Photography is an ever-evolving art form, but one aspect that has remained timeless is the use of limited color palettes to evoke emotion and convey visual stories. Two of the most commonly referenced styles within this domain are monochrome and black and white photography. While they may seem identical on the surface, these two methods carry distinct characteristics, histories, and creative implications. Understanding their differences not only sharpens your photographic vocabulary but also enables you to make more intentional choices in both capture and post-production. Whether you're exploring the aesthetics of minimalism or aiming to strip your image down to its most powerful elements, knowing how and when to use monochrome versus black and white can transform your artistic output.

A Timeless Medium: Ilford HP5 Plus 400

For photographers delving into black and white film photography, Ilford HP5 Plus 400 remains a preferred choice due to its versatility, exceptional sharpness, and balanced grain structure. This classic film stock performs beautifully under diverse lighting conditions and is well-suited for expressive grayscale imagery. Its wide exposure latitude and tonal range make it ideal for mastering light manipulation and crafting high-impact, detail-rich photographs.

The Essence of Monochrome Photography

Monochrome photography is a visual language rooted in simplicity, yet capable of expressing profound complexity. At its foundation, it represents an image composed entirely of varying shades, tints, and tones derived from a single color. This makes it fundamentally different from full-color photography, which involves a spectrum of hues. A monochromatic image is unified by one dominant color or hue family, allowing the photographer to concentrate on structure, light play, mood, and emotion without the visual noise of multiple colors competing for attention.

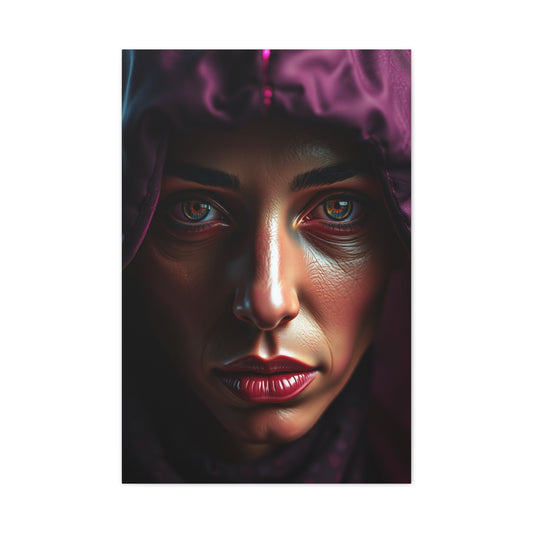

Though often conflated with black and white photography, monochrome encompasses a broader definition. It includes any image built from a solitary hue and its tonal range—whether it’s the deep, calming blues of cyanotype, the nostalgic browns of sepia, or a highly stylized red, green, or even magenta palette. This creative constraint offers more than just aesthetic appeal; it directs the viewer’s gaze to elements such as texture, form, geometry, and the interplay of shadows and highlights. Without color variety to distract the eye, the brain interprets the photograph more abstractly, enabling a deeper emotional connection with the subject matter.

Emotional Impact and Storytelling Through Tones

One of the most compelling reasons photographers choose monochrome over full-color photography lies in its emotional potential. Each hue carries psychological and cultural connotations. For example, images rendered in blue tones might evoke tranquility, melancholy, or introspection, while warmer hues such as sepia or amber can suggest warmth, memory, or timelessness. The singular color approach not only influences how an image feels but also how it is interpreted by the viewer.

Monochrome photographs often exhibit a dreamlike quality, enabling them to transcend realism and move into the realm of interpretation. By stripping the scene of multiple hues, photographers leave room for nuance and imagination. It’s a style that invites reflection, because its minimalism forces us to focus on subject, light direction, composition, and emotional intent.

A monochromatic image can be used to intensify mood or create cohesion within a photographic series. In genres such as fine art, portrait, architecture, and conceptual photography, monochrome can unify disparate elements and generate a powerful visual identity. For instance, a portrait with skin tones expressed entirely in soft shades of gold and brown can appear more timeless and intimate than a traditional color photo.

Another benefit is how effectively monochrome isolates and highlights patterns, shapes, and repetitions within the frame. Without the presence of diverse color distractions, the viewer becomes more attuned to rhythm and form. This quality is particularly valuable in architectural photography, where the design of structures and lines often carries more weight than their color.

Techniques and Contexts for Creating Monochromatic Imagery

Monochrome photography can be achieved in two primary ways—capturing a naturally monochromatic scene in-camera or applying a single-hue treatment during post-processing. Both approaches offer their own creative advantages, depending on the photographer’s intent and environment.

In-camera monochrome photography relies on recognizing and composing scenes that naturally consist of one color family. Examples might include a field of yellow sunflowers at sunset, a landscape dominated by snowy whites and icy blues, or an industrial setting washed in concrete gray. Shooting these subjects under consistent lighting enhances the visual harmony of the single-color palette. Mastering this technique requires a well-trained eye to spot tonal subtleties and anticipate how colors translate under different lighting conditions.

Post-processing, on the other hand, allows for more artistic intervention. Digital software such as Lightroom and Photoshop enables photographers to convert full-color images into monochromatic works by manipulating hue, saturation, and luminance. In Lightroom, for example, the Split Toning panel can be used to assign a uniform color to both the shadows and highlights, effectively toning the image with a consistent hue. Photoshop offers additional control through gradient maps and selective color adjustments, which can target specific tonal regions for precise control over depth and intensity.

|

Related Catagories: |

When processing monochrome images, subtlety is crucial. Heavy-handed use of color grading can make an image feel artificial or gimmicky. The goal is to preserve the emotional tone and enhance compositional elements without overwhelming them. This is why most successful monochromatic photographs begin with a well-thought-out color image—ideally one with natural tonal harmony and strong contrast between light and dark areas.

The application of monochrome is not limited to artistic or abstract contexts. It is increasingly used in branding, product photography, and editorial work. Monochrome tones offer a clean and minimalistic visual impact that aligns with modern design aesthetics. In commercial settings, using a consistent monochrome palette can help focus attention on texture, detail, and material—making it a valuable strategy for high-end visual storytelling.

Origins of Monochrome Photography: Chemical Innovation and Artistic Expression

The roots of monochrome photography can be traced to the very birth of the photographic medium itself. In the 19th century, long before color photography was technically feasible, monochrome was not simply a stylistic choice—it was a necessity. Early photographic processes relied heavily on chemical reactions and available materials, which naturally produced images in single tones. These tones weren’t initially chosen for their aesthetic value but were byproducts of the substances used in developing photos. However, what began as a limitation gradually evolved into an art form, celebrated for its expressive potential and timeless quality.

One of the most historically significant methods of monochrome development is the sepia process. Originating in the 1850s, sepia toning involved replacing the traditional metallic silver in black and white prints with a silver sulfide compound, resulting in a characteristic warm brown color. This was not only visually appealing but also increased the longevity and archival stability of the image. Sepia prints were less prone to degradation and fading compared to their silver-based counterparts, which made them popular in portrait studios and for family keepsakes. The richness of sepia offered more than technical advantages—it lent a sense of softness, nostalgia, and humanity to images, which black and white alone sometimes lacked.

Parallel to sepia, another monochromatic method was taking shape—cyanotype. Developed in 1842 by English scientist Sir John Herschel, the cyanotype process involved coating a surface with a solution of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. When exposed to ultraviolet light, the chemicals reacted to form a stable blue pigment known as Prussian blue. The result was a deep, vivid blue image on a white background. While less versatile than other photographic techniques, cyanotype had its own distinctive appeal. It became widely used in scientific documentation, particularly by botanist Anna Atkins, who famously used cyanotypes to publish the first book of photographic images featuring algae and ferns. Cyanotypes also found their way into engineering and architecture, giving birth to the term “blueprint.”

Cultural Significance and Visual Legacy of Sepia and Cyanotype

Over time, sepia and cyanotype moved beyond their utilitarian roots and entered the domain of fine art and cultural memory. Sepia images, often associated with antique portraits and early documentary work, have become symbols of heritage and historical reflection. The tonal warmth of sepia conveys a sense of age and authenticity, often used today to invoke feelings of reminiscence, antiquity, or familial legacy. In modern storytelling, applying a sepia tone to an image often serves as a visual cue to the past, anchoring the viewer in a specific emotional or historical context.

Cyanotype, in contrast, evokes a different kind of memory—less personal and more structural or archival. Its intense blue hues convey clarity, order, and methodical design, which explains its long-standing association with blueprints and scientific renderings. While not commonly used for portraiture, cyanotype’s graphic qualities have made it a staple in experimental and alternative photographic circles. Contemporary artists often return to cyanotype when exploring themes of nature, abstraction, or nostalgia through a cooler and more conceptual visual lens.

What makes both of these processes so enduring is their ability to transcend their chemical origins and take on symbolic roles. Sepia has come to represent warmth and sentiment, while cyanotype speaks of invention, knowledge, and precision. Despite their differences, both continue to be respected for their unique tonal signatures and historical importance in the evolution of photographic art.

Sepia and Cyanotype in the Digital Age: Emulation and Innovation

In today’s digital era, monochrome photography has been revitalized through software emulation. Sepia and cyanotype effects are now easily replicable using digital tools like Adobe Lightroom, Photoshop, and dedicated filter applications. While the modern versions lack the tactile experience and chemical nuance of the original processes, they provide accessible ways for photographers to pay homage to the aesthetic qualities of historical techniques.

Digital sepia toning allows photographers to add warmth and softness to modern portraits or travel photos. The subtle gradient from light tan to deep brown enhances skin tones and imparts a classical character to the image. The sepia filter is often used in storytelling, fine art, and lifestyle photography to create continuity between contemporary visuals and historical narratives.

Digital cyanotype, on the other hand, is often used in design-forward and conceptual photography. Its cool, electric blue tone contrasts well with strong whites and can create dramatic silhouettes and botanical impressions. Modern cyanotype effects are not limited to the color blue but can be manipulated through split toning or gradient overlays to achieve various creative results. Some digital artists even mimic the original cyanotype process more closely by photographing real botanical prints against stark backgrounds and digitally adding the iron-blue hue.

Moreover, the digital realm has allowed for the hybridization of these historical processes with modern concepts. Photographers often blend sepia or cyanotype tones with double exposures, compositing, and textures to create dreamlike visuals that nod to tradition while pushing the boundaries of current aesthetic norms. This intersection between the old and the new is a testament to the ongoing relevance of monochrome photography in artistic exploration.

As interest in vintage aesthetics continues to grow, the use of sepia and cyanotype emulation has become a popular tool for social media influencers, editorial photographers, and content creators. With a single filter, an image can be transformed into a piece that resonates with a different era, evoking emotional engagement through nostalgia and visual storytelling.

Sepia and Cyanotype as Living Legacies

The enduring appeal of sepia and cyanotype lies in their capacity to communicate across time. What began as practical developments in the early history of photography have become cherished artistic tools. Both processes contributed not only to technical innovation but also to the shaping of visual language. They helped define how we remember the past, how we interpret archival images, and how we connect emotionally with photographs.

Today, even with advanced digital cameras, color correction tools, and editing software, photographers continue to revisit these monochrome methods—not just for stylistic flair, but for what they represent. Sepia is more than just a warm tone; it is a symbol of memory and humanity. Cyanotype is more than a striking blue hue; it is a nod to science, exploration, and artistic clarity.

Photographers, artists, and visual storytellers benefit from understanding the origins and emotional resonance of these techniques. By studying their historical use and applying them mindfully in modern contexts, one gains access to a richer, more nuanced visual vocabulary. Whether through traditional chemical processes or contemporary digital simulations, sepia and cyanotype remain powerful tools for crafting meaningful imagery.

Monochrome photography is not simply a stylistic throwback; it is a timeless medium of expression. Sepia and cyanotype, as specific branches of this tradition, continue to offer photographers a way to merge technique, history, and emotion into a single cohesive frame—proving that even in a world dominated by vibrant color, there is enduring beauty in the discipline of tone.

The Role of Color Theory in Crafting Dynamic Monochrome Imagery

Monochrome photography may appear visually simple, but its execution requires a nuanced understanding of light, form, and especially color theory. While the term “monochrome” suggests a single color, it doesn’t equate to visual uniformity. A successful monochrome image leverages the full tonal range of a color—from luminous tints to deep shades—to create a compelling visual narrative. Understanding how hues transform across brightness and saturation levels helps photographers produce images that are expressive, rich, and dimensional.

Color theory plays an essential role in elevating monochromatic photography beyond a flat, one-dimensional look. By dissecting the components of any given hue and applying them with intention, photographers can orchestrate compositions that are both cohesive and visually intricate. Whether capturing landscapes, still life, architecture, or portraits, the ability to manipulate and recognize tonal diversity within a single color family is a critical skill for anyone exploring this creative style.

Breaking Down the Color Wheel: Hue, Tint, Tone, and Shade

A standard color wheel is a circular diagram used by artists and designers to visualize the relationships between colors. In monochrome photography, it becomes a tool for understanding the full expression of a single hue. At the outer edge of the wheel, colors appear in their purest form—these are known as hues. As you move inward, each hue transitions through variations known as tints, tones, and shades.

Tints are created by adding white to a hue, producing lighter versions that still retain the essence of the original color. In photographic terms, these often appear as highlights or brighter areas that catch more light. Tones result from mixing a hue with gray, offering a middle ground with subdued saturation. Shades are formed by adding black to the base hue, yielding darker, more dramatic values that typically represent shadowed or recessed areas in an image.

When applied to photography, this breakdown helps guide how light interacts with your subject. Consider a close-up of green moss under dappled sunlight. The parts directly illuminated by sun appear as vibrant tints, while shaded areas become deep forest green shades. The midrange, where light transitions more gradually, represents the tone. Capturing this entire spectrum within one frame turns a seemingly simple image into a dynamic composition full of visual texture and atmospheric depth.

Understanding this concept also allows for greater precision in post-processing. Photographers using tools like Lightroom or Photoshop can enhance monochrome images by selectively adjusting the luminance of specific tonal bands within a hue, rather than applying global adjustments that flatten contrast and detail.

Applying Tonal Variation in Monochrome Photography

Once a photographer understands the tonal potential of a single hue, the next step is applying that knowledge to create intentional, well-balanced compositions. In practical terms, this means seeking scenes or framing subjects that exhibit inherent contrast within one color family.

Take, for example, a wide-angle landscape where golden wheat fields stretch into the horizon. If shot during golden hour, the image naturally contains tints where the light strikes the tips of the crops, neutral tones in evenly lit areas, and darker shades where the stalks cluster in shadow. By carefully exposing and composing the scene to preserve these distinctions, the photographer ensures a multidimensional image that still adheres to a single hue.

In architecture, a monochrome image of a red brick building on an overcast day can similarly demonstrate tonal variation. The weather-softened daylight minimizes harsh highlights, allowing for a full spectrum of red-based tones to emerge—from salmon-tinted bricks reflecting more light, to burgundy and maroon shadows in recesses and grout lines. Shooting in RAW allows for further enhancement of these tones in post-production, where selective contrast and clarity adjustments can bring out subtle shifts within the monochrome palette.

Beyond capture, this technique is especially valuable in black and white photography, where color information is removed entirely but replaced with luminance variations. A deep understanding of how each color maps to gray is vital. For example, a scene with bright yellow and dark blue elements might appear as mid-gray and nearly black in a black and white conversion. Knowing this allows the photographer to predict how colors translate into monochrome and make compositional decisions accordingly.

Emotional Resonance and Visual Hierarchy Within Tonal Ranges

Beyond aesthetics, tonal range within a single color can influence the emotional tone and narrative strength of a photograph. Light tints often convey airiness, optimism, or calm. Midtones offer stability and neutrality, often anchoring the image visually. Deep shades, meanwhile, add gravity, mystery, or even melancholy. Using these tonal zones strategically allows photographers to guide the viewer’s emotional response without ever shifting hue.

In portraiture, for example, working within a monochrome brown palette can create a vintage or timeless effect. Using softer tints on the subject’s face and hair adds gentleness and approachability, while allowing the deeper tones of clothing or background elements to frame the subject enhances focus and visual hierarchy. Similarly, a blue-toned monochrome portrait with cool lighting and shadowy background can produce a serene, introspective mood.

Establishing visual hierarchy using tonal control is another core principle in effective monochrome photography. By ensuring that your subject occupies a distinctly different tonal value than the background, you create separation and emphasis. If the entire image hovers within a narrow band of luminance, it may feel flat or undefined. Expanding that band—by allowing for contrast between tints and shades—adds drama and draws the eye to focal points.

Photographers must also be aware of how human perception responds to contrast. High-contrast areas naturally pull attention, while smoother gradients or low-contrast zones act as visual rest points. Understanding how your color’s full tonal range affects these perceptual behaviors will help you guide the viewer’s gaze more deliberately.

Building Depth and Harmony in Monochromatic Frames

Color theory is not just for painters and designers—it’s an invaluable framework for photographers, especially those working in monochrome. Mastering hue-based tonal variation gives you the ability to breathe life into an image that might otherwise appear flat or one-dimensional. Through thoughtful observation and application, you can extract remarkable complexity from the simplest of scenes.

|

Related Catagories: |

Whether you're shooting green forest foliage, rust-colored industrial textures, or a series of portraits rendered in soft lavender tones, the ability to identify and utilize the full tonal range within a hue will elevate your compositions from ordinary to exceptional. Tools like the color wheel, paired with a practiced eye for lighting and exposure, serve as essential instruments for unlocking the creative potential of monochrome photography.

Ultimately, color theory helps transform monochrome from a minimalist aesthetic into a powerful narrative device. It adds richness, depth, and emotional subtlety—all while remaining within the boundaries of a single hue. For photographers seeking to explore the full expressive range of tone and light, there is no better place to start than by understanding how a single color can reveal an entire world.

Embracing the Art of Monochrome Photography at Capture

Capturing monochrome photos directly through your camera rather than converting them in post-production adds an element of authenticity and precision to your visual storytelling. When you photograph monochrome scenes in real time, you interact directly with the color environment, lighting conditions, and subject matter in ways that help shape your composition from the very beginning. This deliberate approach encourages greater attention to detail and makes you more aware of how tone, hue, and light interact within the frame.

Unlike converting to black and white or applying digital filters later, capturing natural monochrome compositions requires patience, keen observation, and a strong understanding of how colors behave under different lighting scenarios. Rather than relying on software to simplify color, you're relying on the scene itself to provide tonal unity within a single color family. This method is particularly effective when shooting in conditions where color palettes are inherently limited—think early morning mist, golden-hour backlight, or uniformly colored environments like autumn forests or desert dunes.

The process demands a blend of technical skill and artistic vision. You must be prepared to make on-the-spot decisions about exposure, white balance, and composition while consciously evaluating the dominant hue. While the camera’s sensor captures full-color data (especially in RAW), your goal is to isolate and enhance one consistent color throughout the scene.

Identifying and Composing Natural Monochromatic Scenes

One of the biggest misconceptions about monochrome photography is that you need to artificially create the look. In reality, natural monochromatic scenes exist all around us. You simply have to train your eye to recognize them. These scenes don’t have to be single-colored in a literal sense, but rather should consist of elements that fall within the same hue family, varying only in saturation, brightness, and shadow depth.

Imagine walking down a fog-covered alley in the early morning hours. The air is thick with mist, softening every edge. The buildings, pavement, and distant streetlights all appear in subtle shades of gray. That scene, even without applying a black and white filter, is a perfect candidate for an in-camera monochrome photo. Its atmosphere is dictated by limited color, natural lighting, and a cohesive tonal palette.

In nature, deserts and forests offer abundant monochromatic potential. A sandy landscape photographed under golden-hour lighting yields a rich array of amber, caramel, and bronze tones. Likewise, a densely wooded area bathed in green light—caused by leaves filtering the sun—can create an image built entirely around green, with varying luminance throughout the scene. Water bodies under certain lighting can also display a harmonious blue spectrum, from light sky reflections to deep navy shadows beneath the surface.

When composing these scenes, simplify the frame. Eliminate elements that fall outside the dominant hue. This often means changing your shooting angle, zooming in, or waiting for moving subjects (like people or cars) to leave the frame. Position your subject to make full use of the lighting conditions. In monochrome photography, contrast and texture become far more important than they are in full-color compositions. Be mindful of where the light falls, how shadows form, and where tonal transitions help guide the viewer’s eye.

Technical Settings and In-Camera Tips for Monochrome Excellence

Achieving a strong monochrome photograph in-camera goes beyond composition. Your technical settings can significantly affect the final result, especially when dealing with subtle color shifts within a hue. One of the first considerations is the shooting format. Always capture in RAW format if your camera supports it. This ensures the highest dynamic range and preserves tonal data, even if you preview the image in monochrome mode on your LCD screen.

Many digital cameras have picture styles or picture profiles that include a monochrome or black and white option. Activating this mode gives you a monochrome preview on the display while still preserving full-color data in the RAW file. This hybrid approach lets you visualize the final result in the field, while keeping your editing options open later. Cameras from brands like Nikon, Canon, Fujifilm, and Sony offer different levels of monochrome simulation in their picture profiles, some with built-in toning options like sepia or blue for added stylistic flexibility.

Adjusting white balance also plays a crucial role. Though it's often overlooked in monochrome work, setting a custom white balance can help exaggerate certain tones or neutralize competing hues. For example, setting a warmer white balance can make subtle reds and yellows more pronounced, helping you craft an image that leans toward warm monochrome without additional editing. Conversely, a cooler balance may push blues and greens into the spotlight.

Metering and exposure are essential in monochrome photography because small changes in brightness levels can shift a color's perceived tone. Use spot metering or center-weighted metering to evaluate the area you want most balanced. In high-contrast lighting situations, deliberately underexposing or overexposing can emphasize textures or isolate highlight and shadow zones within your monochromatic range.

Another overlooked but powerful setting is the use of color filters. Physical lens filters—such as yellow, orange, or red filters—alter how your camera interprets certain colors, especially when capturing in black and white. Red filters, for instance, darken skies dramatically and make clouds pop, while yellow filters provide more subtle contrast enhancement. These tools are particularly useful in landscape and architectural photography.

The Creative Rewards of Monochrome Intentionality

Capturing monochrome photos in-camera may take more effort than applying a digital filter, but the results often feel more cohesive and authentic. You’re crafting an image from the ground up, choosing your light, subject, and settings with the express purpose of rendering a scene through the lens of one dominant color. This approach instills a deeper connection to your subject and cultivates creative discipline.

One of the key benefits of capturing monochrome at the moment of shooting is spontaneity with awareness. Rather than retroactively searching for meaning in a photograph, you're anticipating it through composition, lighting, and hue control. This forward-thinking technique improves not only your monochrome work but your overall photographic vision. It teaches you how to see potential in scenes that others might overlook—be it an overcast afternoon on a foggy pier or a lone tree against a snow-covered hill.

Moreover, capturing monochrome in-camera enhances your storytelling. Each hue communicates something unique. Greens can convey growth and calm, while reds suggest passion or intensity. Blues may evoke serenity or introspection, and sepia tones often recall history and sentiment. When you shoot with these tones in mind, your images gain not just visual unity but emotional coherence.

For those working on thematic series or personal projects, natural monochrome photography offers an accessible yet visually rich method for consistency. Whether you're documenting cityscapes, exploring minimalism, or experimenting with abstract patterns, creating a body of work around a single hue can amplify your message and draw your audience into a more immersive experience.

Using Lightroom to Create Monochrome Effects

For photographers who prefer post-production control, creating monochrome images in software is a straightforward process. Adobe Lightroom offers a powerful Split Toning panel that lets users independently set the tone for highlights and shadows. To create a unified monochromatic look, assign the same hue to both highlights and shadows while adjusting the saturation to achieve the desired depth. This method lets you customize the emotional tone of the image—cool tones evoke calm or melancholy, while warm tones suggest intimacy or nostalgia. However, this technique should be used with intent. Applying monochrome tints to images with already chaotic or competing colors can yield unconvincing results. The most compelling edits begin with a foundation of visual simplicity and color harmony, making the monochrome effect feel like a natural extension of the scene.

What Defines Black and White Photography?

Black and white photography, sometimes referred to as grayscale, is a specialized subset of monochrome that uses only neutral tones—ranging from deep blacks to brilliant whites, with various shades of gray in between. This style strips images of all color information, encouraging viewers to focus instead on light, contrast, composition, and form. One of the defining strengths of black and white photography is its ability to highlight texture and structure. Without the influence of color, the eye is drawn to other elements such as line, balance, and negative space. This makes it a popular choice for architectural photography, street photography, and portraiture. Moreover, black and white imagery is known for its emotive power. By eliminating color, the emotional message often becomes more poignant, and the story within the image takes center stage.

High-Contrast Imagery and Abstract Expression

Within black and white photography, there exists a subgenre of high-contrast imagery. These photographs often contain extreme darks and lights with little or no midtone presence. The resulting effect is stark and dramatic, often bordering on abstraction. Such photos work well in minimalistic compositions, where the absence of midrange grays creates tension and amplifies visual impact. A photo of jagged white lines on a black backdrop or deep shadows cast by a spotlight can be effective examples. This bold use of contrast forces viewers to consider shape and light as primary elements—ideal for conceptual or experimental photography.

Capturing in Black and White vs Converting in Post

Most modern cameras offer a built-in black and white shooting mode, often labeled as "monochrome." However, this setting usually applies only to JPEG files, which lack the full depth and flexibility of RAW captures. For optimal results, it's advisable to shoot in RAW format, even if your camera displays a monochrome preview. This ensures maximum image data is retained, allowing for precise control during post-processing. You can adjust contrast, curve profiles, and tonal balance with far more flexibility in post than if you capture a compressed black and white image in-camera. Many professional photographers choose to visualize a scene in black and white while shooting, even though they’re capturing it in full color. This hybrid approach offers the best of both worlds: creative foresight and editing freedom.

Understanding Grayscale and Digital Color Modes

Grayscale, while often synonymous with black and white, has a specific meaning in digital editing environments. In software like Adobe Photoshop, converting an image to grayscale changes its color mode, eliminating all chromatic data and retaining only brightness values. This method is considered destructive—meaning that once converted, the original color cannot be restored unless you saved a separate version. In contrast, non-destructive black and white conversions maintain the color data beneath the surface, allowing you to revert or adjust without loss. This makes non-destructive workflows ideal for flexible creative processes. Grayscale mode is frequently used in professional printing, where precise tonal control is critical and color shifts must be completely eliminated. It guarantees consistency from screen to print.

Which Should You Use: Monochrome or Black and White?

Choosing between monochrome and black and white photography depends on your intent. Monochrome allows for emotional depth through the dominance of a single hue, often creating dreamlike or moody atmospheres. It’s well-suited for fine art, conceptual pieces, or stylized commercial work. Black and white photography, on the other hand, distills your image to its compositional essence. It removes the interpretive layer of color entirely and invites the viewer to engage directly with the shapes, contrasts, and emotions present in the scene. Instead of viewing them as competing styles, treat them as complementary. One highlights color uniformity; the other celebrates the absence of color altogether. Both have the power to elevate an image—what matters is your creative vision and the story you aim to tell.

Final Reflections on Tonal Photography

Both monochrome and black and white photography serve as powerful tools for artistic exploration. Each method offers its own aesthetic strengths and narrative possibilities. By learning when and how to use each one, you give yourself more freedom to express your photographic voice. Experiment with natural monochromatic compositions—scenes dominated by a single hue under cohesive lighting. Explore black and white conversions in post-production to understand how light and form interact without the distraction of color. Above all, let your creative instincts guide you. Photography is, at its heart, a medium of interpretation. Whether through the silence of grayscale or the subtlety of a single hue, your images can speak volumes—one tone at a time.