Photographing fire is a captivating pursuit that blends technical skill with artistic expression. The flame’s unpredictable nature and vibrant motion offer endless possibilities for visual storytelling. Whether you’re capturing the subtle flicker of a candle or the bold dance of fire in performance art, working with fire demands a strong understanding of both photographic technique and safety. This in-depth guide will walk you through fire photography from a practical and creative perspective, helping you produce stunning images without compromising on safety or vision.

Safety Comes First in Fire Photography

Before you even think about pressing the shutter, safety must be your first consideration. Fire is as dangerous as it is beautiful. Without caution, a simple creative shoot could lead to severe accidents. Always plan your session with safety gear and awareness.

Choose a location that is open, spacious, and free from combustible materials such as dry foliage or paper-based props. Urban rooftops with proper ventilation or designated fire-safe zones are better than forests or grassy fields. Avoid shooting in windy conditions, as gusts can cause fire to shift suddenly and unpredictably.

Always maintain a safe buffer zone between your fire source and yourself, your subject, or any props. This is particularly important when photographing people. Keep their clothing fitted, and ask them to tie back long hair. Use flame-resistant materials when possible.

If you’re a beginner, start with minimal fire elements like tea lights, candles, or handheld sparklers. These can be controlled more easily and pose far less risk than open flames or accelerant-based torches.

Bring a fire extinguisher or a bucket of water to every shoot involving fire, regardless of scale. A dry chemical extinguisher is suitable for most small flames. Familiarize yourself with how it operates before arriving at the location. Never rely solely on the flame’s appearance to gauge safety. A fire that appears manageable can become dangerous in seconds if conditions change.

After your session, confirm that all flames and embers are fully extinguished. Double-check your environment for smoldering materials that could reignite hours later. Fire safety is not just about prevention—it’s about responsible cleanup.

Photographing Fire: Understanding the Technical Framework

Photographing fire presents one of the most visually thrilling challenges in photography. Fire behaves differently from any other light source, combining both luminance and movement in unpredictable ways. It’s alive—constantly changing, pulsing, shifting, and flickering—producing varying tones of color, contrast, and shadow. To capture it with precision, photographers must understand how fire behaves optically and how to adapt camera settings to preserve both its drama and its intricacy.

Whether your subject is a single flame or a roaring blaze, mastering exposure is the foundation of successful fire photography. The delicate interplay between highlights and shadows, motion and stillness, becomes a delicate balancing act that rewards technical control and creativity.

How Fire Behaves in the Frame

Unlike static subjects, fire emits intense and uneven light, often with rapidly changing brightness levels. At any moment, flames may leap higher, dim, or split into multiple streams. This creates sharp contrasts within your frame, making it easy to overexpose certain areas while others remain deeply underexposed.

Fire also reflects off surfaces—particularly metallic or glossy ones—so controlling where and how it spreads within the composition is critical. If the flame is your only light source, it becomes both your subject and your illuminator. This duality introduces complexities into metering and white balance that you’ll need to compensate for through precise settings.

Additionally, firelight is inherently warm. It radiates color temperatures ranging from approximately 1700K for candlelight to over 3000K for large bonfires. The resulting tones are orange, red, and yellow, often casting those hues onto surrounding surfaces and subjects. These tones are beautiful but may overpower color fidelity in portraits or indoor scenes unless intentionally balanced.

Optimal Aperture Settings for Fire Photography

Aperture, the opening in your lens that controls how much light reaches your camera sensor, plays a major role in shaping the clarity and impact of flame photos. When shooting fire, photographers are often tempted to open the aperture wide to let in more light. However, this can produce an overly shallow depth of field, making much of the flame’s texture and environment fall out of focus.

To capture detailed, sharp flame structures—especially in log fires, fireplaces, or structured compositions—smaller apertures such as f/8, f/9, or even f/11 are ideal. These settings extend your focus range, ensuring that more of the flame’s contours and nearby elements remain in sharp relief.

The trade-off is that smaller apertures admit less light. In low-light fire scenes, this can result in underexposed images unless you compensate through ISO or shutter adjustments. It's a delicate equation that needs to be solved in real time, and being familiar with exposure triangles helps.

Adjusting ISO for Clean, Bright Images

ISO refers to your camera sensor’s sensitivity to light. Raising ISO values helps you achieve a brighter exposure when ambient light is limited, such as when fire is your only light source. However, increasing ISO also risks introducing noise, which can reduce image quality—especially in darker areas.

Modern DSLR and mirrorless cameras have significantly improved ISO performance. On many models, ISO 800 to 1600 provides clean results, allowing you to shoot with smaller apertures or faster shutter speeds without sacrificing too much detail.

If your camera includes in-body noise reduction or if you’re shooting in RAW format, you can further refine the image in post-production. Always expose for the highlights when shooting fire, as blown highlights in flames are difficult to recover. It's better to underexpose slightly and adjust shadows later than to overexpose and lose texture in the brightest parts of the flame.

Shutter Speed and Motion Control

Fire is a moving subject, and its motion can be either frozen or artistically blurred depending on the shutter speed you use. If you're aiming for crisp, still shots that isolate the flame and its shape, use faster shutter speeds—such as 1/200s or 1/400s—especially when capturing fireworks, torches, or candles flickering in the breeze.

On the other hand, if your goal is to illustrate fire’s fluidity—such as trails from a sparkler or the rhythmic arcs of a fire performer—then slower shutter speeds are essential. Use exposures of 1 to 5 seconds or even longer. This allows your sensor to capture the movement over time, transforming the fire into artistic streaks or glowing patterns.

To achieve clean long exposures, a tripod is non-negotiable. Camera shake at slower shutter speeds will blur the entire image, not just the moving parts. For additional stability, use a remote shutter release or a delay timer to eliminate shake from pressing the button.

Be mindful that long exposures also allow more ambient light to seep into the frame. Depending on your environment, this can either enrich your photo or introduce distractions. Adjust accordingly by scouting your location in advance and controlling background light sources.

Choosing the Right Focus Method

Autofocus systems—especially in low light—often struggle with flames. The rapid flicker and lack of defined contrast in fire can cause the lens to hunt back and forth, missing focus entirely. Many cameras default to contrast-detection autofocus in dim lighting, which is not well-suited for fire scenes.

Manual focus gives you far more control. By switching your lens to manual and focusing on the precise area where fire will appear or perform, you eliminate dependence on your camera’s focus system. Zoom in digitally on your viewfinder or live view to check sharpness, then lock the focus ring.

For stationary flames such as candles or fireplace logs, this approach is simple and highly effective. For dynamic fire sources like sparklers or flame throwers, pre-focusing on a point where action will occur can help ensure consistency across a series of frames.

In portrait settings illuminated by firelight, use manual focus to hone in on your subject’s eyes or face—particularly when working with low apertures like f/1.8 or f/2. These settings create a narrow focus plane, and autofocus often chooses unintended areas like the flame itself rather than the subject’s features.

Metering and Exposure Compensation

Cameras are designed to meter for average brightness, and a bright flame in a dark environment can fool the metering system into underexposing the rest of the image. Use spot metering to evaluate exposure based on the flame or a subject near the flame, and consider dialing in positive exposure compensation (+0.3 to +1.0) if your subject appears too dark.

In Manual mode, you have full control over all three exposure settings—shutter, aperture, and ISO. This mode is often the best for fire photography, as it allows you to balance settings precisely based on your scene and creative goals.

Evaluative or matrix metering systems may also work well in evenly lit scenes with multiple flames, such as candlelit tables or torch-lit trails, but they still require occasional override to get the exposure right.

Shooting Format and White Balance

Shooting in RAW format is crucial for fire photography. RAW files preserve more data than JPEGs, allowing you to adjust white balance, recover highlights, and fine-tune shadows in post-production without degrading image quality.

As for white balance, leaving your camera on auto may result in cooler-toned images, as the system attempts to neutralize the warm hue of the fire. Instead, use a manual Kelvin setting between 2000K and 3000K to retain the rich warmth of flames.

Alternatively, selecting a “Tungsten” or “Incandescent” white balance preset can often render a pleasing warmth that matches the scene’s mood, though you should adjust based on the color temperature of your flame source.

Capturing Movement in Fire Using Long Exposures

One of the most expressive and visually dynamic techniques in fire photography involves capturing motion through long exposures. While fire is already mesmerizing to the eye, its kinetic qualities can be amplified when photographed with slow shutter speeds. Rather than freezing the flame mid-action, long-exposure photography allows you to illustrate its motion over time—transforming it into glowing trails, fluid shapes, and even abstract forms.

This technique can convert simple sparklers into glowing calligraphy, bonfires into radiant vortexes, or fire dancers into streaks of energy frozen in time. Done right, long exposures not only document a flame's path but elevate its character into something cinematic and surreal.

The Visual Power of Fire in Motion

Fire is never still. It flickers, twists, stretches, and sometimes spirals through air currents. When your camera shutter remains open longer than the typical snapshot, it records all of these movements in one composite image. This results in light trails that visually represent the flame’s journey—a kind of visual echo of its dance.

While fast shutter speeds capture sharp stills, they miss out on this expressive potential. A long exposure, by contrast, turns a torch swing into a glowing arc, or a tossed ember into a string of light. The unpredictability of fire adds to the uniqueness of every frame, ensuring no two shots will be identical.

This technique is not only ideal for creative expression but also useful for low-light situations where light from the flame alone can properly expose a scene. When used with purpose, slow shutter speeds transform fire photography from a documentary effort into a creative narrative medium.

Preparing for a Long-Exposure Fire Shoot

Before you begin capturing fire in motion, it's crucial to plan your shoot with both creativity and safety in mind. Unlike static photography, long-exposure fire shoots require more control over the environment, gear, and subjects involved.

First, choose a secure, open area that allows for movement and has no immediate flammable hazards. This is especially important if you're photographing moving fire sources like spinning torches or fire poi. Ensure there's no dry vegetation, loose fabrics, or plastic materials that could catch fire from a rogue flame.

Bring essential safety gear like a fire extinguisher, fire blanket, or at minimum, a large bucket of water. Have an assistant on standby if the shoot involves performers or elaborate fire tools.

Next, stabilize your camera with a sturdy tripod. Even the slightest hand movement will ruin a long-exposure frame. If possible, use a remote shutter release or set your camera to a short timer delay to eliminate shake from pressing the shutter manually.

A lens hood can also help shield your lens from stray sparks or ambient light spill, and a lens cleaning cloth is useful for wiping off soot or smoke residue after the session.

Understanding Shutter Priority Mode and Manual Control

Long-exposure photography starts with shutter speed. Most DSLR and mirrorless cameras offer Shutter Priority mode (often labeled "S" or "Tv") that lets you set the shutter duration while the camera automatically adjusts aperture and ISO to achieve proper exposure.

For light trails created by sparklers, fire fans, or torches, begin with shutter speeds between one and five seconds. This allows enough time to record smooth, continuous motion. For more elaborate performances or larger flames, try exposures of 8, 10, or even 20 seconds.

In darker environments or where you want more granular control over light and depth of field, switch to full Manual mode. Here, you can dictate shutter speed, aperture, and ISO independently, which gives you total creative freedom.

If the fire performer or flame is the only source of light, a wider aperture (like f/2.8) may help capture more ambient glow without needing to boost ISO too high. If you're including background scenery or additional lighting, try smaller apertures like f/5.6 to f/8 for extended depth of field.

ISO should remain as low as possible to reduce noise—start at ISO 100 or 200. In extremely dark settings, raising it slightly to ISO 400 or 800 is fine, especially if your camera handles low-light noise well.

Composition and Framing During Fire Motion

When capturing fire motion, it’s not just about exposure—it’s also about how you compose the frame to best tell the story of that movement. Think in terms of arcs, spirals, loops, or linear sweeps. Predict how the flame will move, and pre-frame the shot to include space for that motion to evolve.

Leave negative space in the direction the flame will travel. For instance, if your subject is swinging a torch clockwise, place them on the left third of the frame, leaving space for the trail to unfold on the right. If someone is running with a fire source, lead your composition ahead of them, just like panning with motion in sports photography.

Consider the environment, too. Shooting in a natural setting like a forest clearing or rocky beach can add context and richness to your image. However, if your aim is abstraction, a dark, clean background will let the fire trails stand out in isolation.

Smoke can either enhance or obscure your shot. In backlit scenes, it catches light beautifully, but it can also soften contrast and make flames less defined. Adjust your angle to control how much smoke enters the frame.

Working with Fire Performers and Live Movement

If your fire shoot involves a live performer—such as a fire dancer, poi spinner, or staff handler—coordination becomes crucial. Fire performers need to be experienced, fully geared, and briefed on your intentions.

Let them know how long your exposures will be so they can match their movement speed accordingly. A slow swing of a flaming poi during a 5-second exposure creates an elegant arc, while a fast spin in the same time frame may result in a blurred, unrecognizable streak.

Discuss choreography in advance. If you’re aiming for specific patterns like hearts, circles, or figure-eights, rehearse these movements in dry runs before lighting the tools. Use chalk, glow sticks, or other safe materials to practice paths before introducing fire.

Keep a safe distance when framing your shots, and zoom in with a telephoto lens if needed. Your safety and that of the performer must always take precedence over the image.

Controlling Ambient Light and Color Temperature

Long exposures are sensitive not only to flame movement but also to ambient light. Streetlights, moonlight, passing cars, or nearby buildings can all influence your image, often introducing unintended color shifts or overexposure.

Scout your location ahead of time to identify potential light sources. If you can’t eliminate ambient lights, use them creatively as part of your scene—perhaps as background bokeh or environmental glow.

Color temperature also matters. Flames emit warm tones—typically in the 2000K to 3000K range. Adjust your white balance accordingly to retain the warmth of the fire or to neutralize it, depending on your artistic goal. Custom Kelvin settings often work better than Auto White Balance, which may misinterpret the scene and cool down the image unnecessarily.

If photographing flames with different fuel sources—like colored flares or chemical fire tools—be aware of how those colors will interact. Editing later in RAW helps recover accurate tones without banding or oversaturation.

Post-Processing and Enhancing Fire Trails

Post-production is where your long-exposure fire images come to life. Use software like Lightroom or Capture One to enhance contrast and clarity around the flame trails. Use local adjustments to boost the definition of the trails while maintaining the softness of the background.

If any hotspots are blown out, recover highlights where possible. Likewise, lift shadows slightly to reveal subtle movement or ambient textures in dark areas. Noise reduction tools can help clean up high-ISO areas, especially in long night exposures.

Cropping, straightening, and refining composition digitally is also encouraged, especially if the trails didn’t land exactly where expected in-camera.

Shooting Fire Against a Dark Background

Photographing flames against a dark backdrop allows their shape, movement, and chromatic intensity to become the focal point of the image. This approach strips away distractions and visual noise, letting the luminous qualities of fire emerge in pure, dramatic isolation. Whether it's a solitary candle flame or a fire dancer’s swirling torch, isolating fire against black space brings out the ethereal qualities that define this element in motion and stillness.

Dark-background fire photography is especially useful for conceptual work, abstract compositions, product shots with mood lighting, and atmospheric portraiture. By removing competing visual elements, the flame becomes both light source and subject—imbuing every frame with intensity, contrast, and mystery.

Why Fire Stands Out Best Against Darkness

From a visual standpoint, fire thrives on contrast. The brighter and more defined the flame, the more it benefits from a surrounding environment that emphasizes its glow. A dark background serves this function perfectly, making the edges of the flame crisp, the colors more saturated, and the scene more immersive. The glowing edges of a flame—ranging from blue at the base to orange or yellow at the tips—are often lost in cluttered compositions or light-polluted settings. Against a black or dark background, those transitions become vividly visible.

The human eye is naturally drawn to areas of light within darkness, and photography mirrors this instinct. A flame suspended in shadow activates attention, curiosity, and emotion. It’s also more forgiving when balancing exposure since you won’t need to account for ambient light levels or color casts from your surroundings.

Technique One: Using a Matte Black Physical Backdrop

One of the simplest and safest ways to achieve a black background is to place a matte black surface several feet behind the flame. This can be done indoors or outdoors, as long as the material used is fire-safe and non-reflective.

Ideal materials include:

-

Thick black cardboard or foam board with a non-gloss finish

-

Fire-retardant cloth such as black velvet or duvetyne

-

Matte-painted wooden panels or backdrop paper designed for photography

Avoid materials with sheen or reflective coatings, as these can catch stray light from the flame and ruin the clean separation. Position the flame a minimum of one meter (about three feet) in front of the backdrop. This distance minimizes the risk of combustion and helps the background remain out of the depth-of-field focus range, enhancing the blur and overall darkness.

Set your flame source—candle, lighter, or torch—on a stable, non-flammable base. Avoid using plastic, thin metal, or paper-based containers. Choose ceramic, stone, or sand-filled holders for maximum safety.

Use a prime lens with a wide maximum aperture, such as a 50mm f/1.4 or 85mm f/1.8, and shoot wide open to achieve shallow depth of field. This reduces the likelihood that any background texture or imperfection will become visible in the shot. The wide aperture also allows more light from the flame to reach your sensor, helping achieve proper exposure without relying on high ISO levels.

Lock in focus on the sharpest part of the flame—typically near the base—and keep your ISO as low as possible to preserve clean blacks. Use manual focus, as autofocus often struggles in dimly lit settings and may lock onto the wrong part of the scene.

Technique Two: Shooting in a Completely Dark Environment

An alternative to a physical backdrop is shooting in total darkness. This method removes any visible background entirely by relying solely on the flame to light the scene. It’s one of the cleanest ways to isolate fire and works particularly well for small-scale setups like candles, matchsticks, or incense burners.

To achieve this, find or create a space devoid of ambient light. A windowless room at night, a photography blackout tent, or a makeshift box enclosure lined with black fabric can all serve as ideal shooting environments. Eliminate any nearby artificial light sources including lamps, screen glow, or residual outdoor lighting.

Your camera settings will need careful adjustment. Begin with a wide aperture—around f/1.4 to f/2.0—and a shutter speed that complements the flame’s motion. For static subjects like a candle, shutter speeds between 1/60 and 1/200 work well. If capturing subtle flickers or smoke trails, slower speeds of 1/30 can add artistic blur.

Use a tripod or stable surface to prevent camera movement. Even minor shakes become exaggerated in dim settings. A remote trigger or camera app can eliminate contact-induced blur entirely.

Since there are no external light sources, the flame will be the only thing lighting your scene. Exposure becomes easier to balance but requires attention to the brightness of the flame. If the image is too bright, close the aperture slightly or increase your shutter speed. Avoid using ISO settings above 800 if possible to retain rich blacks in the background.

Refining and Enhancing the Black Background in Post-Processing

Even with careful setup, small imperfections, light spill, or smoke patterns may appear in the background. Post-processing is a vital step in ensuring your background remains clean and supports the visual drama of the flame.

Start by adjusting black levels and contrast in your editing software. Tools like the tone curve, shadows slider, and black point adjustment help remove any ambient residue and flatten distracting gradients. Avoid overprocessing, as extreme black clipping can produce unnatural edges around the flame.

Use selective adjustment tools to darken only the background. In Lightroom or Capture One, the masking tools can isolate the flame, allowing you to apply graduated darkening to the surrounding area without affecting the main subject. This preserves the natural glow and gradient of the flame while enhancing its prominence.

Spot removal tools can eliminate dust, burn marks, or reflections that disrupt the minimalist aesthetic. You can also desaturate or color grade the background subtly for artistic interpretation, though this is typically unnecessary for a pure black backdrop.

Shooting in RAW format ensures you have maximum flexibility to adjust tonal range without degrading the image. RAW files preserve flame details that might otherwise be lost in JPEG compression, particularly in the highlight and midtone regions.

Incorporating Composition Techniques into Minimalist Fire Shots

Despite the simplicity of a black background, composition remains important. Experiment with placement of the flame within the frame using the rule of thirds, central framing, or negative space strategies. A lone candle positioned off-center can evoke solitude, while a centered torch can emphasize symmetry and balance.

Include subtle elements like curling smoke trails, reflections on glass, or shadow play on the flame holder. These additions create visual layers while keeping the scene clean. Just ensure they don’t detract from the flame itself.

Use vertical orientation for tall flames and horizontal framing when the subject includes multiple elements, like grouped candles or flames in a row. Try changing angles slightly—shooting from below can make the flame feel more powerful, while an overhead view introduces a sense of detachment or observation.

Creative Applications of the Technique

Photographing fire against black backgrounds has numerous applications beyond simple artistic experiments. It's popular in commercial product photography for items such as candles, incense, torches, or lighters. The darkness lends luxury and drama, drawing attention to glow and texture.

Conceptual portraiture also benefits from this style. When combined with partial lighting or selective focus, fire becomes a storytelling device—illuminating only parts of a face or casting dramatic shadows for cinematic effect.

Fine art photographers may use this technique to explore themes like solitude, illumination, transformation, or impermanence. The minimalist nature of the image makes it suitable for gallery exhibitions, digital art compositions, and even printed photo books with narrative arcs.

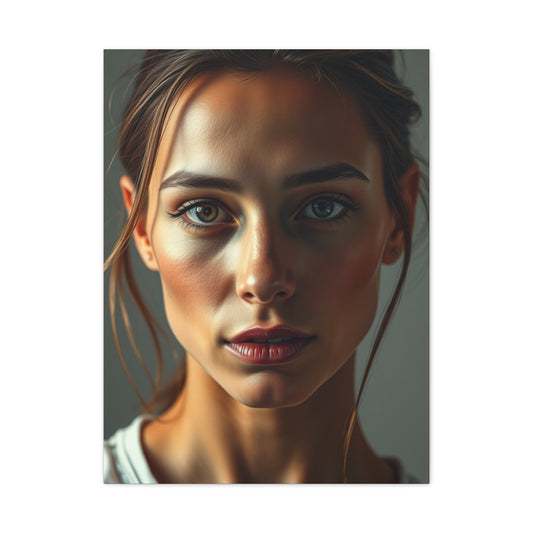

Portrait Lighting Using Fire

Fire, when used thoughtfully, becomes one of the most evocative tools in portrait photography. Its natural glow carries warmth, unpredictability, and a sense of ancient connection to the human spirit. From a single candle illuminating a face to sparklers dancing in the eyes of a subject, fire brings intimacy and mystery to portrait work that artificial lights often fail to replicate. It introduces an organic radiance that flatters skin tones, enhances mood, and adds atmospheric depth to compositions.

Unlike softboxes or LED panels, fire produces asymmetrical, flickering light that feels alive. It interacts with surfaces dynamically, throwing gentle shadows and warm tones that shift subtly from moment to moment. This makes portraits illuminated by flame feel more personal, poetic, and raw. The emotional weight fire introduces can be adapted to a wide range of visual narratives—romantic, melancholic, mysterious, or celebratory.

Understanding Fire as a Light Source in Portraiture

When using fire to light portraits, one must first understand its properties as a light source. Unlike controlled studio lighting, fire emits light that is inconsistent in both color temperature and brightness. A small flame, such as a candle or match, produces a localized and weak glow—often between 1700K and 2200K in color temperature. This warmth is pleasing to the human eye and suits portraiture well but can be tricky for exposure.

Larger flames, such as from a bonfire or torch, emit more illumination but introduce harsher gradients and quicker movement in the light source. These are better suited to outdoor portraiture or dramatic themes, where the unpredictability of the flame is welcomed as part of the artistic process.

To effectively light a subject’s face using fire, you must account for its softness, its rapid decay in brightness over distance, and the way it interacts with reflective surfaces, skin texture, and surrounding elements.

Positioning the Flame for Balanced Illumination

The positioning of the flame relative to your subject’s face is one of the most important decisions in your setup. Placing the flame slightly to the side and at or slightly above eye level tends to yield the most flattering results. This setup mimics classic portrait lighting techniques like Rembrandt or loop lighting, creating gentle contrast on the face while retaining detail in both eyes.

Avoid placing the flame directly below the subject’s chin, as this creates harsh upward shadows that distort facial features and produce a theatrical or sinister effect. This style may be useful for horror-themed portraits or dramatic storytelling but should be avoided for neutral or flattering aesthetics.

Side-lighting with fire produces sculptural depth. It defines cheekbones, eye sockets, and jawlines with natural fall-off. Position the flame at a 45-degree angle from the subject to create a dynamic light-shadow transition across their face.

If using multiple flame sources—such as several candles or lanterns—distribute them strategically to wrap the subject in light while avoiding hotspots that could blow out parts of the image or create unwanted lens flare.

Choosing the Right Camera Settings for Fire-Lit Portraits

Fire’s limited output demands careful selection of camera settings. Use lenses with wide apertures, such as f/1.4, f/1.8, or f/2.2. These allow more light to reach your sensor and create a shallow depth of field that isolates the subject beautifully against soft bokeh or darkness.

Wide apertures are essential for maintaining image brightness in low-light scenes where fire is the only illumination. They also produce that cinematic blur, where flames in the background melt into glowing orbs and foreground features remain sharp and expressive.

Shutter speed should remain fast enough to avoid blur from subject movement or flame flicker. If your subject is still and the flame steady, shutter speeds between 1/60 and 1/125 of a second work well. For more active scenes or outdoor firelight, consider faster speeds and compensate with a higher ISO.

ISO settings will vary depending on the brightness of the flame and the ambient conditions. Begin with ISO 800 and increase incrementally if needed. Many modern mirrorless and DSLR cameras handle ISO up to 3200 gracefully, preserving detail while introducing minimal grain. When shooting in RAW, minor noise can be removed during post-processing without affecting the overall image integrity.

Focus should be set manually when possible, as autofocus may struggle in low light or lock onto the flame instead of the subject’s eyes. Use live view or magnification features to ensure precise focus, especially when shooting at shallow depths of field.

Enhancing Firelight with Reflective Surfaces

Because fire offers a narrow, directional light spread, it may not fully illuminate the subject’s entire face or surrounding features. To maintain a natural yet fuller exposure, introduce reflectors into your setup.

Simple tools like white foam boards, gold reflectors, or metallic surfaces placed on the opposite side of the flame will bounce warm light back onto the subject’s face. This helps reduce shadow intensity without neutralizing the unique atmosphere that fire creates.

For example, placing a silver reflector opposite a candle can soften the shadows on the darker side of the face while retaining the moody, intimate ambiance. A gold reflector enhances warmth, further enriching skin tones and complementing the flame’s color temperature.

Avoid using flash or LED lights unless they are diffused and matched in temperature, as they often clash with the soft, warm glow of fire and break the illusion of natural flame-based illumination.

Working with Different Fire Sources for Portraits

Each type of flame source presents unique advantages and challenges:

-

Candles are ideal for close-ups and intimate mood portraits. They are safe, easy to control, and emit a soft, steady light. Use multiple candles for broader illumination or to introduce layered lighting.

-

Sparklers are dynamic and create a celebratory or whimsical effect. Use a fast shutter speed to freeze their motion or a slow shutter for glowing trails behind your subject.

-

Lanterns provide more controlled and even illumination, perfect for storytelling portraits or scenes with historical or rustic ambiance. Their shape and structure can also serve as visual anchors in composition.

-

Bonfires create high-output light with broad diffusion. Ideal for group portraits or environmental portraits in outdoor settings. However, their light can be harsh—position subjects at a distance and balance exposure accordingly.

Be mindful of the proximity between flame and subject. Fire should be close enough to cast light but not so close as to pose safety risks or create uneven highlights on skin. Monitor your subject’s comfort and adjust the setup if they feel excessive heat.

Background and Environmental Considerations

When composing fire-lit portraits, consider your background and setting. A clean, dark background helps the flame stand out and maintains focus on your subject. In contrast, shooting outdoors at twilight or night can include subtle background details that complement the scene, such as distant trees, stars, or architectural features.

If your subject is holding the flame source, such as a candle or lantern, have them look slightly toward the light. This not only improves the lighting angle but also creates a contemplative or introspective expression.

Smoke trails from fire sources can add mood and depth if used thoughtfully. Let smoke drift naturally and use side or back lighting to catch its texture. However, too much smoke can obscure the subject, so keep it balanced.

Post-Processing Fire-Lit Portraits

Post-processing can elevate the emotional tone of fire-lit portraits. Adjust white balance to maintain or enhance the warmth of the flame. Avoid cooling the image too much, as it defeats the purpose of using fire as a natural light source.

Increase contrast slightly to give the flame more definition, and use local adjustments to lift shadow detail in the subject’s face without flattening the image. Clarity and texture adjustments can help define facial features in low-light conditions, while noise reduction ensures smooth skin tones at higher ISO values.

Mask out the flame area before applying any heavy editing, as over-processing can easily distort its natural shape and color gradients.

Artistic Concepts and Shooting Ideas with Fire

Once you’ve mastered the basics, expand your creative fire photography portfolio by experimenting with thematic ideas and storytelling.

Capture a bonfire gathering to showcase candid expressions and warm ambient light. The fire serves as both a light source and a mood setter. Expose for the subjects’ faces and recover any clipped highlights in post-production.

Create silhouettes by placing your subject between the fire and your camera. This technique works well with large flames like bonfires or torches. Shoot in low-light conditions to emphasize the subject’s shape without revealing facial detail.

Use a telephoto lens, such as a 70–200mm, to photograph fire details from a safe distance. This approach is ideal for isolating textures—like charring wood, flickering sparks, or delicate tongues of flame—without putting yourself or your equipment in harm’s way.

To create bokeh using fire, use a wide aperture lens and place the flame in the background. Small, bright sources like sparklers produce stunning round bokeh. This can add a magical, whimsical quality to portraits or still-life scenes.

For visual rhythm, arrange candles in patterns or groups. Photograph them from above or at eye level for different effects. Try varying the flame sizes—some lit, some just extinguished—to introduce contrast and depth.

If you get the chance to photograph a professional fire performer, you’ll challenge your skills in action photography. You’ll learn to work with erratic lighting, moving subjects, and quick composition. Set your camera to burst mode, increase your ISO as needed, and shoot at fast shutter speeds to capture flame patterns mid-motion.

Use torchlight in dramatic locations like archways, ruins, or forests to create storytelling images. These settings give a cinematic quality to your work and emphasize the interplay between fire and environment.

To simulate light leaks, hold a small flame—like a lighter—slightly in front of your lens. Position it to just graze the frame and shoot with a wide aperture to blur the flame into colorful streaks. Exercise extreme caution and avoid getting close enough to damage your lens.

Seek fire in unconventional places. Lantern festivals, traditional celebrations, incense rituals, or even kitchen stoves can provide fascinating flame-based photo opportunities. Experimenting with these sources lets you explore fire as a cultural and symbolic element, not just a visual one.

Conclusion: Bringing Vision and Vigilance Together

Fire photography is a rich, demanding genre that rewards attention to detail and creative bravery. The flicker of flame can communicate emotion, movement, warmth, and mystery—all within a single frame. But with its potential comes real risk. Successful fire photographers understand that mastery requires equal parts vision and vigilance.

By prioritizing safety, understanding the behavior of light and exposure, and exploring both technical and imaginative possibilities, you’ll transform fire into a storytelling device as dynamic as your subjects. Whether you're lighting a portrait with a candle or capturing trails from fire dancers, the flame becomes your collaborator in shaping visual narrative.