Leonardo da Vinci's works continue to mesmerize the world centuries after they were created, capturing both the technical mastery and the philosophical depth that defined the Renaissance. His paintings are more than just images; they are explorations of human emotion, nature, and the interplay of light and shadow. The Mona Lisa, for instance, is widely celebrated not only for its enigmatic smile but also for its revolutionary approach to portraiture. Many modern collectors and enthusiasts look for ways to incorporate similar aesthetic elegance into their personal spaces. One way to bring a sense of refined taste into your home is through grey inspired decor ideas, which subtly echoes the balance and compositional mastery seen in da Vinci's works. The muted tones and intricate textures of grey artworks can evoke the quiet introspection often felt when observing da Vinci’s masterpieces, creating a contemplative atmosphere that bridges the centuries.

The Mona Lisa and Emotional Resonance

The Mona Lisa represents a pinnacle of artistic innovation, particularly in the way it captures psychological depth through subtle facial expression. Da Vinci's use of sfumato—a technique that allows tones and colors to blend seamlessly—is key to this effect. The painting's enduring appeal lies in the subtle interplay between realism and mystery. Translating this concept into contemporary decor, one can look for ways to transform your hallway with unique creative ideas for hallway decor that engage viewers similarly. Strategic placement of art in everyday spaces can stimulate the mind, invite reflection, and make even a simple hallway an arena for aesthetic discovery. Much like da Vinci’s layering of light and shadow, thoughtful arrangement of modern artworks can create depth and intrigue in ways that parallel Renaissance techniques.

The Last Supper and Narrative Complexity

The Last Supper is a masterclass in storytelling through composition, using perspective to draw viewers directly into the scene. Each figure conveys emotion and purpose, and the interactions among the apostles reveal da Vinci’s unparalleled understanding of human psychology. Today, artists and photographers study such complexity to enhance narrative depth in their work. Tools and resources like mastering iPhone photography beginner’s guide allow even novices to explore narrative composition, lighting, and focus in ways reminiscent of Renaissance approaches. By understanding how da Vinci conveyed emotion through posture and gaze, contemporary visual artists can capture nuanced human expression, even in digital mediums, echoing the timeless lessons of classical painting.

Vitruvian Man and Human Proportions

Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man illustrates his fascination with proportion, symmetry, and the mathematical underpinnings of natural forms. This drawing bridges art, anatomy, and geometry, demonstrating that beauty and precision often go hand in hand. Collectors and enthusiasts today often seek pieces that reflect this harmony between structure and aesthetic appeal. Works such as gastronomic elegance canvas bring balance and elegance into living spaces, echoing da Vinci’s meticulous attention to detail. Each brushstroke, line, or texture contributes to a cohesive whole, emphasizing how thoughtful design can transform everyday environments into spaces that celebrate form, proportion, and visual sophistication.

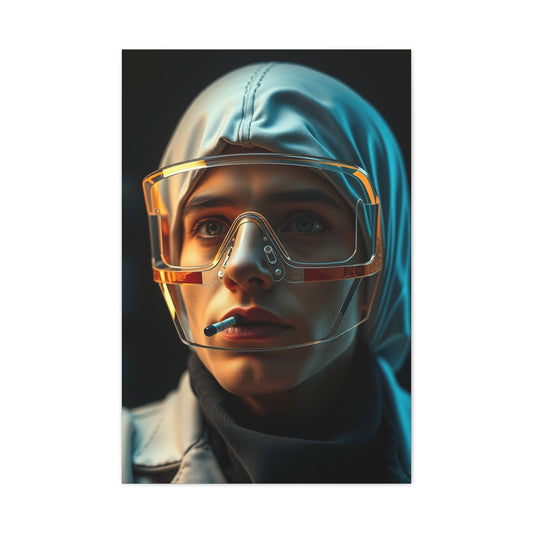

Saint John the Baptist and Mysterious Atmosphere

Saint John the Baptist showcases da Vinci’s mastery of chiaroscuro, where dramatic contrasts between light and shadow create a sense of mystery. The figure emerges from darkness as if suspended between worlds, eliciting both curiosity and reverence from the viewer. Modern interior art enthusiasts can replicate this effect through carefully chosen pieces that emphasize contrast and mood. Selecting artwork like empyrean reverie art allows a space to evoke the same enigmatic aura, guiding observers toward introspection and emotional engagement. Just as da Vinci used shadow to animate form, contemporary art can use tonal variation to cultivate atmosphere and captivate attention, blending historical inspiration with modern expression.

Ginevra de’ Benci and Subtle Expression

Ginevra de’ Benci is a portrait that exemplifies Leonardo’s ability to convey character and intellect through subtle gestures and expressions. Unlike the overt drama of some of his other works, this painting demonstrates restraint and refinement, teaching the importance of nuance. Collectors seeking to emulate this understated sophistication might explore elegant horses decor ideas, which captures movement, grace, and quiet strength. Just as Leonardo focused on fine details and emotional undertones, modern decorative art can bring elegance without overwhelming a room, proving that subtlety often resonates more deeply than extravagance in both human expression and design.

Annunciation and Spatial Innovation

Leonardo’s Annunciation reflects his groundbreaking exploration of spatial perspective, with each figure meticulously placed to convey depth and focus. This innovative approach has influenced countless artists and photographers, encouraging attention to spatial relationships in every composition. Understanding these principles is crucial for modern creators, and resources like top rugged camera cases 2025 guide help contemporary photographers and artists protect their tools as they explore complex setups. By valuing both technical mastery and creative vision, one can replicate the precision and storytelling depth of Renaissance masters in today’s artistic endeavors, whether in photography, painting, or digital media.

Adoration of the Magi and Layered Symbolism

The Adoration of the Magi, though unfinished, reveals da Vinci’s genius in layering symbolism, narrative, and character interaction. Each detail, from gestures to background architecture, contributes to the painting’s richness and interpretive depth. Modern visual enthusiasts can draw inspiration from this approach by curating collections that offer layers of meaning. For instance, top social media platforms for photographers 2025 provide opportunities to share visual storytelling, engage audiences, and explore symbolic depth digitally. The key lesson from da Vinci is that even small details, when thoughtfully considered, can amplify the impact of a work and invite repeated examination, much like the infinite discoveries found in Renaissance masterpieces.

Madonna of the Rocks and Natural Harmony

Madonna of the Rocks demonstrates Leonardo’s integration of natural elements into his compositions, achieving harmony between figures and environment. The interplay of light, texture, and organic forms creates a sense of serene cohesion. Contemporary collectors can echo this principle through artwork that emphasizes balance with nature, such as collection skulls art, where intricate designs mirror natural complexity. By studying how Leonardo balanced foreground and background, artists can cultivate visual equilibrium, ensuring that every element contributes to the overall harmony. This approach reinforces the timeless notion that observing nature and human form together yields the most profound aesthetic experiences.

The Baptism of Christ and Collaborative Influence

Leonardo’s early work on The Baptism of Christ, created in collaboration with his master Verrocchio, showcases the interplay of influence, mentorship, and personal growth. This piece underscores the importance of learning from others while developing one’s unique artistic voice. For modern art collectors, pieces like masterpiece zenja gammer art vision echo a similar narrative of innovation and inspiration. By examining da Vinci’s evolution from apprentice to master, contemporary creators and enthusiasts are reminded that collaboration, study, and experimentation are vital for cultivating skill, vision, and originality, ultimately producing works that resonate across generations.

Leonardo’s Italian Roots and Cultural Influence

Leonardo da Vinci’s artistry was profoundly shaped by his Italian heritage, where cities like Florence and Milan fostered an environment ripe for innovation and exploration. His work embodies the harmony, elegance, and technical brilliance that define Renaissance Italy. For modern admirers seeking to channel this sense of cultural richness, one can explore Italy inspired decor ideas, which celebrates the beauty of Italian landscapes, architecture, and classical charm. Incorporating such visual elements into a personal space allows for daily inspiration, echoing Leonardo’s deep connection to his homeland and the vibrant artistic communities that nurtured his genius.

The Mona Lisa and Modern Living Aesthetics

The Mona Lisa’s subtle expression and enigmatic smile continue to captivate audiences, teaching the power of understated emotion in visual storytelling. The painting’s influence extends beyond galleries into the way spaces are curated, emphasizing balance, contrast, and focus. For example, interiors inspired by art can achieve a similar sense of timeless elegance, much like in modern living rooms with 70s soul, where eclectic pieces merge comfort with style. By thoughtfully integrating art and decor, one can evoke layered narratives, offering visual and emotional engagement similar to the contemplative experience of studying Leonardo’s masterpieces.

The Last Supper and Spatial Storytelling

The Last Supper exemplifies Leonardo’s skill in guiding viewers through a scene using perspective, composition, and gesture. Every element contributes to a cohesive narrative that is both dramatic and intimate. Contemporary spaces can capture this principle by designing interiors that emphasize visual flow and storytelling. One way to achieve this is through stylish loft design ideas, which focus on open layouts, layered textures, and dynamic focal points. By thinking of interiors as a canvas, just like Leonardo did, one can create an environment where movement, light, and form harmonize, offering a sensory experience that mirrors the narrative power of classical painting.

Vitruvian Man and Proportional Harmony

Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man remains a testament to his fascination with human anatomy and mathematical precision. The drawing illustrates how proportion governs both natural and artistic beauty, a concept relevant not only in painting but in modern design. Translating this understanding into contemporary settings, collectors can explore works like elite zebra art vision to introduce patterns and symmetry that echo the balance Leonardo championed. This approach emphasizes that thoughtful observation and structural integrity can elevate the aesthetic experience, reminding us that design, like art, benefits from harmony between detail and overall composition.

Saint John the Baptist and the Play of Shadow

The dramatic chiaroscuro of Saint John the Baptist demonstrates Leonardo’s mastery of light and shadow to evoke mood and presence. The use of darkness surrounding the figure heightens tension and focuses attention, offering lessons in the emotional power of contrast. Contemporary interiors can draw inspiration from this technique by incorporating luxe paschal impressions, where dramatic elements interplay with softer tones, creating depth and intrigue. By applying these principles, modern spaces can achieve an evocative ambiance, illustrating how lessons from Renaissance painting remain relevant in shaping perception and emotional engagement.

Ginevra de’ Benci and Subtle Character Study

Ginevra de’ Benci exemplifies Leonardo’s ability to reveal personality through delicate detail. Every line, shadow, and gesture conveys intellect and subtle emotion. Contemporary viewers can experience a similar appreciation for nuance by integrating art with understated sophistication. Collections like Jesus inspired decor ideas can provide narrative and spiritual resonance, drawing attention to subtleties in posture, expression, and context. Leonardo’s work reminds us that true mastery lies in attentiveness to the understated, where even the smallest visual cues communicate depth and character.

Annunciation and Light-Filled Composition

Annunciation highlights Leonardo’s exploration of spatial depth and naturalistic lighting, where composition guides viewers’ eyes through the scene. The painting is a study in directing focus without overwhelming complexity. Modern design can reflect this principle in functional yet visually engaging spaces. For instance, modern kitchen renovation inspiration encourages the use of light, color, and layout to create harmony, illustrating how composition in living spaces parallels principles seen in classical painting. Thoughtful use of perspective and illumination transforms ordinary spaces into immersive visual experiences, echoing Leonardo’s attention to spatial storytelling.

Adoration of the Magi and Narrative Layers

The unfinished Adoration of the Magi reveals Leonardo’s ability to layer meaning and create complexity within a composition. Each figure, gesture, and element contributes to a rich narrative that rewards careful observation. Modern interior design can similarly embrace layers, using pieces like transform the space under your stairs to maximize utility while adding visual interest. The principle remains the same: detail and planning enhance engagement, whether in painting or in the way a space is curated, encouraging continuous exploration and interaction from the audience or inhabitant.

Madonna of the Rocks and Environmental Integration

Madonna of the Rocks demonstrates Leonardo’s sensitivity to integrating figures within natural landscapes, creating harmony between human presence and environment. Contemporary curators can replicate this balance by selecting works that complement and interact with their surroundings. Pieces like eminent masculine decor ideas introduce textures, tones, and forms that resonate with natural or architectural features, achieving a sense of cohesion and visual rhythm. Leonardo’s mastery teaches that thoughtful integration enhances aesthetic impact, transforming spaces into environments that feel both intentional and alive.

The Baptism of Christ and Early Mastery

Leonardo’s contribution to The Baptism of Christ showcases his early skill and the influence of mentorship in shaping artistic vision. The collaborative process emphasizes learning, adaptation, and the evolution of personal style. Contemporary audiences can draw parallels in cultivating creativity, exploring pieces like luxe Parisian reverie to bring sophistication, elegance, and narrative depth into modern spaces. The painting serves as a reminder that mastery is a journey, nurtured by observation, experimentation, and dedication, reflecting a timeless lesson for artists and collectors alike.

Leonardo’s Influence on Domestic Spaces

Leonardo da Vinci’s art is renowned not only for technical mastery but for its ability to elevate everyday perception, inspiring viewers to notice balance, symmetry, and intricate detail. His compositions, whether in portraiture or religious scenes, often create a sense of harmony that resonates beyond the canvas. In contemporary interiors, this philosophy can be reflected in functional yet beautiful spaces. For instance, incorporating kitchen decor ideas collection brings a dynamic and visually stimulating element to spaces often overlooked, reminding us that even utilitarian areas can carry elegance, refinement, and inspiration akin to da Vinci’s artistry.

The Colorful Genius of Leonardo

While Leonardo is known for subtle tonal mastery, his study of pigments and careful layering of color laid the foundation for emotional resonance in painting. His approach underscores the significance of intentional color selection, as every shade contributes to mood and depth. Modern enthusiasts can explore colorful world of inscribe soft pastels to experiment with tonal variation, texture, and layering techniques. Just as Leonardo experimented with sfumato to soften transitions, contemporary creatives can harness color subtly to evoke feeling, movement, and narrative, bridging centuries of artistic inquiry through hands-on exploration.

Nature and Observation in Leonardo’s Work

Leonardo’s fascination with the natural world is evident in sketches of flora, fauna, and anatomical studies. Observation and documentation of the environment informed his art, infusing it with lifelike vitality. Today, artists and collectors draw inspiration from detailed representations of nature. Examining collections such as natalie mcintyre insect drawings reminds us that meticulous attention to detail can reveal beauty in the most minute aspects of life. Leonardo’s practice teaches that careful observation fosters insight, allowing both art and life to be enriched through patient study of the natural world.

Urban and Architectural Influence

Leonardo’s time in Italian cities exposed him to architectural grandeur, urban planning, and public spectacle, influencing his compositions and sense of spatial order. This connection between human-made structures and art can be mirrored in contemporary urban-inspired aesthetics. Modern collectors can incorporate views and panoramas reminiscent of cityscapes, such as luxe miami panorama masterpiece, to bring energy, scale, and structural elegance into personal spaces. These visual cues echo Leonardo’s fascination with perspective, proportion, and the interrelation of figures within architectural frameworks.

Luminous Techniques and Emotional Depth

Leonardo’s ability to manipulate light creates depth and emphasizes emotional subtlety, transforming portraits into living, breathing narratives. This manipulation of luminosity can be translated into contemporary visual mediums, where light and reflection enhance atmosphere and perception. Integrating pieces like luminous elegance canvas allows modern spaces to embody a sense of depth and emotional resonance, echoing the immersive quality of da Vinci’s paintings. The subtlety of light and shade teaches that observation and intention are crucial, whether on canvas or in the arrangement of a living environment.

Symbolism and Animal Imagery

Leonardo frequently incorporated animals as symbolic devices, demonstrating his understanding of both natural behavior and allegorical significance. From lions representing courage to birds symbolizing freedom, these elements enrich narrative and invite reflection. Contemporary collections, such as lion inspired decor ideas, offer similar inspiration by blending aesthetic impact with symbolic weight. By considering the stories and qualities conveyed by each element, artists and collectors can create environments that communicate values, provoke thought, and add layers of meaning, just as Leonardo did with his careful integration of symbolic figures.

Photographic and Visual Experimentation

Leonardo’s sketchbooks reveal his experimental approach to composition, perspective, and motion. He constantly tested techniques, prepared studies, and iterated ideas before final execution. Modern creators can embrace a similar mindset, using guides such as DIY backdrop stand tutorials to explore new setups, angles, and creative possibilities. Leonardo’s legacy reminds us that mastery often emerges from curiosity and iterative experimentation, where failure and discovery are essential companions on the path to innovative expression.

Commemorative and Personal Expression

Beyond technical mastery, Leonardo’s works convey deeply personal and philosophical reflections. He often imbued portraits and religious scenes with intimate narratives, revealing the human condition in subtle ways. Contemporary collectors can capture this sense of personal expression through curated collections like love on display valentine’s canvas, which transform memories and sentiment into visual art. These modern interpretations honor Leonardo’s approach by embedding narrative and emotion into the visual experience, fostering engagement and contemplation in those who encounter the work.

Nobility and Monumental Presence

Many of Leonardo’s figures radiate nobility, authority, and compositional weight, inviting viewers to reflect on virtue, dignity, and character. These qualities can inform modern design choices, where scale, placement, and subject matter evoke presence and gravitas. Works like noble effigy artworks channel a similar sense of importance, using form, proportion, and placement to create spaces that feel curated and intentional. Leonardo’s mastery demonstrates that conveying strength through visual art requires both precision and an understanding of the viewer’s perception, lessons that continue to resonate in contemporary creativity.

Psychedelic and Surreal Inspiration

While firmly rooted in observation, Leonardo’s later works hint at imaginative exploration, blending reality with visionary ideas. This anticipates the surreal and abstract movements that would emerge centuries later. Modern collectors and creatives can embrace this spirit with pieces like psychedelic reverie art, which encourage contemplation, curiosity, and emotional engagement. By juxtaposing realistic form with imaginative concept, Leonardo taught that creativity flourishes at the intersection of observation and invention, a lesson that continues to inspire modern artistry and design.

Leonardo’s Timeless Appeal in Interiors

Leonardo da Vinci’s art continues to influence how we perceive space, balance, and visual harmony in modern interiors. His compositions exemplify the fusion of technical skill and aesthetic sensibility, inspiring decor that encourages reflection and engagement. Bringing this inspiration into contemporary homes can be achieved through collections such as living room decor ideas, which provide focal points that echo Leonardo’s sense of proportion, light, and narrative. The careful curation of pieces allows for spaces to communicate sophistication and evoke the same quiet contemplation one experiences in a gallery.

The Subtle Art of Background Control

Leonardo’s mastery of detail includes subtle manipulation of focus and depth, guiding the viewer’s eye to the most significant elements of a composition. His ability to direct attention remains a lesson in visual storytelling. Modern digital artists and photographers can emulate this through techniques like mastering background blur in Adobe Lightroom, which allows the subject to emerge from its environment with clarity while maintaining atmospheric depth. By controlling visual hierarchy, one can evoke narrative emphasis and emotional resonance, continuing Leonardo’s tradition of layered and intentional composition in contemporary mediums.

Preservation and Artistic Care

Leonardo’s works have endured centuries due to careful preservation, reminding us that art requires both reverence and technical understanding to maintain its integrity. Modern collectors and creators must similarly respect the longevity of their pieces. Tools such as Spectrafix fixative for indoor art help protect delicate mediums, ensuring that each stroke and texture remains vibrant over time. Leonardo’s dedication to precision and permanence encourages a mindfulness that transcends creation, emphasizing the importance of care, technique, and foresight in the stewardship of artistic works.

Revolutionary Portraiture and Expression

Leonardo’s portraits, from the subtle enigma of the Mona Lisa to the commanding presence of Saint John the Baptist, illustrate his ability to convey personality and narrative through expression. His understanding of human emotion remains a guiding principle for contemporary artists. Integrating pieces such as punk prestige canvas into modern interiors can emulate this dynamic, blending boldness and character into living spaces. Each artwork, like Leonardo’s subjects, becomes a point of engagement, inviting viewers to explore emotion, gesture, and the interplay between figure and context, bridging historical mastery with modern interpretation.

Harmony and Symmetry in Composition

The balance in Leonardo’s works demonstrates an acute awareness of proportion, symmetry, and visual rhythm. This concept is not limited to painting but extends to any design or spatial arrangement. Modern collectors can replicate such harmony with pieces like pure harmony wall decor, which emphasize equilibrium, tone, and cohesion. Thoughtful placement of elements within a room can mirror Leonardo’s meticulous attention to proportion, fostering spaces that are both aesthetically pleasing and psychologically calming, reinforcing the notion that structure and artistry coexist in visual design.

Myth, Fantasy, and Narrative Depth

Leonardo occasionally explored mythological themes and imaginative constructs, infusing his work with symbolic layers that resonate beyond literal representation. Today, contemporary collections like mermaids inspired decor ideas can capture similar fantastical narratives, combining wonder with aesthetic appeal. The interplay of myth and realism encourages viewers to engage intellectually and emotionally, reflecting Leonardo’s belief that art can bridge observation, philosophy, and imagination. Modern storytelling in visual spaces can echo this tradition, creating environments that inspire curiosity and exploration.

Maximizing Impact in Small Spaces

Leonardo’s compositions demonstrate that scale is relative to narrative importance; every element, no matter how small, serves a purpose. This principle translates well into contemporary spatial design, particularly in compact environments. Utilizing concepts from small space big impact ideas, one can arrange art and furniture to achieve maximum effect, drawing attention to focal points without overwhelming the observer. Leonardo’s ability to imbue even modest compositions with complexity inspires modern creators to consider scale, proportion, and strategic placement in every context.

Color and Mood in Modern Interiors

Leonardo’s subtle use of color, tone, and light demonstrates how palette influences mood and perception. His approach illustrates that emotional resonance often emerges through understated choices rather than overt dramatics. Modern interiors can replicate this effect using curated pieces such as stunning pink bedroom decor ideas, which combine color, texture, and light to evoke atmosphere. Thoughtful selection and positioning of color in living spaces can create harmony, emotional engagement, and immersive experience, reflecting Leonardo’s understanding of chromatic subtlety.

Sophistication in Form and Texture

Leonardo’s drawings and paintings reveal a sensitivity to both form and texture, capturing nuanced transitions between surfaces and volumes. This attentiveness to tactile qualities continues to inspire modern creators, as viewers respond not only to content but also to the physicality of materials. Incorporating works like pure sophistication art into interiors can create visual and sensory layers, echoing Leonardo’s balance of surface treatment, shadow, and composition. By valuing both the visual and tactile experience, contemporary spaces can achieve richness reminiscent of Renaissance masterpieces.

Leonardo’s Lasting Lessons

Leonardo’s oeuvre provides timeless insights into observation, narrative, and artistic innovation. His dedication to precision, curiosity, and experimentation transcends his era, influencing artists, designers, and collectors alike. By thoughtfully integrating modern pieces inspired by these principles, one can cultivate spaces that reflect creativity, depth, and engagement. The lessons embedded in every stroke, shadow, and composition remind us that art is both a study of the world and a mirror of human experience, offering inspiration that endures across generations.

The Human Form and Leonardo’s Legacy

Leonardo’s fascination with the human form was foundational to his art, blending anatomy, emotion, and proportion in ways that continue to inspire. His studies of muscles, gestures, and posture reveal a dedication to understanding both physical and psychological dimensions of humanity. Contemporary collectors can explore similar themes through nude inspired decor ideas, which celebrates form, elegance, and expression. By placing such works in living or creative spaces, one can foster an appreciation for anatomy and movement, echoing Leonardo’s commitment to portraying humans with accuracy, grace, and emotional depth.

Precision, Craft, and Color in Art

Leonardo’s meticulous approach extended beyond anatomy to every stroke of his brush and sketch. His works balance precision with expressive beauty, showing that craft and creativity are inseparable. Modern audiences can find inspiration in techniques that embrace both skill and exploration, such as the art of Lascaux techniques, where color, layering, and careful execution reveal the power of disciplined creativity. Leonardo’s legacy teaches that attention to detail, patience, and dedication allow visual narratives to resonate across time, bridging historical mastery and contemporary practice.

Transforming Vertical Spaces with Art

Leonardo’s compositions often considered vertical space and height, whether in altarpieces, murals, or architectural sketches. The relationship between the viewer and the artwork was crucial to his storytelling. Today, transforming tall or vertical spaces can have a similar effect, using visual flow to create narrative and engagement. For example, top staircase decor ideas allow a stairway to become a dynamic gallery, capturing attention while guiding movement. This principle mirrors Leonardo’s mastery of perspective and proportion, encouraging designers to think about the vertical axis as a canvas for storytelling.

Imagination and Dreamlike Expression

While grounded in observation, Leonardo often allowed imagination to flourish in his sketches and conceptual works. This balance between realism and vision inspires modern explorations of surreal and abstract ideas. Pieces like quantum dreamscape canvas embody this synthesis, inviting viewers into dreamlike realms where observation meets invention. Leonardo’s work demonstrates that creativity thrives when empirical study meets imaginative interpretation, a lesson that continues to inspire artists to bridge the tangible and the visionary in their practice.

Parallel Worlds and Visual Exploration

Leonardo’s art often hinted at alternative perspectives and hidden narratives, subtly expanding the viewer’s understanding of space and story. Modern interpretations continue this exploration with works that challenge perception and invite curiosity. Collections such as quantum realms canvas use abstract forms and dynamic colors to evoke layered realities, reflecting Leonardo’s interest in complexity and depth. By engaging with such pieces, viewers are encouraged to look beyond surface appearances, discovering multiple layers of meaning and inviting personal interpretation.

Inspiration in Professional Environments

Leonardo’s principles of observation, proportion, and aesthetic balance are not confined to galleries—they can inform productive and creative spaces as well. Integrating art thoughtfully into offices can stimulate focus, creativity, and dialogue. For example, office inspired decor ideas allows professionals to bring visual inspiration into workspaces, fostering an environment where balance, elegance, and contemplation coexist. Leonardo’s dedication to mastery reminds us that thoughtful surroundings enhance intellectual engagement and emotional connection.

Mastering Light and Detail

The subtlety of Leonardo’s use of light demonstrates the importance of observation in rendering depth and texture. His works illustrate how careful attention to luminosity creates dimensionality and narrative. Modern photographers and artists can explore these principles through techniques such as mastering HDR photography, capturing detail and vibrancy in ways that echo Renaissance precision. Understanding the interaction of light, shadow, and surface continues to be essential for conveying mood, volume, and realism in visual compositions.

Style Optimization in Compact Spaces

Leonardo’s work proves that impact is not only determined by scale; careful composition ensures that even smaller works can carry immense meaning. This lesson applies to modern interiors, particularly in compact spaces where visual economy is key. Techniques and advice from maximizing style in small spaces demonstrate how curated art can enhance perception, depth, and sophistication without overwhelming the environment. Leonardo’s legacy reminds us that mastery lies in thoughtful arrangement, whether in painting or design.

Flora, Fauna, and Environmental Nuance

Leonardo’s fascination with plants, flowers, and nature is reflected in the delicate detailing of his sketches and paintings. Capturing this natural beauty fosters both aesthetic pleasure and observational skill. Contemporary collectors can explore this theme through works like sable alabaster flora, which celebrate organic forms and intricate detail. Leonardo’s attention to natural patterns and the subtleties of texture teaches that observing the world with patience and care enriches both creativity and comprehension of life’s intricacies.

Color, Emotion, and Sensory Impact

Color was a critical vehicle for emotion in Leonardo’s paintings, whether conveying serenity, tension, or vitality. Modern creators can use color to enhance emotional response, narrative, and ambiance within a space. For instance, ruby infusion canvas employs vivid tones and layered composition to evoke feeling, energy, and curiosity. Leonardo’s integration of color, form, and light continues to guide artists in producing work that engages viewers intellectually, emotionally, and sensorially, underscoring the timeless resonance of his mastery.

Conclusion

Exploring the top 10 paintings of Leonardo da Vinci offers a profound insight into the mind of one of history’s most extraordinary artists and polymaths. Da Vinci’s work transcends the boundaries of art, science, and human understanding, combining meticulous observation, technical mastery, and deep emotional resonance. Each painting not only reflects his unparalleled skill in composition, perspective, and anatomy but also reveals a remarkable ability to capture the human spirit, emotions, and the subtle interplay of light and shadow. From the serene yet enigmatic smile of the Mona Lisa to the dramatic intensity of The Last Supper, these masterpieces continue to captivate audiences centuries after they were created.

One of the most striking features of Leonardo’s paintings is his pioneering use of techniques such as sfumato and chiaroscuro. These methods allowed him to create lifelike transitions, depth, and realism that were revolutionary for his time. Through these techniques, Leonardo imbued his subjects with a sense of vitality and presence that draws viewers into a silent dialogue with the artwork. Beyond technical prowess, his works often incorporate complex symbolism, philosophical ideas, and scientific observations, demonstrating that art and knowledge were inseparable in his vision. This synthesis of creativity and intellect is a hallmark of his enduring legacy.

Leonardo’s paintings also reveal his fascination with humanity. Many of his works focus on the subtleties of facial expression, gesture, and emotion, capturing moments of introspection, contemplation, and connection. Lady with an Ermine and Ginevra de’ Benci are exemplary in portraying inner life and character with astonishing realism. Even religious works, such as The Last Supper or The Annunciation, blend spiritual narrative with intimate human experience, bridging divine storytelling with relatable human emotion. This ability to communicate both universality and individuality ensures that his paintings remain relevant and moving across generations.

Furthermore, studying these masterpieces highlights Leonardo’s role as a visionary thinker and innovator. He approached each painting with curiosity and experimentation, meticulously studying anatomy, light, and the natural world to inform his art. His notebooks, sketches, and preparatory studies reveal the depth of observation and planning behind every stroke, reminding us that mastery is built through patience, practice, and intellectual rigor. This dedication is a testament to the fusion of artistry and science that defined the Renaissance and continues to inspire artists, scientists, and thinkers today.

In conclusion, Leonardo da Vinci’s top 10 paintings are more than historical artifacts; they are living embodiments of creativity, curiosity, and human expression. They demonstrate how art can transcend time, language, and culture to evoke emotion, provoke thought, and inspire wonder. By exploring these works, we not only appreciate Leonardo’s technical brilliance but also gain insight into the mind of a man whose vision combined art, science, and humanity in ways that remain unmatched. Celebrating these masterpieces reminds us of the timeless power of creativity and the enduring legacy of one of history’s greatest geniuses—whose work continues to shape our understanding of art, life, and the infinite possibilities of human imagination.