Claude Monet, widely regarded as the father of the Impressionist movement, revolutionized the way the world perceived art. Born in 1840 in Paris, Monet demonstrated an early passion for capturing the natural world, blending keen observation with an innovative brush technique that emphasized light, color, and atmosphere over fine detail. This approach broke away from the rigid formalism of the 19th-century academic painting tradition, paving the way for a new artistic language focused on perception and fleeting moments.

Monet’s work is best understood through his fascination with nature, particularly gardens, rivers, and urban landscapes. Unlike his contemporaries, who often prioritized historical or religious subjects, Monet sought inspiration in the everyday beauty of his surroundings. He experimented with the effects of changing light and seasons, meticulously studying how colors and shadows transformed across different times of day. His dedication to plein air painting—working outdoors rather than in a studio—allowed him to capture the dynamic interaction of light and landscape with unprecedented vibrancy.

One of the defining characteristics of Monet’s technique is the visible, almost tactile brushstroke. Rather than striving for smooth surfaces, he applied short, broken strokes to convey movement, texture, and the shimmering quality of light. This method allowed the observer to engage actively with the painting, piecing together the scene through perception rather than explicit detail. The result was a series of canvases that seemed to vibrate with energy and emotion, reflecting not just the scene itself but the artist’s sensory experience of it.

Among his most celebrated works, the water lily series stands as a pinnacle of Monet’s exploration of nature and abstraction. Inspired by his meticulously designed garden in Giverny, these paintings feature tranquil ponds adorned with floating lilies, often punctuated by the iconic Japanese bridge. Monet painted these scenes repeatedly over decades, experimenting with color, composition, and the reflection of light on water. Each iteration captures a unique mood, whether it be the serenity of a quiet morning or the subtle shifts of sunset. These works exemplify his ability to balance realism with a dreamlike quality, allowing viewers to lose themselves in the reflective, almost meditative world of the pond.

Monet’s fascination with urban landscapes is equally compelling. His series on the Houses of Parliament in London, for instance, demonstrates his skill in portraying atmospheric conditions such as fog, mist, and varying sunlight. Over 100 canvases depict this iconic structure under different weather and light, emphasizing the ephemeral beauty of the city. Similarly, his studies of the Waterloo Bridge highlight the interplay of industrial haze and natural light, capturing both the grandeur of architecture and the subtle emotional resonance of the environment. These urban works reveal Monet’s keen sensitivity to light and atmosphere, extending his naturalistic vision into the bustling, modern world.

One of Monet’s earliest works to define the Impressionist movement is “Impression, Sunrise,” completed in 1872. This painting, depicting the port of Le Havre at dawn, gave the movement its name and exemplified the shift from traditional representation to capturing transient impressions. The soft, fluid application of paint conveys the early morning haze, the glimmering reflection on water, and the delicate interplay of sky and sea. Unlike the precise realism valued by academic standards, the work evokes feeling and perception, inviting the viewer to experience the moment rather than simply observe it. This radical approach influenced generations of artists and cemented Monet’s status as a transformative figure in art history.

Monet also explored more intimate, personal scenes, often reflecting his family life and surroundings. In works such as “Woman with a Parasol,” he captures his wife and child in a breezy, sunlit field, emphasizing spontaneity and natural movement. These paintings highlight his sensitivity to human presence within landscapes, blending portraiture with environmental context. The lightheartedness and fluidity of these works offer a glimpse into Monet’s personal world, reflecting his affection for family and the joy he found in simple, everyday moments.

His series of grainstacks, painted in the 1890s, further demonstrates his fascination with seasonal and temporal changes. By capturing the same subject under different lighting conditions and atmospheric effects, Monet studied the nuances of shadow, reflection, and color modulation. These canvases illustrate the subtle variations of natural light, revealing how the environment itself transforms perception. The grainstack series exemplifies his commitment to observation and experimentation, showcasing his innovative approach to capturing the temporal dimension in visual art.

Monet’s time in Venice produced some of his most vibrant and colorful works. Paintings of San Giorgio Maggiore at dusk, for instance, depict the interplay of water, architecture, and evening light with vivid hues and bold compositions. Here, Monet blends his mastery of reflection and shadow with a heightened color palette, demonstrating his adaptability to different landscapes and lighting conditions. These works highlight the universality of his vision: whether in urban centers, rural countryside, or exotic locales, Monet’s eye consistently seeks the interaction between light, color, and form.

In addition to landscapes and cityscapes, Monet occasionally explored floral compositions, including sunflowers and irises. While not as famous as his water lilies, these pieces reveal his continued fascination with the effects of light and color on natural forms. In particular, his iris series demonstrates his sensitivity to subtle tonal variations, creating an ethereal, contemplative mood. These studies reinforce Monet’s overarching philosophy: art is not merely a representation of objects but an exploration of perception, light, and atmosphere.

Monet’s legacy is defined not just by the subjects he painted but by the methodology he pioneered. His insistence on capturing the transient, ever-changing qualities of light and environment reshaped the conventions of painting. By focusing on perception, movement, and sensory experience, he laid the foundation for Impressionism and influenced countless artists in modern and contemporary movements. His body of work, encompassing gardens, urban landscapes, intimate portraits, and floral studies, offers a comprehensive vision of how observation and emotion intertwine in the creation of art.

Understanding Monet’s paintings requires more than simply viewing them; it involves an immersion in his perceptual world. Each brushstroke, color choice, and compositional decision contributes to a holistic sensory experience. Through repeated subjects—whether water lilies, bridges, grainstacks, or cityscapes—Monet challenges viewers to notice subtle shifts in light, shadow, and atmosphere, inviting a contemplative engagement with the natural and constructed world alike. This approach underscores the enduring relevance of his work, as contemporary audiences continue to find inspiration and solace in the visual poetry he created.

Claude Monet’s work is often celebrated not just for its beauty but for the innovative approach it brought to painting. Across his career, Monet repeatedly returned to subjects, exploring them under varying light, weather, and seasons. These series demonstrate his fascination with the fleeting qualities of nature and urban life and offer a window into his meticulous observational skills. In this part, we examine some of Monet’s most iconic paintings, exploring the inspiration behind them, their visual qualities, and the enduring impact they have on art and culture.

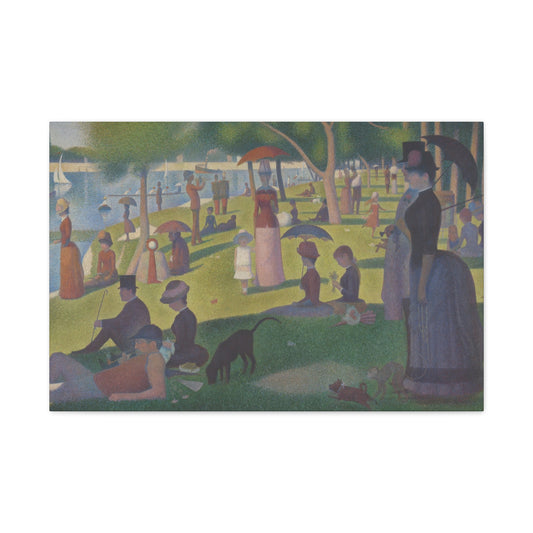

One of Monet’s most famous and enduring subjects was the water lily pond in his garden at Giverny. This collection of paintings, which he worked on intensively in the later years of his life, captures a tranquil yet vibrant environment where water, flora, and reflection coexist in perfect harmony. “Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge,” created in 1899, is emblematic of this series. The Japanese-inspired bridge, gracefully arching over the pond, serves as both a compositional anchor and a symbol of Eastern influence in Western art. Monet’s treatment of light in this painting is particularly remarkable: the surface of the water shimmers with reflected sky and foliage, creating a sense of depth and movement that draws the viewer into the scene. The cool, soothing color palette encourages contemplation, highlighting Monet’s ability to evoke emotion through color and form.

Another painting from the water lily series, completed in 1916, reflects Monet’s continued fascination with capturing subtle variations of light and atmosphere. Painted during the turmoil of World War I, this work serves as a peaceful counterpoint to the external chaos, emphasizing serenity and the restorative power of nature. Monet’s method involved layering delicate strokes and nuanced colors, giving each painting a sense of vibrancy and life. The water lilies themselves are more than mere botanical depictions; they function as a vehicle for exploring reflections, movement, and the interaction of color across water, making each piece simultaneously realistic and abstract.

Monet’s exploration of urban landscapes is equally compelling. His series depicting the Houses of Parliament in London captures the building under various lighting conditions, from hazy dawns to glowing sunsets. Over 100 canvases portray this iconic structure, demonstrating Monet’s fascination with fog, industrial atmosphere, and the effects of sunlight filtering through mist. Each painting presents a unique perspective on the same subject, revealing the subtle transformations of light and color over time. By focusing on the ephemeral qualities of the scene, Monet elevates the Houses of Parliament from a mere architectural subject to an exploration of atmospheric perception. The repetition of the subject in this series underscores Monet’s experimental approach, inviting viewers to consider how perspective and light shape the experience of place.

Similarly, Monet’s depictions of the Waterloo Bridge in London reveal his interest in the interplay between urban structure and environmental conditions. Created in the early 1900s, these works highlight the effects of fog and mist on perception. Monet often painted the same scene at different times of day, emphasizing the constantly changing qualities of light and atmosphere. The muted tones and soft blending of colors create a dreamlike quality, demonstrating his mastery of mood and subtle nuance. These paintings are particularly notable for their ability to capture industrial modernity without losing a sense of natural beauty, bridging the gap between human-made and natural environments.

“Impression, Sunrise,” painted in 1872, is perhaps Monet’s most historically significant work. Depicting the harbor of Le Havre at dawn, this painting is credited with giving the Impressionist movement its name. Monet’s brushwork here is loose and fluid, focusing on capturing the sensation of the scene rather than detailed accuracy. The rising sun glimmers across the water, partially obscured by morning mist, creating a luminous effect that defines the painting’s mood. This work exemplifies Monet’s revolutionary approach: by prioritizing perception and atmosphere over conventional realism, he challenged traditional standards of representation and influenced a generation of artists who followed.

Monet also explored intimate, personal scenes that reflect his life and family. In “Woman with a Parasol,” also known as “Madame Monet and Her Son,” he depicts his wife Camille and their young child on a breezy summer day. The painting conveys motion, light, and the ephemeral nature of a casual moment in a way that feels spontaneous yet carefully composed. The brushstrokes capture the movement of the wind through fabric and grass, creating a sense of vitality and immediacy. Unlike his urban and garden scenes, which often explore broader atmospheric effects, this painting emphasizes the interaction between human presence and environment, adding a layer of narrative intimacy to his oeuvre.

Monet’s grainstack series, completed in the 1890s and early 1900s, further demonstrates his obsession with light and time. Each canvas portrays a haystack at different times of day and during different seasons, highlighting how light transforms color and perception. Monet’s technique involved studying these variations in depth, returning repeatedly to the same subject under changing conditions. The results are a remarkable study in atmospheric effects, with each painting offering a distinct mood and palette. By repeating the subject in multiple variations, Monet emphasizes the transient nature of visual experience and the role of observation in artistic creation.

Monet’s fascination with Venice is also evident in works such as “San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk.” Here, the vibrant interplay of water, architecture, and fading light creates a composition rich in color and depth. Monet’s brushwork conveys both the solidity of the buildings and the ethereal quality of the reflective water, demonstrating his ability to merge structure with fluidity. The sunset’s warm glow contrasts with the cooler tones of the water, producing a dynamic visual tension. These paintings exemplify Monet’s interest in travel and cultural influence, as well as his ability to adapt his techniques to new environments.

Floral subjects, though less central than landscapes and urban scenes, also played an important role in Monet’s career. His iris series, painted between 1914 and 1917, highlights his continued interest in color, form, and light. By focusing on subtle variations in hue and the delicate interplay of shapes, Monet captures the ethereal beauty of these flowers. The works are contemplative and serene, offering viewers a moment of quiet reflection. Similarly, Monet’s series of sunflowers, though often overshadowed by other artists’ interpretations, demonstrates his exploration of light’s effect on floral forms and his fascination with the vibrant possibilities of color.

Throughout his career, Monet remained committed to exploring the essence of visual perception. Whether depicting gardens, cityscapes, or flowers, he consistently focused on the interplay of light, color, and atmosphere. His repeated studies of the same subject under varying conditions reflect a scientific curiosity and an artistic sensitivity, bridging observation with expression. Monet’s ability to render ordinary scenes extraordinary through the manipulation of color and form remains a hallmark of his work, inspiring admiration from both scholars and casual observers alike.

In addition to technical mastery, Monet’s paintings resonate because of their emotional and psychological depth. His works encourage viewers to engage actively with the visual experience, noticing subtle shifts in light, movement, and reflection. By creating an immersive sense of time and place, Monet invites contemplation and connection with the natural and constructed world. His paintings are not only visual records but also explorations of perception, mood, and the fleeting beauty of existence.

Monet’s influence extends beyond the canvas. His approach to capturing ephemeral qualities of light and environment shaped Impressionism and informed subsequent modern art movements, including Post-Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism. Artists such as Renoir, Pissarro, and later American Impressionists drew on his techniques, while his exploration of color and atmosphere resonates in contemporary art practices. Monet’s work demonstrates that painting is not merely about representation but about capturing the essence of experience, a principle that continues to inspire creative expression worldwide.

By studying Monet’s masterpieces, one gains insight into the evolution of modern art. His experimentation with color, brushwork, and series painting represents a profound shift in artistic priorities, emphasizing perception, emotion, and transience. Works such as the water lilies, Houses of Parliament, Waterloo Bridge, and Impression, Sunrise, illustrate his pioneering approach and enduring appeal. Even today, these paintings captivate audiences with their beauty, technical innovation, and philosophical depth, highlighting the timeless relevance of Monet’s artistic vision.

Claude Monet’s artistic genius lies not only in the subjects he painted but in the techniques and stylistic innovations that allowed him to capture the ephemeral beauty of the world. Throughout his career, Monet continually experimented with brushwork, color, composition, and series painting, refining a unique approach that distinguished him as the pioneer of Impressionism. This part explores the core elements of Monet’s technique, his approach to recurring subjects, and the evolution of his style across decades, offering insight into what makes his paintings both timeless and transformative.

One of the defining aspects of Monet’s work is his treatment of light and color. From early in his career, he recognized that light transforms perception and alters the appearance of colors and forms. In landscapes, he often painted the same scene at different times of day or during varying weather conditions to explore these shifts. The grainstack series is a perfect example of this method. By depicting a single haystack in multiple lighting conditions—morning, noon, and evening, across summer and winter—Monet revealed how the same object could appear entirely different depending on atmospheric factors. This exploration went beyond mere observation; it was an experiment in understanding how light interacts with color and texture, and how these changes affect human perception.

Monet’s brushwork also reflects a revolutionary approach. Rather than striving for smooth, detailed surfaces, he embraced broken, visible strokes to convey movement and vitality. In paintings like “Impression, Sunrise,” loose, rapid brushstrokes create a sense of spontaneity, capturing the fleeting impression of the harbor scene rather than its exact physical details. This approach allowed Monet to convey both the sensory experience of the environment and the emotional response it provoked. The broken brushstroke technique became a hallmark of Impressionism, influencing countless artists who sought to capture the immediacy of their subjects.

Another key feature of Monet’s style is his focus on reflections and surfaces, particularly water. The water lily series, for example, demonstrates his ability to render the subtle interplay of light and reflection. In these paintings, the surface of the pond becomes both subject and medium, reflecting sky, vegetation, and floating flowers in overlapping layers. Monet often blurred the distinction between objects and their reflections, creating compositions that verge on abstraction while retaining recognizable forms. This technique emphasizes the transitory qualities of light and atmosphere, inviting viewers to contemplate the fluidity of perception.

Monet’s approach to composition was equally innovative. He often avoided traditional linear perspective, choosing instead to create a sense of depth through color modulation, overlapping forms, and subtle tonal contrasts. In “Woman with a Parasol,” for instance, the placement of figures against a backdrop of sky and grass creates a dynamic sense of space. The wind-swept dress and raised parasol guide the eye across the canvas, while the diagonal lines of the figures’ movement convey a sense of immediacy and naturalism. This compositional approach allows the viewer to feel immersed in the scene, experiencing it as Monet perceived it rather than as a static image.

Series painting was central to Monet’s artistic philosophy. By revisiting the same subject repeatedly, he could study the interaction of light, atmosphere, and color in depth. Beyond the grainstacks, series such as the Houses of Parliament, Waterloo Bridge, and the Rouen Cathedral demonstrate this dedication. In each series, subtle differences in hue, saturation, and brushwork capture distinct moments in time and variations in weather conditions. Monet’s commitment to series painting reflects both a scientific curiosity and an aesthetic goal: to document the mutable qualities of perception while creating compositions that transcend mere representation.

Monet’s mastery of color was deeply informed by his understanding of its emotional impact. He often employed complementary colors to create vibrancy and contrast, using bold yet harmonious combinations to evoke mood and sensation. For instance, in his water lilies, he balanced the soft greens and blues of foliage and water with hints of pink, violet, or white blossoms, producing a luminous, almost dreamlike quality. In urban scenes like the Houses of Parliament, subtle oranges and purples suggest sunrise or sunset, imbuing the industrial landscape with warmth and intimacy. This careful manipulation of color demonstrates Monet’s sensitivity to both the physical and emotional dimensions of his subjects.

Over the decades, Monet’s style evolved in response to personal experience, environmental conditions, and changing artistic priorities. In his early works, such as landscapes of Normandy and the port of Le Havre, he displayed a fascination with accurate observation combined with fluid brushwork. These paintings often balanced realism with the impressionistic emphasis on light and atmosphere. As his career progressed, particularly in his Giverny period, Monet moved toward more abstract, meditative compositions, emphasizing color harmonies and the interaction of forms over strict representation. The later water lily paintings, for example, verge on abstraction, with overlapping reflections and fragmented shapes that convey a sensory experience more than a physical space.

Monet’s travels also influenced his technique and subject matter. Visits to Venice, London, and other European locales introduced him to new lighting conditions, architectural forms, and environmental effects. Paintings of San Giorgio Maggiore at dusk, for instance, reflect his interest in the vibrant interplay of sunset light, water reflection, and architectural solidity. In London, the foggy atmosphere and industrial haze inspired his Houses of Parliament and Waterloo Bridge series, demonstrating his fascination with atmospheric conditions unique to urban landscapes. Through travel, Monet expanded his observational repertoire, adapting his techniques to diverse environments while maintaining his signature focus on light and perception.

The emotional resonance of Monet’s work is another significant aspect of his artistry. He sought to capture not only the appearance of the world but also its psychological and emotional impact. In the water lily series, the serene, contemplative atmosphere invites viewers to pause and reflect, offering a sense of tranquility. In urban series, the diffused light and fog evoke quiet introspection, transforming industrial landscapes into poetic experiences. Even in his depictions of family, such as “Woman with a Parasol,” Monet conveys motion, vitality, and fleeting joy, emphasizing the ephemeral nature of time and experience. This emotional depth enhances the aesthetic appeal of his work, allowing it to resonate across generations.

Monet’s use of layering and glazing techniques further contributed to the richness of his paintings. By applying multiple layers of thin paint, he could achieve depth, luminosity, and subtle color variation. In water and sky, these layers mimic the complex interactions of light, reflection, and shadow, producing a sense of atmosphere that feels both natural and heightened. This method also allowed Monet to manipulate the surface of the canvas, creating textures that enhance the sensory experience and engage the viewer on multiple levels.

In addition to technical innovation, Monet’s work demonstrates a philosophical approach to observation. He believed that nature and perception were in constant flux, and that art should capture these transient moments. His repeated studies, experiments with light, and series of paintings reflect a lifelong inquiry into the nature of seeing. Monet’s commitment to observation over representation challenged traditional artistic norms and laid the groundwork for modern approaches to visual experience, including abstract and conceptual art. His work emphasizes that the artist’s role is not merely to replicate reality but to interpret and convey the essence of perception itself.

Monet’s influence on subsequent artists and movements is profound. Impressionism, which he helped define, inspired developments in Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and abstract painting. Artists such as Renoir, Pissarro, and Cézanne drew on his emphasis on light and color, while later modernists explored the abstraction inherent in his work. Monet’s legacy also extends into contemporary art, where his explorations of color, atmosphere, and perception continue to inform experimental approaches to painting and digital visual media.

In summary, Monet’s techniques and stylistic innovations reveal the depth of his artistic vision. Through brushwork, color, composition, layering, and repeated observation, he created a visual language capable of capturing both the physical world and the ephemeral qualities of experience. His evolving style, shaped by environment, travel, and personal insight, demonstrates a lifelong dedication to exploring perception, light, and emotion. By understanding Monet’s methods and artistic evolution, one gains insight into why his paintings remain influential, timeless, and deeply engaging.

Monet’s mastery lies in the fusion of observation and interpretation. Each painting, whether a serene pond, a bustling urban bridge, or a quiet floral study, reflects a nuanced understanding of light, color, and atmosphere. His work encourages viewers to look closely, notice subtle changes, and engage with the world more attentively and reflectively. This combination of technical brilliance and perceptual sensitivity ensures that Monet’s paintings continue to captivate audiences, inspiring both aesthetic appreciation and intellectual engagement.

Claude Monet’s influence on art and culture extends far beyond his own lifetime. As the founder of Impressionism, he not only revolutionized painting techniques but also transformed the way viewers perceive the world through art. His work reflects a profound understanding of light, color, and perception, capturing the fleeting moments of nature, urban life, and intimate personal scenes in a way that continues to inspire artists, scholars, and audiences worldwide. This final part examines Monet’s legacy, the cultural and artistic impact of his work, and how his vision continues to resonate in contemporary art and society.

Monet’s artistic achievements lie in his ability to merge technical skill with perceptual insight. His paintings are more than representations of the natural or built environment; they are studies in how light, atmosphere, and color shape human perception. This approach challenged the rigid conventions of 19th-century academic art, which emphasized precise detail, historical subject matter, and idealized forms. By focusing on the ephemeral qualities of light and the sensory experience of observing the world, Monet helped redefine the role of the artist, shifting attention from replication to interpretation. This philosophical innovation paved the way for subsequent modern art movements, from Post-Impressionism to Abstract Expressionism.

The water lily series exemplifies Monet’s impact on both artistic technique and cultural perception. These paintings, created in the later years of his life at Giverny, blend naturalistic observation with a near-abstract exploration of color and reflection. The overlapping forms of lily pads, flowers, and mirrored water create a dynamic composition that engages the viewer’s senses. Each canvas is unique, capturing a specific moment in time and a particular quality of light. Beyond their aesthetic beauty, these works reflect Monet’s meditative approach to life and art. The water lilies encourage reflection—both literal and metaphorical—inviting viewers to experience serenity and contemplation. In doing so, Monet elevated landscape painting to a form of visual philosophy, emphasizing emotional and perceptual depth over strict realism.

Monet’s urban series, such as the Houses of Parliament and Waterloo Bridge, demonstrate his fascination with atmospheric conditions and industrial modernity. By painting these scenes under different weather and lighting conditions, he revealed the transformative effects of fog, mist, and sunlight on familiar structures. The Houses of Parliament, for instance, are depicted in a wide range of tones and moods, from glowing dawn to twilight haze. Similarly, the muted yet evocative renderings of Waterloo Bridge highlight the interplay between industrial landscapes and natural elements. These series reveal Monet’s ability to find beauty and poetry in everyday urban environments, challenging the notion that only natural or pastoral scenes were worthy of artistic attention.

Monet’s exploration of perception extended to his use of color. He often employed complementary colors to create vibrancy and depth, balancing warm and cool tones to convey mood and atmosphere. In works such as the Rouen Cathedral series, he demonstrated how subtle shifts in lighting could transform the perception of architectural form, creating almost sculptural effects through color alone. This approach highlights Monet’s understanding of color theory and its expressive potential. His paintings, therefore, are not merely visual depictions but sophisticated studies in the emotional and perceptual impact of color, influencing both his contemporaries and generations of artists to come.

Series painting, one of Monet’s defining methods, underscores his dedication to systematic observation and experimentation. By returning repeatedly to the same subject, he explored the nuances of light, weather, and seasonal change in extraordinary detail. Grainstacks, poplars, haystacks, and water lilies were painted multiple times under varying conditions, emphasizing the impermanence and variability of visual experience. This approach parallels scientific observation, treating the subject as a controlled study of atmospheric and perceptual conditions. Yet Monet’s work is simultaneously artistic and expressive, blending methodical study with emotional and aesthetic resonance. This duality—scientific rigor married to emotional expression—cements his place as a pioneering figure in modern art.

Monet’s personal life and environment played a significant role in shaping his artistic vision. His home and gardens at Giverny were not just a backdrop but a source of endless inspiration. He meticulously designed and cultivated the gardens, including the iconic Japanese bridge and pond, to serve as subjects for his paintings. This immersive environment allowed Monet to experiment with composition, reflection, and the effects of light across water and flora. In his later years, as eyesight began to decline, Monet’s work became increasingly abstract, focusing on color relationships and the interplay of form and reflection. Even in his final years, he continued to innovate, demonstrating a lifelong commitment to artistic growth and experimentation.

Monet’s exploration of atmospheric effects also influenced the broader cultural perception of weather and light in art. Before Impressionism, fog, mist, and diffuse lighting were often considered unworthy of detailed depiction. Monet, however, celebrated these transient phenomena, using them to convey mood and subtle shifts in perception. This approach reshaped both artistic conventions and public appreciation of the environment, encouraging viewers to see beauty in everyday atmospheric conditions. By presenting familiar scenes under changing light, Monet emphasized the dynamic and impermanent nature of the world, reflecting a modern sensibility attuned to flux, variation, and impermanence.

The cultural significance of Monet’s work extends to its role in shaping public engagement with art. Impressionist exhibitions, initially controversial, gradually garnered appreciation and respect, influencing how audiences approached visual experience. Monet’s ability to evoke emotion and sensory engagement encouraged viewers to look more attentively, fostering an appreciation for subtle nuances of light, color, and form. His work bridged the gap between professional artistic circles and the general public, making modern art accessible while maintaining intellectual and aesthetic depth. Today, Monet’s paintings are widely celebrated in museums, galleries, and private collections around the world, continuing to captivate diverse audiences with their beauty and insight.

Monet’s influence on later artists is profound and multifaceted. Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir drew inspiration from his use of color, light, and perception. Fauvist painters, including Henri Matisse, adopted his vibrant palette and expressive brushwork, while abstract and modern artists recognized the near-abstract qualities in his water lily compositions and urban series. Beyond painting, Monet’s exploration of light and perception has influenced photography, film, and digital visual arts, demonstrating the enduring relevance of his ideas in contemporary creative practice.

In addition to technical influence, Monet’s philosophical approach to art resonates in broader cultural contexts. His focus on impermanence, observation, and the interplay of perception and emotion aligns with contemporary understandings of mindfulness and attentiveness. By emphasizing fleeting moments, transient beauty, and the emotional impact of light and color, Monet’s work encourages viewers to engage deeply with the present, appreciating subtleties that might otherwise go unnoticed. This philosophical dimension elevates his paintings from decorative objects to tools for contemplation, reflection, and aesthetic education.

Monet’s legacy is also reflected in the continued study and exhibition of his work. Scholars analyze his brushwork, color theory, and compositional strategies, while curators present his series in ways that highlight the evolution of light, time, and atmosphere. Retrospective exhibitions allow audiences to experience the continuity and variation within his series, offering insight into his systematic approach to observation and expression. This ongoing engagement ensures that Monet’s contributions remain relevant to contemporary discourse in art history, visual culture, and education.

The lasting popularity of Monet’s work also underscores its emotional and aesthetic appeal. His paintings evoke serenity, wonder, and curiosity, inviting viewers to explore both the depicted scene and their own perceptual responses. The water lily series, for instance, provides a meditative experience, while urban fog and mist scenes provoke contemplation of industrial and environmental transformation. Floral studies highlight the transient beauty of natural forms, encouraging attention to detail and color. Across all subjects, Monet’s mastery of observation, technique, and expressive nuance ensures that his paintings continue to resonate with audiences of all ages and backgrounds.

Monet’s contribution to art can also be understood in terms of his challenge to traditional hierarchies of subject matter. By elevating ordinary landscapes, gardens, and urban scenes to subjects worthy of serious artistic investigation, he expanded the possibilities of painting and broadened public appreciation of visual culture. His work demonstrated that beauty and significance can be found in everyday life, and that emotional and perceptual engagement are central to artistic experience. This democratization of subject matter helped shape modern and contemporary art, encouraging artists to explore diverse environments and experiences with equal seriousness.

Claude Monet’s extraordinary career was driven not only by technique and innovation but also by an unceasing curiosity about the world around him. His work demonstrates a profound engagement with nature, urban environments, human presence, and seasonal change. While his paintings are often celebrated for their beauty, they also reveal patterns, recurring themes, and influences that shaped both the content and style of his art. This part delves into the inspirations behind Monet’s masterpieces, examines the thematic motifs that run through his work, and explores the broader impact of his artistic vision on subsequent generations.

One of Monet’s primary sources of inspiration was nature itself. From the verdant gardens of his childhood to the meticulously cultivated grounds at Giverny, Monet was surrounded by natural forms that sparked his imagination and shaped his artistic philosophy. He observed landscapes with an extraordinary sensitivity to light, color, and temporal change. The play of sunlight across a field, the reflection of the sky in water, or the subtle transformation of flowers with the seasons all became subjects of intense study. His water lily series exemplifies this engagement, transforming a simple pond into an infinite study of reflection, color, and composition. Monet’s fascination with the fluidity and impermanence of natural scenes encouraged experimentation with color harmonies and brushwork, which allowed him to convey the sensory experience of seeing, rather than just the appearance of objects.

Water itself was a recurring motif in Monet’s work, often serving as both subject and medium. Ponds, rivers, canals, and coastal scenes recur throughout his oeuvre, offering a vehicle for exploring light, reflection, and atmospheric conditions. In the Giverny pond series, the Japanese bridge provides a structural anchor for the compositions, yet the real focus remains on the surface of the water and its interplay with surrounding foliage and sky. Monet’s treatment of water surfaces—fluid, reflective, and dynamic—demonstrates his capacity to render complex optical phenomena with elegance and subtlety. The water lily paintings, in particular, blur the line between figuration and abstraction, encouraging viewers to consider not only what they see but how they perceive it.

Urban environments also featured prominently in Monet’s thematic repertoire. London, with its fog, industrial haze, and historic architecture, provided a contrasting source of inspiration to his rural landscapes. His Houses of Parliament series and the studies of Waterloo Bridge reveal a fascination with how atmospheric conditions alter familiar structures. Fog, smoke, and mist create a sense of ambiguity and mystery, emphasizing light, shadow, and tonal variation over architectural detail. These works illustrate Monet’s belief that perception is a central component of visual experience and that even industrial or urban scenes can become poetic under the right conditions.

Monet’s approach to human presence in landscapes is another defining theme. While many of his most famous works depict gardens, water, or urban scenery, he often integrated figures to enhance the sense of life and scale within a composition. “Woman with a Parasol” demonstrates his ability to capture motion and gesture in a fleeting moment. The wind-swept parasol and flowing dress not only animate the scene but also connect the human figure to its environment. Similarly, family portraits and casual outdoor scenes reflect Monet’s interest in the intersection of everyday life with natural surroundings. These compositions highlight both the physical and emotional dimensions of presence, emphasizing spontaneity, intimacy, and the temporal quality of experience.

Seasonal and temporal change is another recurring motif throughout Monet’s work. From early morning light to twilight, from summer bloom to winter frost, Monet’s paintings often explore how time and season influence perception. The grainstack series exemplifies this exploration, with the same subject depicted in different weather and lighting conditions. Each variation is unique, emphasizing subtle shifts in color, shadow, and atmosphere. This repeated observation reflects both artistic and scientific curiosity, suggesting that art is a method of understanding the world as much as a means of representation. By studying temporal and seasonal shifts, Monet demonstrated that beauty resides not only in form but also in change and impermanence.

Monet was also deeply inspired by other cultures and artistic traditions. His garden at Giverny incorporated elements of Japanese design, including the arched bridge, carefully arranged flora, and reflective water elements. These influences are visible in the composition and structure of many water lily paintings, where balance, rhythm, and asymmetry evoke Eastern aesthetics. This integration of foreign design principles illustrates Monet’s openness to cross-cultural inspiration and his ability to adapt such influences seamlessly into his own artistic vocabulary. Additionally, his travels to Venice expanded his visual repertoire, inspiring new color palettes, light effects, and compositional techniques, as seen in the luminous depictions of San Giorgio Maggiore.

Monet’s fascination with series painting is not merely technical but also thematic. By painting the same subject multiple times under varying conditions, he highlighted the interconnectedness of perception, time, and environment. The Rouen Cathedral series, for example, examines the subtle shifts in light and shadow across the cathedral’s façade. Each painting emphasizes different atmospheric qualities, capturing the way sunlight, mist, and shadow alter visual experience. Through this approach, Monet transformed repetitive observation into an artistic philosophy, emphasizing that understanding comes through careful, sustained engagement with the world.

Light and color are central to Monet’s thematic exploration. He understood that light does more than illuminate—it defines space, mood, and perception. By manipulating color intensity, hue, and contrast, he could evoke a wide range of sensations, from the tranquil calm of a lily pond to the dramatic vibrancy of a sunrise over water. The juxtaposition of warm and cool tones, as well as the interplay of complementary colors, creates visual harmony and evokes emotional resonance. In essence, Monet’s use of light and color transcends literal representation, functioning as a language through which he communicates perception, sensation, and emotion.

Monet’s attention to atmospheric and perceptual phenomena also connects to broader cultural and philosophical currents of his time. Impressionism, as a movement, emphasized the importance of immediate visual experience, and Monet’s work epitomized this focus. By capturing transient effects of light, weather, and movement, he challenged traditional artistic hierarchies and invited viewers to reconsider the significance of ordinary moments. This democratization of subject matter and attention to sensory experience aligned with contemporary shifts in society, including urbanization, scientific inquiry, and changing notions of beauty and value. Monet’s paintings thus function as both aesthetic objects and cultural documents, reflecting a modern sensibility attuned to observation, variability, and impermanence.

Another important thematic pattern in Monet’s work is the blurring of boundaries between realism and abstraction. Particularly in his later years, his water lily paintings and large-scale landscapes verge on abstraction, with forms overlapping and dissolving into color and reflection. These compositions challenge conventional expectations of perspective, structure, and narrative, inviting viewers to engage with the paintings in a more interpretive, experiential way. By approaching abstraction through observation rather than invention, Monet bridged the gap between naturalism and modern abstraction, influencing movements such as Abstract Expressionism and informing contemporary approaches to color and composition.

Monet’s influence extends beyond painting into wider cultural consciousness. His depiction of gardens, rivers, urban streets, and architectural forms has shaped public perceptions of natural and built environments, encouraging audiences to appreciate the interplay of light, color, and atmosphere in everyday life. His paintings have inspired literature, photography, design, and even modern digital visual arts, demonstrating that the principles of Impressionism—observation, sensory engagement, and attention to transience—have broad applicability across creative disciplines. Monet’s vision of seeing, capturing, and interpreting the world continues to inform contemporary artistic practices and educational approaches in art appreciation.

The emotional resonance of Monet’s paintings is another aspect of his enduring influence. His works encourage contemplation, evoke serenity, and invite introspection. Whether observing the mirrored surface of a pond, the haze over a London bridge, or the delicate petals of an iris, viewers are drawn into a sensory experience that transcends time and place. Monet’s paintings act as portals, allowing audiences to experience light, color, and atmosphere as he did, fostering a deeper appreciation of perceptual subtlety and aesthetic nuance. This emotional engagement ensures that his art remains relevant, inspiring, and accessible to diverse audiences around the world.

Monet’s role in shaping the Impressionist movement also amplifies his cultural significance. By challenging conventions, advocating for new artistic methods, and consistently producing work that explored perception and light, he helped establish Impressionism as a major force in modern art. The movement influenced generations of artists, from contemporaries such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Camille Pissarro to later innovators in Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and abstraction. Monet’s emphasis on series painting, atmospheric study, and the expressive potential of color continues to inform artistic practices today, underscoring the longevity of his contributions.

In addition to technical and philosophical impact, Monet’s work has had a broad influence on art collections, museum curation, and the public’s understanding of modern art. His paintings are prominently displayed in major institutions worldwide, forming central components of exhibitions on Impressionism and modern visual culture. Retrospectives allow viewers to witness the evolution of his technique, the thematic continuity of his series, and the subtle variations in light and color that define his artistic approach. Through these exhibitions, Monet’s work educates, inspires, and fosters a continuing dialogue between the viewer and the painting.

Monet’s legacy also underscores the importance of patience, observation, and repeated study in artistic creation. His repeated engagement with subjects, attention to transient conditions, and meticulous layering of color illustrate a disciplined approach to creativity. These practices have influenced both professional artists and amateurs, highlighting the value of sustained engagement and observation in developing visual literacy and expressive skill. By modeling a method that balances experimentation, discipline, and emotional resonance, Monet’s career provides a framework for understanding how art can capture the interplay between perception and experience.

Finally, Monet’s enduring popularity speaks to the universal appeal of his vision. The themes he explored—nature, light, perception, impermanence, and beauty—resonate across cultures and generations. His work reminds viewers of the power of observation, the richness of ordinary life, and the profound impact of subtle shifts in light, color, and atmosphere. Monet’s paintings are not only artistic achievements but also tools for reflection, inspiring both aesthetic appreciation and mindfulness. By engaging with his work, audiences encounter a world in which beauty is everywhere, waiting to be noticed, appreciated, and interpreted.

Claude Monet’s later years represent the culmination of a lifetime devoted to observation, light, and the emotional resonance of color. As he aged, Monet’s artistic vision became increasingly introspective, meditative, and experimental. Despite facing personal challenges, including declining eyesight and health issues, he continued to produce some of his most innovative and iconic works, leaving a legacy that would influence not only his contemporaries but also generations of modern and contemporary artists. This part explores Monet’s late period, examining his final masterpieces, evolving techniques, and the enduring relevance of his artistic philosophy.

Monet’s later works are characterized by a heightened focus on abstraction, atmosphere, and the interplay of light and color. In his iconic water lily series, created during his final decades at Giverny, he moved beyond strict representation to explore how forms, reflections, and color harmonies could convey mood and perception. These canvases often lack a traditional horizon line or defined structure, allowing viewers to become immersed in the fluid, shimmering surface of water and the delicate forms of lilies. The result is a body of work that borders on abstraction while remaining grounded in observation, demonstrating Monet’s ability to balance realism with expressive innovation.

During this period, Monet’s eyesight began to deteriorate due to cataracts, which altered his perception of color and light. Interestingly, this condition influenced his artistic approach, encouraging him to experiment further with bold colors, diffuse forms, and expressive brushwork. Paintings from this era show a remarkable sensitivity to color contrasts and the effects of light, creating a luminous, almost dreamlike quality. Monet’s determination to continue painting despite physical challenges underscores his commitment to artistic exploration and demonstrates how adversity can inspire new creative directions.

The late water lily paintings exemplify Monet’s evolving mastery of composition. These monumental works often feature large canvases filled edge-to-edge with overlapping reflections, leaves, and blossoms. By eliminating the horizon and background distractions, Monet directed the viewer’s attention entirely to the surface of the pond, where color, light, and texture interact in complex, dynamic patterns. The result is an immersive visual experience that invites contemplation and emotional engagement. These paintings highlight Monet’s belief that the essence of a scene lies not in its literal form but in the perception of its atmosphere, light, and mood.

Monet’s gardens at Giverny continued to serve as a primary source of inspiration during his final years. He meticulously cultivated the Japanese bridge, water lilies, and surrounding flora, treating the garden itself as a living studio. The changing seasons, subtle variations in weather, and reflections on the water provided endless opportunities for observation and experimentation. This immersive environment allowed Monet to refine his techniques and deepen his exploration of color, light, and perception. His dedication to the garden as both subject and artistic laboratory underscores the integration of life and art in his creative philosophy.

Series painting remained a central element of Monet’s late work. Beyond the water lilies, he continued to revisit subjects like the Rouen Cathedral and London’s Waterloo Bridge, experimenting with atmospheric conditions, lighting variations, and compositional perspectives. Each painting captures a specific moment in time, revealing how light and weather transform familiar forms. In doing so, Monet emphasized the impermanence and dynamism of the visual world, reinforcing a key tenet of Impressionism: that beauty exists in transient, fleeting moments.

Monet’s late style also demonstrates an increasing preoccupation with texture and surface. Through thick, layered brushstrokes and impasto techniques, he created canvases that are tactile as well as visual experiences. The layering of color and subtle modulation of tone produces depth, movement, and luminosity, inviting viewers to engage with the paintings on multiple sensory levels. This textural richness enhances the emotional impact of his works, transforming ordinary subjects into profound meditative experiences.

In addition to technical and stylistic innovations, Monet’s later works reflect a philosophical dimension. By focusing on perception, atmosphere, and the transient qualities of light, he explored fundamental questions about how humans experience the world. His paintings invite viewers to consider not only what they see but also how they perceive it. This approach aligns with broader intellectual currents of the time, including an increased interest in psychology, perception, and the science of vision. Monet’s art, therefore, transcends aesthetic pleasure, offering insight into human consciousness and the nature of observation.

Monet’s influence in his final years extended beyond his own studio. By the time of his death in 1926, Impressionism had firmly established itself as a dominant movement in modern art, and Monet was widely recognized as one of its most influential figures. His emphasis on light, color, and perception had inspired contemporaries such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, while Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh adopted and expanded upon his innovative use of color and brushwork. Monet’s late works, with their abstract qualities and expressive freedom, also presaged developments in modernism, including abstraction and Color Field painting.

The cultural and historical significance of Monet’s late works is evident in their continued prominence in museums, galleries, and exhibitions worldwide. Paintings such as “Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge” and “The Grand Canal, Venice” are celebrated not only for their beauty but also for their demonstration of advanced artistic technique and perceptual insight. They remain central to discussions of Impressionism, modernism, and the evolution of Western art. Through these works, Monet’s late career provides a lens through which audiences can explore both the progression of his own artistic practice and the broader trajectory of art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Monet’s legacy also encompasses his contributions to public appreciation of art and the environment. By emphasizing natural light, atmospheric conditions, and the beauty of everyday scenes, he encouraged viewers to engage more attentively with their surroundings. His paintings foster an appreciation for fleeting moments, subtle visual changes, and the sensory qualities of the world. In this sense, Monet’s art serves as a bridge between the external environment and internal perception, inviting contemplation and mindfulness. His work reminds us that observation itself can be an aesthetic and reflective practice.

Furthermore, Monet’s integration of personal experience into his art demonstrates the intimate connection between life and creativity. His family, his gardens, and his immediate surroundings were not merely subjects but extensions of his artistic vision. This integration of lived experience and artistic production highlights the role of personal engagement in generating profound and meaningful work. Monet’s late paintings, therefore, are not only visual masterpieces but also reflections of a life devoted to observing, interpreting, and celebrating the world.

Monet’s final years were marked by a remarkable combination of perseverance and innovation. Despite physical limitations, he continued to experiment, refine his style, and produce works of lasting significance. His ability to evolve artistically while remaining true to his core vision illustrates the enduring relevance of dedication, curiosity, and creative exploration. Monet’s late paintings encapsulate his artistic philosophy: that the world is a dynamic, ever-changing interplay of light, color, and perception, and that art should strive to capture these ephemeral qualities.

The global influence of Monet’s late works extends beyond traditional painting. His exploration of light and reflection has inspired photography, cinematography, and digital art, demonstrating the cross-disciplinary impact of his vision. Contemporary artists continue to draw on his approach to color, atmosphere, and abstraction, highlighting the ongoing relevance of his innovations. In education, Monet’s work serves as a key example for teaching color theory, composition, and the study of perception, ensuring that his methods continue to inform and inspire future generations of artists and art enthusiasts.

In conclusion, Claude Monet’s late years represent a period of artistic maturity, experimentation, and profound influence. His final works, particularly the water lily series, embody the synthesis of observation, emotion, and innovation that defines his legacy. By exploring light, color, atmosphere, and the ephemeral qualities of perception, Monet expanded the possibilities of painting and transformed the way viewers engage with the visual world. His perseverance, creativity, and philosophical approach to art ensure that his influence continues to resonate across cultures, artistic disciplines, and generations.

Monet’s enduring legacy lies not only in his technical brilliance but also in his capacity to inspire deeper awareness of the world around us. His late works invite contemplation, evoke emotion, and encourage perceptual engagement, reminding us that art is a dialogue between observation and interpretation. Through his paintings, Claude Monet continues to offer a vision of beauty, impermanence, and sensory wonder, securing his place as one of the most influential and celebrated artists in history.

Final Thoughts:

Claude Monet’s legacy is a testament to the transformative power of observation, color, and light. Across his lifetime, he redefined what painting could capture, shifting the focus from mere representation to the experience of seeing. From serene water lilies to misty London bridges, from vibrant floral studies to intimate family moments, his work demonstrates a profound sensitivity to the ephemeral and a remarkable ability to convey mood, atmosphere, and emotion through visual means.

Monet’s dedication to repeated observation, experimentation with light, and mastery of color allowed him to elevate ordinary subjects into extraordinary experiences. His series of paintings, such as the grainstacks, Rouen Cathedral, and Waterloo Bridge, reveal how subtle variations in lighting and perspective can transform the same scene into countless unique compositions. This emphasis on temporality and perception has influenced generations of artists and continues to inspire modern approaches to painting, photography, and visual storytelling.

Beyond his technical innovations, Monet’s art resonates because of its universal appeal. His paintings invite viewers to pause, reflect, and engage with the world more attentively. They encourage appreciation for the beauty of everyday life and the transient qualities of nature, fostering a deeper connection to our environment and our own perceptions. Monet’s work reminds us that art is not only about what we see but also about how we experience it.

In celebrating Claude Monet, we recognize a pioneer whose vision expanded the boundaries of art. He transformed landscapes, urban scenes, and intimate moments into timeless studies of light, color, and perception. His influence remains pervasive in contemporary art and culture, and his masterpieces continue to captivate audiences worldwide. Monet’s paintings are more than visual delights—they are invitations to experience the world with wonder, attentiveness, and imagination.

Ultimately, Claude Monet’s genius lies in his ability to make the fleeting permanent, to turn light and atmosphere into lasting expressions of beauty. His work endures because it speaks to the human desire to see, to feel, and to connect with the world in a profound and meaningful way. As long as people continue to look at his paintings, Monet’s vision will remain alive—ethereal, inspiring, and timeless.