In photography, orientation is a foundational choice that impacts how stories are told through images. Whether you frame a shot vertically or horizontally is more than just a camera tilt—it’s a deliberate decision that influences how subjects are perceived, how space is used, and how emotions are communicated.

The vertical (portrait) and horizontal (landscape) orientations each bring their own visual grammar. Choosing between the two depends on a mix of artistic vision, subject dimensions, emotional intent, and presentation context. This guide explores how to approach orientation thoughtfully and with purpose—blending technical awareness with creative expression.

A Historical Perspective: How Orientation Shaped the Art of Photography

The concept of orientation has existed in visual art long before photography was born. Early painters used tall panels for religious icons and horizontal canvases for expansive scenes. When photography emerged, these compositional conventions evolved into practical tools for capturing the human form or natural landscapes.

The first known photographic portrait, taken in 1839 by Robert Cornelius, was composed vertically—a fitting format for a solo figure. From that moment, the portrait orientation became closely linked to human-centered imagery.

Photographers like Julia Margaret Cameron used the vertical frame to emphasize the elegance and stature of her subjects. Meanwhile, pioneers such as William Henry Jackson and Carleton Watkins used the breadth of horizontal composition to express the majesty of the American West. Their panoramic landscapes, rich with detail and depth, are testaments to the power of the landscape format.

Later artists, including Edward Weston and Henri Cartier-Bresson, blurred the boundaries by embracing both orientations based on the needs of their subjects. Weston’s shell studies, for example, are often framed vertically to accentuate curvature and symmetry. Cartier-Bresson’s street photography danced between both formats, using orientation as a tool to enhance geometry and spontaneity.

In the contemporary world, photographers like Cindy Sherman, known for her staged self-portraits, favor vertical compositions to simulate classical portraiture and confront the viewer head-on. Others, like Wolfgang Tillmans and Bill Henson, lean into the spaciousness of the landscape frame to create immersive, almost cinematic atmospheres.

These examples illustrate a key truth: orientation is never arbitrary. It’s a compositional decision informed by intent, subject, and context.

Factors That Influence Orientation in Photography

While creative instincts often guide orientation choices, it’s helpful to recognize the underlying compositional factors that influence your decision. These include subject shape, narrative flow, visual emphasis, emotional tone, and display format. By mastering these principles, you can frame each photograph in a way that best supports your story.

Matching Orientation to Subject Form

One of the most intuitive yet often overlooked principles in photography is selecting an image orientation that harmonizes with the shape and nature of your subject. Choosing between vertical and horizontal framing isn't just about aesthetics—it's about resonance. The orientation of your photograph can either complement your subject or create tension, guiding the viewer's attention in subtle but powerful ways.

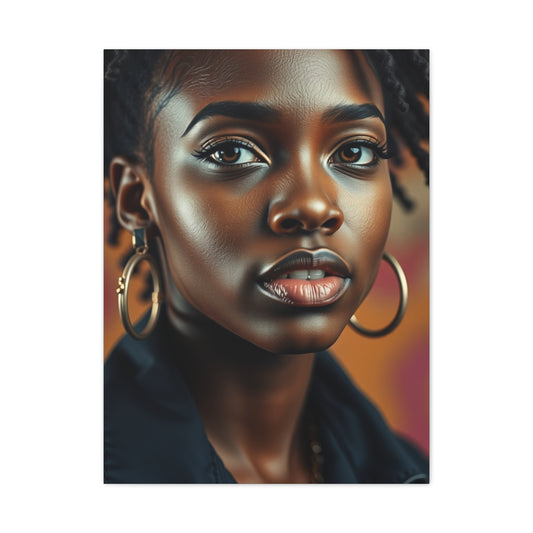

Tall, elongated subjects—like a solitary tree, a lighthouse, or a standing person—lend themselves naturally to portrait orientation. This vertical format stretches the frame upwards, making room for height and conveying a sense of stature, elegance, or intimacy. When a vertical subject is photographed within a vertical frame, it feels supported and well-anchored. There’s a graceful fluidity in the way the eye travels from bottom to top, mirroring the subject’s physical presence and creating a serene visual rhythm.

Portrait orientation also tends to feel more formal and contained. It directs the gaze inward, encouraging a personal connection with the subject. This is why it's so commonly used for human portraiture, editorial fashion, botanical studies, and architectural facades that rise skyward. The vertical framing reinforces linearity and focus, removing distractions and bringing the subject to the forefront.

In contrast, horizontal subjects—such as mountain ranges, seated groups of people, or elongated vehicles—demand space to stretch out. Landscape orientation accommodates this need, allowing you to compose with breadth and context. This orientation invites exploration. The eye moves more naturally from side to side, taking in layers of information, from foreground to background, or from left to right, echoing the way we read and scan visual material in most cultures.

When shooting landscapes or environmental portraits, the horizontal frame offers a sense of openness and movement. It provides spatial context and is particularly effective in scenes with leading lines, wide horizons, or multiple compositional elements. Group shots also benefit from landscape orientation, as it allows subjects to be framed evenly and avoids crowding.

Even with unconventional or abstract subjects, orientation plays a critical role in defining visual flow. Some subjects don’t adhere neatly to vertical or horizontal categories, yet their implied movement suggests a preferred orientation. A twisting vine, for example, may be better appreciated vertically if it grows upward, or horizontally if it meanders across a wall. The goal is to align the photograph’s frame with the dominant direction in which the viewer’s eye should move.

It’s also worth considering how negative space interacts with your subject’s form. Vertical orientation often reduces lateral breathing room, placing more emphasis on the central subject. This can create a strong emotional pull—ideal for conveying vulnerability, strength, or isolation. Meanwhile, horizontal compositions can use negative space to convey solitude, tranquility, or scale, especially in minimalist photography or conceptual art.

Certain genres tend to favor one orientation more than the other, not out of habit, but because of how well the format complements the subject’s essence. Wildlife photography often benefits from landscape framing, as animals in their environment are typically more active laterally than vertically. Food photography may use portrait orientation for plated dishes, especially in editorial layouts where vertical stacking allows room for copy or negative space.

Interior and architectural photographers often use both orientations to emphasize different aspects of a space. A vertical frame may highlight the soaring ceiling of a cathedral or the narrow depth of a hallway. A horizontal one might showcase a room’s spaciousness or capture multiple points of interest in a wide-open floor plan.

When working with human subjects, body language and posture also influence orientation. A model reclining on a surface might feel confined in a vertical crop, while standing poses often lose impact when squeezed into horizontal framing. Think of how the orientation of the frame either follows or fights the gesture, motion, or presence of the subject.

Orientation also affects energy and pacing. A vertical frame often feels still, composed, and deliberate. A horizontal frame tends to feel dynamic, relaxed, or open-ended. These psychological nuances should guide your choice as much as your subject’s literal shape.

At times, you may encounter a subject that could work in either orientation. In such cases, let your creative intent be the deciding factor. Ask yourself: what do I want the viewer to notice first? What emotional tone am I aiming for? What kind of movement do I want to evoke within the frame? Your answers will steer you toward a format that enhances your message and aligns with your artistic voice.

Practical considerations also play a role. Think about how your image will be displayed. If your final image is destined for a gallery wall with limited height, a landscape format might be more effective. If the image is going to be used on social media, portrait orientation often performs better on vertical phone screens. The same subject may look vastly different—and be received differently—based on where and how it's presented.

In commercial contexts, orientation can be shaped by branding guidelines or layout constraints. For print ads, editorial spreads, or digital banners, you might need to shoot with cropping in mind, ensuring that your composition works well in both formats. This adds complexity but also encourages versatility and awareness.

When shooting in the field, train yourself to see the same scene through both lenses. Rotate your camera and reframe the shot. How does the subject behave in each orientation? Does one version feel more emotionally charged? More spacious? More refined? With practice, you’ll begin to sense the right fit almost instinctively.

Ultimately, choosing the right orientation is not just about mechanics—it’s about storytelling. Every subject has a shape, a rhythm, and a presence. Your job as a photographer is to match that essence with a frame that honors it. Whether vertical or horizontal, your composition should feel like a natural extension of the subject’s character.

Orientation as an Artistic Translator

Orientation is far more than a technical aspect of photography—it’s a silent translator of form and mood. The way you frame your subject shapes not only what the viewer sees, but how they feel when they see it. Vertical and horizontal formats each carry visual language that either supports the subject’s expression or hinders it.

Matching the frame to the form allows your subject to resonate with clarity and purpose. When orientation flows in harmony with visual direction, your photo feels complete and intentional. When it contrasts, it creates tension—sometimes useful, sometimes confusing.

By staying attuned to the nuances of your subject—its size, posture, energy, and spatial demands—you elevate your creative control. Orientation becomes a compositional tool that goes beyond format. It becomes a way to align vision with impact.

So the next time you compose an image, pause and consider: does this frame echo the spirit of what I’m photographing? If it does, you’ll likely find that your work not only looks better—but speaks more clearly, too.

Using Orientation as a Cropping and Framing Tool

Orientation is one of the most understated yet impactful tools in a photographer’s creative arsenal. Beyond influencing composition, it functions as a framing device—a way to crop a scene in-camera and determine exactly how much visual information you present to your viewer. By switching between portrait and landscape formats, you control the image’s structure, rhythm, and emotional resonance.

Portrait orientation inherently restricts the horizontal field of view, bringing the viewer closer to the subject both physically and psychologically. It eliminates peripheral distractions, narrowing the viewer's attention onto the central figure or object. This vertical framing enhances intimacy and focus, especially when photographing people, tall objects, or anything meant to feel direct and personal. Whether you’re isolating a dancer mid-motion, capturing a single flower, or framing a tall structure, portrait format offers a clean, controlled composition that emphasizes linearity and form.

In contrast, landscape orientation creates space—literally and emotionally. It provides lateral breathing room, offering an open stage for subjects to interact with their surroundings. This format is especially effective in environmental portraiture, travel photography, or storytelling scenes where background elements add meaning. With a horizontal frame, the viewer’s eye is encouraged to move from left to right, scanning the environment and absorbing visual context. A wide-angle street shot or a serene coastal landscape thrives in this layout, where storytelling depends on the harmony between subject and setting.

Orientation also plays a crucial role in managing unwanted elements. Switching from landscape to portrait can crop out busy side areas, signage, or other visual noise. Conversely, moving from portrait to landscape might eliminate ceiling fixtures, wires, or awkward vertical gaps. Instead of relying solely on post-processing to remove distractions, orientation allows you to solve compositional problems before pressing the shutter.

This in-camera cropping method not only saves editing time but also helps retain image quality. By composing intentionally, you avoid unnecessary digital manipulation that could compromise resolution, sharpness, or aspect ratio. While cropping in post is sometimes necessary, capturing a shot with the ideal orientation from the start shows mastery of spatial awareness.

Orientation also directly influences how balance and emphasis are handled in the image. In portrait format, subjects often take up more vertical space and feel anchored, especially when aligned with the rule of thirds or centered for symmetry. This creates a visual pathway from bottom to top, ideal for standing figures, symmetrical architecture, or vertical lines that draw the eye upward.

Landscape orientation, by contrast, shifts that balance sideways. The weight of the composition is distributed from side to side, and elements can be arranged in sequences across the frame. This makes it easier to incorporate secondary points of interest or leading lines that guide the eye. A pedestrian walking along a wall, a car crossing a bridge, or a dog running through a park—all these narratives benefit from the storytelling capacity of a wider frame.

Framing with orientation also allows you to manipulate proximity and tension. A close-up face in portrait orientation might feel emotionally intense and intimate, while the same subject photographed in landscape format—with surrounding space—can evoke solitude or contemplation. Each orientation holds its own mood, and when paired with subject matter, lighting, and composition, the frame becomes a powerful emotional conductor.

Orientation also has strong implications for how light is captured. In portrait mode, directional light often follows the vertical length of a subject, creating soft gradients that wrap from forehead to chin or from shoulders to waist. Landscape orientation, especially in natural light, captures broader shifts in exposure across a scene—from sun-drenched fields to shadowed treelines or side-lit interiors. The interaction between light and framing direction influences not just clarity but atmosphere.

In practical terms, orientation choices can be governed by where and how the image will be used. Portrait-oriented photos perform better on smartphones and vertical digital displays, making them ideal for social media content, blogs, or mobile advertising. Landscape images, on the other hand, are more suitable for web banners, YouTube thumbnails, slideshow presentations, and widescreen portfolios. Understanding the context in which your image will appear helps you make informed framing decisions that support your goals—whether artistic or commercial.

Photographers creating a visual series can use orientation to bring structure or contrast. Consistent orientation provides cohesion, especially in galleries or photobooks. However, mixing portrait and landscape formats can introduce dynamic variety, keeping the viewer engaged through rhythm and pacing. Each choice should serve your narrative rather than detract from it.

In terms of editing, orientation remains a versatile asset. A horizontal image can be cropped into a vertical panel to emphasize a detail, isolate a gesture, or shift focus to a singular object. Similarly, a vertical photo can be reimagined as a square or widescreen format to change tone or composition. While these adjustments are valuable in post-processing, the strongest compositions begin with deliberate orientation at the time of capture.

Mastering orientation as a framing tool is about training your eye to anticipate how the subject, space, and light will interact within the frame. It’s a constant exercise in awareness: asking yourself what you want to emphasize, what to exclude, and how best to arrange the visual hierarchy. As you gain experience, switching orientations becomes less about experimentation and more about expression—a natural extension of your photographic voice.

Orientation as a Narrative Shaper

Orientation doesn’t merely define the shape of your image—it defines how the viewer reads it. A well-chosen frame guides the eye, sets the mood, and subtly influences emotional engagement. Used wisely, orientation shapes the story by directing what gets seen and what stays hidden.

In vertical frames, the story often lies in the details: a gentle tilt of the head, the texture of fabric, the narrow shaft of light spilling across a room. These images draw you in. They’re introspective, contained, and personal.

In horizontal frames, the story unfolds across a larger field. It may involve multiple characters, deeper context, or broader themes. It’s about interactions—between people, between elements, between light and land. The landscape format makes room for complexity, for movement, for exploration.

When orientation is used as a framing tool, it empowers photographers to be not just image-makers, but storytellers. You’re not simply capturing what’s in front of you—you’re curating the visual experience. Each edge of the frame becomes a choice. Each boundary becomes intentional. And each orientation becomes an act of visual storytelling.

So next time you frame your shot, consider not only the subject but the story. Let your orientation enhance what you’re trying to say, and you’ll discover how much power truly lies in the edges of the frame.

Influencing Subject Emphasis Through Framing Direction

The orientation of a photograph does more than frame a subject—it directs the viewer’s attention, dictates visual priority, and alters the emotional undercurrent of the entire image. Framing direction becomes a silent guide that tells the audience where to look, how long to linger, and what to emotionally absorb. Whether you choose a horizontal (landscape) or vertical (portrait) format, each direction comes with its own visual grammar and storytelling power.

Horizontal framing, often associated with the landscape format, invites the viewer into a broad, expansive field of vision. The eye naturally travels from left to right—a motion that mirrors reading patterns in many cultures—creating a comfortable and immersive visual flow. This orientation suits subjects that require spatial breathing room or environmental context. It is ideal for wide scenes, multi-element compositions, or narratives that unfold across space, such as street scenes, open landscapes, or candid interactions.

In a landscape frame, the subject becomes part of a larger visual ecosystem. The emphasis is less on isolation and more on connection—between figures and background, between light and shadow, between stillness and motion. The added width provides opportunities to introduce secondary subjects or visual cues that enrich the central narrative. For example, placing a person at one end of the frame and allowing negative space on the other side can evoke themes of solitude, anticipation, or balance.

In contrast, vertical framing narrows the focus. A portrait-oriented photograph creates an upward or downward movement, channeling the eye along a single dominant line. This framing naturally draws attention to posture, symmetry, and vertical features such as trees, columns, or human figures. It conveys formality and elevation. In portraiture, especially full-body or fashion shoots, vertical orientation accentuates length and body language, adding elegance or strength depending on the pose.

The vertical frame compresses space. It reduces environmental distractions and simplifies the narrative, making the subject feel more isolated, powerful, or vulnerable depending on the context. This can heighten the emotional impact of the image. A lone subject framed vertically against a minimal background often feels more intense, confronting the viewer with raw presence.

Understanding how framing direction affects subject emphasis allows photographers to play with perception and emotional tone. A subject that appears ordinary in landscape orientation can become monumental when reframed vertically. Consider a tree in a park—casual and pleasant in horizontal format, yet towering and poetic in portrait orientation. The change alters not only the composition but the very essence of what the image communicates.

Similarly, a subject photographed horizontally may feel more integrated and grounded. A model posed in a relaxed stance within a wide room might lose that sense of ease when squeezed into a vertical frame. In this case, the horizontal orientation adds atmosphere and mood, allowing the surroundings to inform the interpretation of the subject’s presence.

One of the most impactful techniques for creating visual drama is to use orientation that contrasts with the natural flow of the subject. For instance, photographing a horizontally dominant subject—like a car or a bridge—in vertical format introduces tension. The frame feels tight, restricted, almost claustrophobic, and this dissonance forces the viewer to engage more actively with the image. It becomes less about passive consumption and more about psychological interaction.

This compositional tension can be particularly useful in editorial or conceptual photography where you aim to challenge norms and evoke emotional response. A dancer mid-leap framed vertically enhances the grace and arc of the movement. But that same dancer shot horizontally—especially with space to “move into”—can evoke a sense of anticipation or flight. The choice depends entirely on the mood you wish to convey.

Orientation also plays a role in the hierarchy of elements within the frame. A vertical composition might give prominence to a subject’s facial expression, elongate shadows, or emphasize vertical lines like staircases or flowing garments. A horizontal layout can highlight alignment, repetition, or symmetry across a wider visual field. Knowing how to shift visual emphasis allows for intentional storytelling, especially in scenes where multiple compositional layers are at play.

In portraits, orientation becomes especially sensitive to the subject’s posture and gaze. A vertical image frames the human form more naturally, offering a head-to-toe view that emphasizes elegance and posture. A horizontal portrait, on the other hand, gives space for gesture—perhaps a turned shoulder, a seated posture, or an expressive hand. It introduces storytelling elements that a tight vertical crop might eliminate.

Beyond aesthetics, framing direction interacts with light, shadow, and color in unique ways. Vertical compositions may showcase vertical gradients of light—ideal for side-lit portraits or shafts of sunlight. Horizontal frames, with their extended width, are excellent for capturing shifts in tone across the sky, horizon, or surfaces like water or glass.

As you refine your photographic vision, you’ll find that the orientation of your frame becomes part of your visual language. It’s not just a mechanical choice, but a narrative one—framing direction acts like punctuation in a visual sentence. A horizontal frame might feel like an ellipsis… open and expansive. A vertical frame may be an exclamation mark—strong, precise, and focused.

Framing Direction as a Compositional Device

When used thoughtfully, framing direction becomes more than a compositional tool—it becomes a narrative device. The choice between landscape and portrait orientation influences not just what’s in the frame, but how that content is consumed emotionally and psychologically.

Photographers who experiment with both orientations gain access to dual perspectives. They learn how to express intimacy with vertical framing and how to tell expansive stories with horizontal ones. Each orientation lends itself to a particular rhythm, and part of mastering visual storytelling is knowing which rhythm best suits the subject at hand.

For example, documentary photographers often work in landscape orientation because it provides context—capturing the subject and their surroundings together. This orientation supports visual depth, emotional distance, and broader narrative arcs. Conversely, portrait photographers frequently rely on vertical frames to emphasize connection, facial expressions, and bodily posture—focusing more on emotion than setting.

The most dynamic photographers, however, are those who understand that these aren’t rigid rules but creative tools. They might photograph a full-body subject in a landscape orientation to introduce tension or isolate a subject in a vertical frame to spotlight psychological space.

Framing direction can also be used to create series or visual contrasts within a single project. A collection of vertical portraits interspersed with horizontal environmental shots adds rhythm and variation. It’s a way of guiding the viewer through visual space, offering moments of closeness and moments of distance.

Ultimately, the orientation you choose should feel purposeful. It should echo your intent, amplify your subject, and frame your message with clarity. When used with care, framing direction doesn’t just house the subject—it elevates it.

Conveying Mood Through Orientation

The orientation of a photograph is more than just a framing decision—it’s a psychological instrument that directly shapes the viewer’s emotional response. Whether the camera is turned vertically or horizontally, that choice inherently defines the mood and atmosphere of the image. Orientation sets the tone long before the viewer has had time to consciously analyze the subject, lighting, or composition.

Horizontal orientation, widely known as landscape format, often communicates a sense of calm, space, and continuity. This framing is harmonious with the way we naturally observe the world—from sweeping horizons and ocean vistas to group interactions and city streets. The landscape layout invites the eye to travel across the width of the image, absorbing multiple layers of visual information. As the viewer scans the frame, they experience the image gradually, often interpreting it as peaceful or contemplative.

This tranquil quality is why horizontal framing is favored in genres such as nature photography, documentary work, and architectural scenes. A wide river cutting across a valley, a quiet street with long shadows, or a couple sitting on a bench beneath a vast sky all feel introspective and unhurried when captured in landscape orientation. The extra space at the edges fosters a sense of openness, allowing the subject to breathe and suggesting that the story continues beyond the edges of the frame.

Additionally, horizontal framing can emphasize rhythm and repetition. A series of windows on a building, the alignment of trees along a road, or waves rolling into shore all benefit from the lateral flow of a landscape composition. The repeated patterns reinforce calmness and invite the viewer into a visual meditation.

Vertical orientation, on the other hand, offers a very different kind of mood. Known as portrait format, this direction inherently feels more controlled, direct, and often more emotionally charged. It introduces structure by restricting the horizontal space and emphasizing height and depth. Because vertical framing directs the eye from top to bottom—or bottom to top—it encourages a more linear and introspective viewing experience.

Portrait orientation is ideal for subjects that require attention to posture, expression, or symmetry. A tall building stretching into the sky, a person gazing out a window, or a single column of light cutting through darkness all gain a sense of grandeur, strength, or introspection when framed vertically. The narrower field forces the viewer to focus, reducing peripheral distractions and intensifying the emotional resonance.

This format lends itself especially well to editorial, fashion, and fine art portraiture. It can be formal and elegant or stark and powerful, depending on how it's paired with light, contrast, and composition. In many cases, vertical framing brings a sense of confrontation—the viewer is placed face-to-face with the subject, unable to look away. This directness is what gives portrait orientation its emotional weight.

The impact of mood through orientation extends further when it breaks expectations. Photographers who challenge traditional framing conventions often discover fresh emotional textures. Capturing a wide landscape in portrait format compresses the expanse, emphasizing verticality and intimacy. The result may feel constrained or monumental, depending on the composition and subject. A towering forest shot in portrait mode, for instance, can evoke the feeling of being engulfed by nature, creating a sensation of awe or insignificance.

Conversely, shooting a traditionally vertical subject in landscape orientation can defy the viewer’s assumptions. A full-body portrait taken horizontally—perhaps with negative space on either side—can feel cinematic, relaxed, or even surreal. This approach introduces narrative ambiguity and offers space for the viewer to interpret mood beyond the subject’s immediate presence.

Breaking the mold with orientation also allows for psychological storytelling. A lone figure photographed in vertical format against a tight frame may evoke isolation or tension. The same subject framed horizontally with generous negative space could suggest freedom, loneliness, or serenity—depending on the supporting visual elements like light and color.

Orientation can also mirror human emotions. Vertical frames may represent ambition, control, or introspection. Horizontal frames often suggest relaxation, openness, or connection. When used with intention, orientation becomes a visual metaphor that enhances the subtext of your image.

Mood is also reinforced through the relationship between orientation and lighting. Vertical images often benefit from directional lighting that enhances the length of the frame—casting long shadows or highlighting form in a top-down or side-lit pattern. This technique adds drama and depth, making the vertical frame even more expressive. Meanwhile, horizontal images with ambient or even lighting often create a tranquil, painterly effect. The light feels spread evenly across the frame, softening contrast and inviting the viewer to dwell in the serenity of the scene.

Even in abstract or conceptual photography, orientation influences perception. Vertical lines tend to feel strong and assertive, while horizontal lines are viewed as calm and grounded. Compositions that use strong verticals in portrait orientation double down on intensity, while horizontal lines in landscape frames reinforce a sense of equilibrium.

The use of orientation to convey mood also extends to color theory and texture. A vertical frame might highlight cool tones and smooth surfaces to evoke stillness or melancholy. A horizontal image filled with warm hues and organic textures might suggest warmth, nostalgia, or emotional depth. By pairing orientation with complementary visual elements, the emotional tone of an image becomes more layered and cohesive.

Ultimately, the orientation of your image should support—not fight—your intended mood. If your goal is to inspire reflection, portrait framing may offer the focus needed. If your aim is to present a moment of peace, landscape orientation provides the serenity and spatial clarity. The key is to remain aware of how directional framing shapes not just what is seen, but how it feels.

Framing Mood with Purpose and Flexibility

The relationship between orientation and emotional tone is a creative dialogue—a subtle but powerful conversation between photographer and viewer. Choosing between portrait and landscape formats is not a mechanical act but a mood-setting decision that shapes the image’s voice and emotional cadence.

A photograph’s orientation tells the viewer how to feel before they know what to feel. It directs their gaze, influences the pace at which they experience the image, and colors the emotional backdrop of the subject. Horizontal framing often soothes; vertical framing often commands. But these are not rigid laws—they are expressive tools waiting to be molded to your artistic vision.

The most evocative photographers understand this interplay and use orientation as part of their narrative toolkit. They recognize when to align with visual expectations and when to subvert them, turning the frame into an active agent of mood. They choose orientation not just to fit the subject, but to elevate it—ensuring every image resonates with the feeling it was meant to convey.

By learning to see orientation as a mood-shaping element, you begin to approach photography with greater intentionality. You don't just frame what you see—you frame how you want others to feel. And in doing so, you create not just images, but experiences.

Planning for Print, Display, and Digital Sharing

Orientation also plays a critical role in how your image is experienced in physical or digital spaces. Whether you're planning to exhibit your work in a gallery, publish it in a book, or share it online, the chosen format will influence the viewer's engagement.

In print, wall space often dictates orientation preferences. Portrait images work well in tall, narrow spaces, while landscape images suit wider surfaces. If you're displaying a series of photos, maintaining consistent orientation can create visual harmony. Mixing orientations, on the other hand, introduces dynamic variation and energy—useful in editorial layouts or art installations.

In digital environments, orientation affects interaction. Social media platforms like Instagram favor vertical imagery for mobile engagement. Portrait-oriented photos dominate the screen, attracting more attention and generating stronger emotional connection in mobile scrolling contexts.

For websites and desktop presentations, horizontal formats may offer better screen coverage and immersive appeal. Consider your target audience, delivery platform, and viewing conditions when selecting your frame orientation for digital content.

Knowing When to Break the Rules

Rules and recommendations exist to help you achieve visual harmony, but some of the most compelling photographs result from thoughtful defiance. Choosing an unconventional orientation can challenge expectations, evoke surprise, or spark curiosity.

Try photographing a sweeping landscape in portrait format to accentuate verticality and lead the eye skyward. Capture a full-length portrait in landscape orientation to emphasize negative space or surrounding context. These unexpected choices create tension, depth, and originality.

Experimentation is essential. It teaches you when orientation supports a subject—and when opposing it offers a stronger visual narrative. Through trial and analysis, you’ll develop your intuition for what feels right for a given moment.

Conclusion: Orientation as a Storytelling Tool

Orientation in photography is not simply about aligning the camera vertically or horizontally. It’s about composing with purpose, emphasizing with clarity, and evoking emotion through format. The direction you frame your subject becomes an extension of your creative language.

By thoughtfully choosing between portrait and landscape orientations, you sharpen your ability to express mood, clarify message, and connect with your audience. Whether you aim for intimacy or grandeur, precision or fluidity, the right orientation allows your photograph to speak with authenticity and impact.

Before you press the shutter, take a moment to reflect: what’s the feeling you want to convey? What perspective tells the truest version of your story? The orientation you choose might just be the detail that transforms a good image into a memorable one.