composition

Abstract and circular shapes challenge conventional balance, offering opportunities to explore asymmetry in more conceptual ways. Radial forms, spirals, and overlapping circles create tension through non-linear arrangement. Studying circular abstract image series illustrates how geometric irregularity can generate visual rhythm while maintaining harmony. Photographers can integrate abstract compositional strategies into their work by combining organic and geometric forms, producing images that engage viewers intellectually and emotionally through asymmetric design.

Romantic Themes and Asymmetric Design

Romantic compositions often use subtle imbalance to convey intimacy and emotion. Whether in still life or environmental portraiture, off-center arrangements can evoke passion and narrative depth. Studying Valentine’s Day image collection illustrates how irregular placement of symbols, colors, and forms enhances emotional resonance. Photographers can adopt similar strategies by positioning subjects in unexpected ways, allowing tension to highlight the story between elements rather than relying on symmetry to convey affection.

Pop Culture Influence on Visual Tension

Pop-inspired visuals leverage bold colors, unexpected angles, and irregular spacing to create dynamic compositions. Personal experiences with contemporary pop imagery show how playful asymmetry engages viewers while maintaining coherence. Observing pop art fascination collection reveals how contrast, scale, and placement can produce visual tension without chaos. Photographers can apply these lessons to integrate modern vibrancy into their work, balancing spontaneity with compositional clarity.

Folklore and Mythic Spatial Arrangements

Enchanted interiors and folkloric narratives rely on asymmetry to evoke mystery and wonder. Strategic irregularity in placement of objects, patterns, and focal points creates immersive experiences that draw viewers in. Exploring mythic interiors transformation demonstrates how uneven visual weight can enhance storytelling. For photographers, adopting similar principles means arranging subjects to guide the eye naturally while creating narrative depth through unexpected juxtapositions.

Animal Subjects and Compositional Energy

Animals, with their natural unpredictability, are ideal subjects for asymmetric compositions. Black cats, for instance, offer striking contrasts when placed off-center against diverse backgrounds. Studying black cat imagery refined collection reveals how subtle variations in posture and environment can generate tension. Photographers can capture these moments by embracing uneven spacing, negative space, and contrast, producing images that feel both dynamic and intimate.

Dual Perspectives on Similar Subjects

Examining similar subjects from multiple angles emphasizes how small shifts in composition affect perception. Another interpretation of black cat imagery, seen in black cat gallery collection, demonstrates that even minor repositioning can dramatically change the narrative and tension of a frame. This approach encourages photographers to experiment with perspective and placement, revealing that asymmetry can be explored infinitely within the same subject.

Vintage and Historical Compositional Lessons

Vintage imagery teaches the power of visual irregularity and narrative depth. Older compositions often employ off-center focal points, layered textures, and irregular framing to evoke authenticity and nostalgia. Observing vintage imagery collection highlights techniques that contemporary photographers can repurpose, balancing modern clarity with historical charm. By studying these examples, one learns how asymmetry is not merely a stylistic choice but a storytelling tool rooted in centuries of artistic practice.

Mythology as a Guide for Visual Storytelling

Ancient stories, when visualized, benefit from asymmetric arrangement to highlight tension, conflict, and movement. Mythological scenes often depict overlapping figures and off-balance landscapes to draw the eye across the narrative. Insights from mythology and folklore imagery show how narrative flow can be achieved through uneven placement, guiding the viewer’s gaze and creating layered meaning. Photographers can translate these lessons by arranging subjects dynamically, emphasizing interaction and motion within a frame.

Texture and Material in Asymmetric Design

The choice of surface or material can enhance the perception of tension in photography. Textured backgrounds, such as grasscloth, add subtle depth that interacts with composition. Exploring grasscloth beginner guide demonstrates how materiality influences the perception of imbalance, allowing photographers to experiment with tactile contrasts and layering. Using uneven textures reinforces asymmetry, creating images that feel rich and immersive even in minimalistic setups.

Aquatic Life and Dynamic Framing

Marine subjects provide natural irregularity, with movement, light refraction, and spatial unpredictability shaping composition. Studying stingray imagery gallery illustrates how the interplay of motion, negative space, and off-center positioning creates tension and visual intrigue. Photographers can capture the fluidity and unpredictability of aquatic life, translating natural asymmetry into dynamic, expressive images that balance energy and visual harmony.

Music and Rhythm in Photography

Music-themed imagery often relies on asymmetry to express rhythm, movement, and emotional depth. Placement of instruments, musicians, or abstract musical forms can guide the viewer through a visual performance. Observing R&B inspired image series demonstrates how irregular spacing and layered elements evoke sound and emotion. Photographers can apply these principles to create compositions that feel musical and alive, emphasizing flow, tension, and visual storytelling through asymmetric design.

Ocean Waves and Fluid Composition

The movement of waves provides a natural example of asymmetry in photography. Each crest, ripple, and reflection creates dynamic tension that guides the viewer’s eye unpredictably. Observing wave photography collection offers insight into how irregular shapes and rhythmic flow can be used to create a sense of motion and balance simultaneously. Photographers can use the shifting energy of water to experiment with off-center framing and varying focal points, showing that natural asymmetry can evoke both serenity and excitement in a single image.

Organizing Tools for Creative Photography

Maintaining an organized workspace is essential for creative output, especially when juggling multiple media and equipment. Tools like specialized brush and pencil rolls can streamline workflow while keeping essential items accessible. Exploring Blake brush and pencil roll provides practical strategies for photographers and artists to manage their tools efficiently. A well-organized setup encourages experimentation, allowing for more deliberate asymmetric compositions and reducing distraction from the creative process.

Mastering Overhead and Flat Lay Shots

Flat lay photography emphasizes the strategic arrangement of elements on a horizontal plane, where asymmetry plays a critical role in guiding the viewer’s eye. By deliberately offsetting subjects and layering objects, photographers can create balance within apparent irregularity. Studying overhead styling techniques shows how careful composition can transform a simple arrangement into a visually compelling scene. This method highlights that asymmetry is not accidental; it is a carefully controlled tool to evoke rhythm, tension, and narrative in still imagery.

Jazz and Musical Influences in Visual Art

Music has a profound ability to inspire visual compositions, and jazz in particular demonstrates improvisational asymmetry. Billie Holiday-inspired imagery captures emotion, movement, and energy through off-centered focal points and layered elements. Observing Billie Holiday image collection provides insight into how musical rhythm can inform visual tension. Photographers can translate these concepts by incorporating uneven spacing, contrast, and tonal variation to produce images that resonate emotionally and dynamically with viewers.

Classical Instruments and Dynamic Framing

Musical instruments, like violins, offer unique opportunities for asymmetric composition due to their elegant curves and intricate details. Off-center positioning against contrasting backgrounds emphasizes shape, shadow, and texture. Exploring elite violin image series demonstrates how photographers can highlight form through strategic imbalance. Integrating these techniques into broader compositions allows for the creation of images that balance aesthetic appeal with narrative and emotional resonance.

Western Themes and Natural Imbalance

Western landscapes, with their vast horizons, rugged terrain, and irregular architectural forms, are ideal for exploring asymmetry. Elements like fences, horses, and barns can be positioned off-center to create tension and guide the eye. The Western collection of imagery shows how photographers can balance expansive negative space with focal points, producing scenes that feel dynamic yet cohesive. This approach demonstrates that asymmetry can enhance storytelling by emphasizing environmental context alongside subject placement.

Efficient Workflow in Post-Processing

Technical skill in editing can enhance the compositional impact of asymmetrical photographs. Using tools like Lightroom to streamline adjustments ensures that visual tension and focal emphasis are maintained consistently. Exploring optimizing Lightroom workflow provides techniques to enhance color, contrast, and alignment while preserving natural irregularity. Photographers can refine asymmetrical compositions in post-production without erasing the spontaneity and energy that make them compelling.

Monochromatic Design and Visual Harmony

Single-color palettes can create striking asymmetry by emphasizing form, shadow, and texture without relying on multiple hues. Monochromatic design allows photographers to focus on spatial relationships and balance within irregular compositions. Observing monochromatic style guide demonstrates how the careful arrangement of shapes, lines, and negative space generates visual interest even when color variety is minimal. This approach highlights that asymmetry relies on more than color; it is deeply tied to shape, proportion, and contrast.

Geometric Compositions and Square Arrangements

Geometric shapes, particularly squares and rectangles, provide opportunities to explore asymmetric balance within a defined framework. Off-center placement, layering, and rotation of shapes create dynamic tension that engages the viewer. Studying square composition collection shows how structured forms can coexist with irregular arrangements to produce visually stimulating imagery. Photographers can incorporate geometric elements into natural or staged settings, creating a harmonious tension that bridges order and spontaneity.

Vaporwave and Contemporary Abstract Influence

Vaporwave and other contemporary abstract aesthetics emphasize surreal compositions and irregular forms, challenging conventional balance. The use of unusual perspectives, color shifts, and layered motifs creates tension and intrigue. Observing Warakami vaporwave collection provides insight into how modern visual language can leverage asymmetry to captivate viewers. Photographers can experiment with color, shape, and layering in imaginative ways, demonstrating that tension and balance are not opposites but complementary tools in contemporary visual storytelling.

Conclusion

Photography is not just about capturing reality—it is about shaping perception, guiding the viewer’s eye, and evoking emotion. One of the most powerful tools photographers have for achieving this is asymmetry. Unlike symmetrical compositions, which convey stability and calm, asymmetry introduces tension, energy, and dynamism. It challenges traditional notions of balance while still allowing for visual harmony, creating images that are engaging, memorable, and emotionally resonant. Exploring asymmetry in photography opens up a world of creative possibilities, allowing artists to manipulate visual weight, guide attention, and tell stories in subtle but impactful ways.

Asymmetry in photography is about more than placing a subject off-center; it is about understanding visual weight and how elements interact within the frame. A photograph achieves balance when the distribution of visual interest feels intentional, even if the composition is not mirrored. For instance, a lone figure on one side of an image can be counterbalanced by a cluster of smaller elements, negative space, or contrasting textures on the opposite side. This creates a sense of tension that engages viewers, inviting them to explore the photograph and discover its nuanced details. Asymmetry encourages the eye to move around the frame rather than settling immediately, enhancing the storytelling potential of the image.

Tension created by asymmetry is a key factor in its appeal. By deliberately avoiding perfect symmetry, photographers can evoke emotions such as curiosity, unease, or anticipation. This tension is often subtle yet powerful, compelling viewers to interact mentally with the image and consider the relationships between its elements. Asymmetrical compositions are particularly effective in dynamic or narrative photography, where movement, contrast, or unexpected juxtapositions can heighten the impact. By embracing imbalance strategically, photographers can transform ordinary scenes into visually compelling experiences that linger in the viewer’s mind.

Despite its inherent tension, asymmetry does not mean chaos. Successful asymmetrical photography relies on achieving a sense of visual equilibrium. Lines, shapes, color contrasts, and negative space can all serve as tools to balance an otherwise unbalanced composition. The goal is not to create randomness but to orchestrate elements so that they feel harmoniously arranged, even as they disrupt conventional expectations. Understanding how to leverage contrast, spacing, and proportion allows photographers to maintain coherence while exploring creative freedom.

In conclusion, exploring asymmetry in photography is a journey into the interplay between tension and balance. By thoughtfully arranging elements, leveraging negative space, and manipulating visual weight, photographers can create images that are both dynamic and harmonious. Asymmetry invites viewers to engage more deeply, provoking emotion and encouraging exploration within the frame. It challenges traditional notions of beauty and order, proving that balance does not require symmetry. Ultimately, asymmetry enriches photographic storytelling, offering endless opportunities to capture moments with energy, depth, and visual intrigue. For photographers seeking to elevate their work, embracing asymmetry is not just a compositional choice—it is a creative philosophy that transforms images from mere documentation into compelling visual art.