Focus is one of the most crucial aspects of photography. Without a well-chosen focus point, even the most visually striking images can fail to capture attention. A photograph’s sharp area tells the viewer where to look and guides them through the story you are trying to convey. Mastering focus requires understanding how your camera works and how different subjects and styles of photography demand unique approaches. For a beginner photographer, the concept of focus can seem overwhelming, especially with so many modes, lenses, and techniques available. However, taking the time to understand focus and how to direct it in a photograph can drastically improve the quality of your images. Focus is not only about achieving technical sharpness; it is about controlling the visual journey of the viewer’s eye. It determines which elements are emphasized, which are secondary, and how the overall composition communicates a narrative or mood.

At its core, focus is about ensuring that the part of the image you want to emphasize is sharp and clear, while other elements may fall into softer blur depending on your artistic intention. Cameras achieve focus either mechanically or electronically, and the way you control this process can significantly impact your photography. Most modern cameras offer two primary focus methods: autofocus and manual focus. Autofocus has become incredibly advanced, with cameras now featuring multiple AF points that track subjects in motion or adapt to changing light conditions. For beginners, understanding autofocus modes—such as single-point AF, dynamic AF, or continuous AF—can be transformative. Single-point AF is ideal for still subjects, allowing you to precisely control exactly which part of the frame is sharp. Dynamic AF is useful when your subject moves unpredictably; the camera selects surrounding points to maintain focus if the initial point loses the subject. Continuous AF, often called AI Servo on Canon or AF-C on Nikon and Sony, is essential for tracking moving subjects like athletes, children, or animals. Manual focus, by contrast, gives the photographer full control over sharpness and is often used in macro, landscape, or low-light photography where autofocus may struggle. Understanding when to switch from autofocus to manual focus—and having the skill to execute it confidently—is a mark of a growing photographer. With manual focus, you learn to read the scene through the viewfinder or live view, adjusting the lens until your intended subject is crisp and prominent.

Focus in photography is intrinsically linked to the concept of depth of field. Depth of field refers to the area of your image that appears acceptably sharp and is influenced primarily by aperture, focal length, and distance to your subject. A wider aperture, such as f/1.8, creates a shallow depth of field, isolating your subject by rendering the background and foreground softly blurred. This technique is widely used in portrait photography to ensure the person’s eyes or face remain the viewer’s focal point. Conversely, a narrower aperture, like f/16, produces a deeper depth of field, making most of the scene appear sharp and detailed. This approach is common in landscape photography, where the goal is often to maintain clarity from foreground to background. Understanding how aperture affects focus and depth of field is essential because it allows you to control not only what is sharp but also how the viewer interprets the image.

Focus is not just technical—it is also a powerful compositional tool. A photograph’s sharp areas guide the viewer’s eye and emphasize narrative elements. For instance, in a street photography scene, focusing on a single person in a bustling crowd can immediately convey a story of isolation or movement. In nature photography, focusing on the intricate detail of a flower or insect draws attention to the beauty of small, often overlooked elements. Selective focus can also create a sense of depth and dimension in a photograph. By having a sharply focused subject against a softly blurred background, the image gains a three-dimensional quality that draws viewers into the scene. Techniques like bokeh, where the out-of-focus areas become aesthetically pleasing shapes and patterns, rely on both lens characteristics and focus control. Mastering focus thus means understanding how to balance the subject, background, and surrounding elements to create a coherent and engaging visual story.

Different genres of photography require unique approaches to focus. In portrait photography, the eyes are usually the most critical point of focus. Even a slight misalignment can make a portrait feel disconnected or unprofessional. Many photographers recommend focusing on the nearest eye to the camera to maintain a natural and engaging look. In sports or wildlife photography, focus must be fast, accurate, and adaptive. Continuous autofocus and predictive tracking become invaluable as the subject moves unpredictably. In contrast, macro photography demands painstaking precision. When capturing tiny subjects, even a millimeter shift in focus can blur essential details. Photographers often use manual focus combined with focus stacking, a technique that merges multiple images focused at different points to achieve maximum sharpness across the subject. In landscape photography, depth of field is paramount. Photographers frequently use narrow apertures and hyperfocal distance calculations to ensure both near and far elements remain sharp. Hyperfocal focusing, though technical, allows for maximum clarity throughout a scene and is a staple technique for landscape professionals.

Several factors can make achieving perfect focus challenging. Low light, fast-moving subjects, and complex scenes with multiple elements all require careful attention. For example, in dim conditions, autofocus sensors may struggle to lock onto a subject, leading to unintended blur. Similarly, photographing reflective surfaces, through glass, or in foggy environments can confuse autofocus systems. Learning how to compensate through manual focus, using focus-assist features, or adjusting camera settings is essential for overcoming these obstacles. Camera shake is another factor that can reduce perceived focus, especially at slower shutter speeds or with telephoto lenses. Tripods, image stabilization, and proper handholding techniques all play a role in maintaining sharpness. Photographers must also consider lens quality, as some lenses produce sharper images than others, especially at wide apertures. Understanding the limitations and strengths of your gear is part of mastering focus.

Beyond technical knowledge, focus in photography is also about developing your eye. Learning to see the subject that needs emphasis, anticipating movement, and understanding visual hierarchy all contribute to effective focus. Practice is critical. Spend time photographing static subjects, then gradually introduce motion, varying light, and complex scenes. Experiment with different focus points, depths of field, and compositions to see how focus changes the perception of your images. Reviewing your work critically is equally important. Analyze where the eye is naturally drawn in your photos and how focus influences that journey. Over time, you will develop intuition, allowing you to make faster, more confident decisions about where to place focus in a scene.

Finally, focus can be used creatively to convey mood, emotion, and atmosphere. Soft focus can evoke nostalgia or dreaminess, while sharp, crisp focus can create tension, immediacy, or clarity. Photographers often combine multiple focus techniques, like selective focus with motion blur or bokeh, to add depth and complexity to images. By treating focus as both a technical and artistic element, you gain the ability to tell richer visual stories. Mastering focus is a journey that blends technical understanding, creative insight, and practical experience. It is more than just ensuring the subject is sharp—it is about guiding the viewer’s eye, emphasizing what matters, and shaping the narrative of your image. Whether you are capturing intimate portraits, dynamic action, or sweeping landscapes, focus determines the clarity and impact of your photography.

By understanding your camera’s focus modes, experimenting with depth of field, and consciously deciding where to direct attention, you can elevate your photography from mere documentation to evocative storytelling. Focus, in essence, is the silent narrator of every photograph, subtly directing attention, evoking emotion, and enhancing the power of the visual medium. With time, patience, and practice, every photographer can learn to control focus not just as a technical tool, but as a vital component of their creative expression.

The Role of Focus in Storytelling

Every photograph tells a story, whether it’s the serenity of a landscape, the intensity of a wildlife encounter, the intimacy of a portrait, or the precision of a product shot. Focus is the tool that directs attention to the most important part of that story. When a subject is in sharp focus, the viewer’s eye is naturally drawn to it. The surrounding areas may be blurred or less detailed, creating a visual hierarchy that guides perception.

This principle is critical across all genres of photography. For example, in landscape photography, placing the focus correctly ensures that viewers appreciate the depth and scale of the scene. In portrait photography, focusing on the eyes of the subject conveys emotion and personality. In wildlife photography, capturing the moment with precise focus allows the viewer to feel the action and movement of the subject. Understanding how to control focus transforms photographs from mere images into compelling visual narratives.

How Focus Affects Perception

The way focus is used in a photo directly impacts how the viewer perceives the scene. Sharpness can emphasize importance, draw attention to details, or create a sense of realism. Conversely, areas intentionally left out of focus can simplify the image, remove distractions, and enhance composition. Depth of field, which is the range of distance in a photo that appears acceptably sharp, works hand in hand with focus. A wide depth of field ensures that much of the image is sharp, which is common in landscapes. Narrow depth of field isolates the subject from its surroundings, a technique frequently used in portraits and macro photography.

Focus also plays a psychological role. Humans instinctively look at the sharpest part of an image first. This means the placement of the focus point determines the sequence in which the viewer’s eye moves through the photograph. When you master this skill, you gain control over the visual storytelling process. The focus point becomes a tool for directing attention, emphasizing key elements, and conveying mood or emotion.

Understanding Camera Focus Modes

Before deciding where to focus, it is important to understand the different focus modes available on modern digital cameras. These modes allow photographers to adapt to the subject and shooting conditions. Single-point autofocus is ideal for stationary subjects, providing precise control over the focus area. Continuous autofocus is designed for moving subjects, tracking motion to maintain sharpness. Subject tracking modes combine these capabilities, following the subject automatically across the frame.

Manual focus remains a valuable tool, especially in situations where autofocus may struggle. Landscapes, macro shots, and product photography often benefit from manual adjustments. Cameras often include features like focus peaking or magnification to assist in achieving precise focus. Knowing when and how to use each focus mode gives photographers flexibility and increases the likelihood of capturing sharp, engaging images.

Choosing the Right Focus Point

Deciding where to place your focus point is influenced by the subject, composition, and the story you want to tell. In portraits, focusing on the eyes establishes a connection between the viewer and the subject. In landscapes, focusing on the midground often provides a balance between foreground and background sharpness. Wildlife photography requires anticipating movement, placing focus on the most important part of the animal, such as the eye or head, while still accounting for unpredictable motion. Product photography demands precision, with focus placed on the most critical part of the product to ensure clarity and visual impact.

The placement of the focus point also interacts with the aperture you choose. Smaller apertures increase depth of field, making more of the scene appear sharp. Larger apertures reduce depth of field, isolating the subject and creating background blur. Understanding how focus point placement and aperture work together allows photographers to control how the viewer experiences the image.

Focusing on Different Photography Genres

Different genres require different approaches to focus. Landscape photography often uses manual focus and a smaller aperture to ensure wide sharpness, with focus placed around a third into the scene. Wildlife photography requires fast autofocus and tracking modes to follow erratic movements, focusing on key features of the animal. Portrait photography usually emphasizes the nearest eye of the subject, while still life and product photography allow for careful control and adjustment of focus to highlight the most important elements. Each genre presents unique challenges and opportunities to use focus creatively.

By practicing and experimenting with these principles, photographers can develop an intuitive sense of where to focus. Over time, choosing the right focus point becomes second nature, and the resulting images will consistently engage and direct the viewer’s attention effectively.

Focusing on Landscape Photography

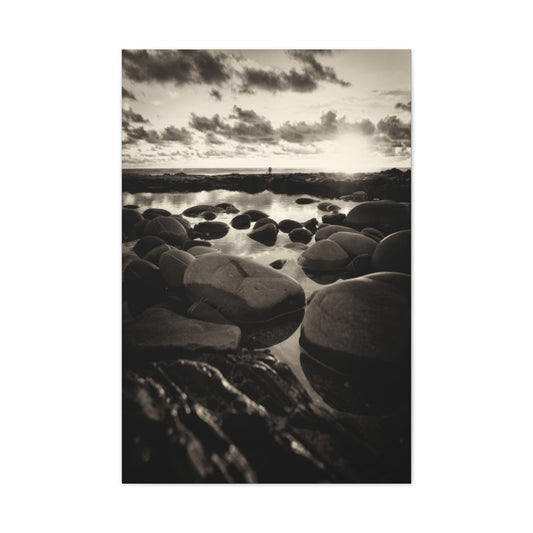

Landscape photography offers a unique challenge when it comes to focus. Unlike portrait or wildlife photography, landscapes often involve multiple planes of interest. The goal is to capture the beauty of the scene while maintaining a sense of depth and clarity. Achieving sharpness throughout the image depends not only on where you place the focus point but also on your choice of aperture, lens, and focusing technique.

Manual focus is frequently preferred in landscape photography because it allows precise control. Autofocus can sometimes struggle with vast, detailed scenes or areas of low contrast, which are common in natural landscapes. Using manual focus along with focus peaking or magnification ensures that critical areas remain sharp.

When determining the focus point in a landscape, consider whether your image has a primary subject. A lone tree, mountain peak, or building can serve as the main focal point. If the scene is more about the overall composition, such as rolling hills or a panoramic view, placing the focus approximately one-third into the frame is a reliable strategy. This midground focus helps achieve a balance, allowing both the foreground and background to appear acceptably sharp.

Aperture and Depth of Field in Landscapes

Aperture plays a central role in how focus is perceived in landscape photography. Most landscape photographers use smaller apertures, such as f/8 to f/16, to maximize depth of field. This ensures that both near and distant elements appear sharp, creating an immersive and detailed image. Smaller apertures reduce the size of the lens opening, allowing more of the scene to fall within the focus range.

However, smaller apertures also require longer exposure times. Tripods are often essential to avoid camera shake, especially in low-light conditions such as dawn or dusk. Additionally, image stabilization features in lenses or cameras may help, but they cannot fully replace a stable tripod for long exposures.

Choosing a larger aperture, like f/2.8 or f/4, can be appropriate if you want to isolate a specific subject within the landscape. This technique works well when there is a clear focal point, such as a flower in a meadow or a rock formation in the foreground. Using a wide aperture allows the background and foreground to blur, drawing attention to the subject while creating a sense of depth.

Techniques for Achieving Sharp Landscapes

Achieving sharp landscapes requires attention to several technical aspects. First, focus stacking is a valuable technique. By taking multiple shots focused at different distances and merging them in post-processing, photographers can create an image with near-perfect sharpness throughout. This method is particularly useful in macro landscapes or scenes with close foreground elements.

Second, hyperfocal distance is a practical tool for determining focus in wide scenes. Focusing on the hyperfocal distance ensures that the maximum amount of the scene appears in focus, from foreground to background. Calculators and charts can assist photographers in determining the correct hyperfocal distance based on focal length and aperture.

Tripod stability, careful composition, and checking focus through live view or magnification features are additional strategies that enhance sharpness. Taking the time to adjust focus precisely, rather than relying solely on autofocus, leads to cleaner, more professional-looking landscape images.

Focusing on Wildlife Photography

Wildlife photography presents an entirely different set of challenges compared to landscapes. Animals are unpredictable, fast-moving, and often difficult to approach. Capturing a sharp wildlife image requires a combination of camera technique, anticipation, and understanding animal behavior.

Autofocus plays a crucial role in wildlife photography. Modern cameras often include continuous autofocus or subject tracking modes, which automatically follow a moving subject while the shutter button is half-pressed. These modes ensure that the subject remains sharp even as it moves within the frame. For cameras without dedicated tracking, continuous autofocus (C-AF) can still provide reliable results.

Placing the focus point correctly is essential. For distant subjects, aim for the largest part of the animal’s body, such as the torso. When closer, focus on the eyes or head, which are the most visually engaging areas. Keeping the eyes in focus allows viewers to connect emotionally with the subject, creating a more compelling image.

Using Burst Mode and Shutter Speed

Because wildlife often moves unpredictably, using a burst or continuous shooting mode increases the likelihood of capturing a sharp image. Taking multiple shots in rapid succession allows you to select the best one, even if others are slightly blurred due to motion.

Shutter speed is another critical consideration. A fast shutter ensures that motion is frozen, avoiding blur caused by rapid movement. The necessary shutter speed depends on the subject’s speed and the focal length of the lens. For example, a bird in flight requires a faster shutter than a slowly grazing deer. Combining a fast shutter with continuous autofocus and burst mode is a standard approach for professional wildlife photographers.

Anticipating Wildlife Behavior

Understanding animal behavior can significantly improve your focus strategy. Anticipating where the subject is likely to move allows you to pre-focus or adjust camera settings in advance. Observing patterns, such as flight paths, feeding habits, or territorial behavior, provides an advantage, reducing the reliance on reactive adjustments.

In addition to focus, composition plays a role in wildlife photography. Positioning the animal within the frame, leaving space in the direction it is moving, and considering the background all enhance the visual impact. A sharp subject against a clean, non-distracting background ensures that the focus point remains effective and engaging.

Balancing Focus and Composition

Both landscape and wildlife photography benefit from a thoughtful balance between focus and composition. In landscapes, the sharpness of the main subject should complement the overall scene, guiding the viewer’s eye naturally. In wildlife, focus on key features should integrate seamlessly with the composition, emphasizing the subject while maintaining context.

Using rules of composition, such as the rule of thirds, leading lines, or framing elements, enhances the effectiveness of the focus point. The viewer’s attention is drawn first to the sharpest part of the image, and then guided through the rest of the scene. Mastery of both focus and composition ensures that images are visually appealing, technically strong, and emotionally engaging.

Challenges in Different Conditions

Both landscape and wildlife photography come with environmental challenges that affect focus. Low light, haze, fog, and fast movement can make achieving sharp focus difficult. Understanding your camera’s limitations and adjusting settings accordingly is essential. Manual focus may be necessary in low-contrast landscapes, while wildlife photographers may need to increase ISO or use faster lenses to maintain adequate shutter speeds.

Environmental awareness also includes anticipating wind, which can move foreground elements in a landscape, or understanding the terrain, which affects positioning for wildlife shots. Patience, preparation, and adaptability are key qualities for photographers aiming for consistent sharpness under varying conditions.

Post-Processing and Focus Adjustment

Post-processing tools offer opportunities to refine focus and sharpness. Software can enhance details, adjust clarity, and correct minor focus issues. Focus stacking, sharpening filters, and selective adjustments allow photographers to achieve the desired level of detail while maintaining a natural appearance. However, relying solely on post-processing is not a substitute for proper focus during shooting. Capturing the sharpest image possible in-camera remains the foundation of quality photography.

Focusing on Portrait Photography

Portrait photography is one of the most intimate forms of photography, and focus plays a central role in connecting the viewer with the subject. Unlike landscapes or wildlife, the primary goal is often to convey emotion, personality, or mood. The focus point becomes a bridge between the photographer and the viewer, directing attention to the most expressive and engaging parts of the subject.

In portrait photography, the eyes are universally recognized as the most critical area to keep in sharp focus. Humans instinctively look at the eyes first when viewing a face, making them the natural focal point. Regardless of the aperture or composition, prioritizing the eyes ensures that the portrait feels alive and engaging.

For stationary subjects, single-point autofocus or manual focus is typically ideal. By placing the focus point on the nearest eye to the camera, the photographer guarantees clarity and emotional connection. Recomposition can then be applied to achieve the desired framing without losing sharpness on the critical area.

Dealing with Moving Subjects in Portraits

Action portraits, candid shots, or photographing children introduce challenges similar to wildlife photography. Subjects may move unpredictably, requiring continuous autofocus or subject tracking to maintain sharpness. A wide focus area or zone autofocus can help capture movement while ensuring that the eyes remain clear.

Shutter speed becomes particularly important in moving portraits. A fast enough shutter freezes subtle gestures and expressions, preventing motion blur from reducing the impact of the photograph. Using burst mode to capture a series of frames increases the likelihood of obtaining a perfect moment, especially when dealing with fleeting expressions or actions.

Portrait photographers must also consider depth of field carefully. Wide apertures such as f/1.8 or f/2.8 allow the subject to stand out from the background, creating separation and emphasizing facial features. Smaller apertures, such as f/8, can keep more of the subject in focus, which is useful for group portraits or when environmental context is important.

Group Portraits and Wider Focus

When photographing groups, focusing on a single individual may not suffice. Center-weighted or zone autofocus modes help maintain overall sharpness across multiple subjects. Placing the focus in the middle of the group ensures that most faces remain acceptably sharp, especially when using moderate apertures.

Composition and spacing play an additional role in group portraits. Ensuring subjects are not spread too far apart and maintaining even distances from the camera allows the depth of field to cover everyone effectively. This approach combines technical focus decisions with creative framing to produce cohesive and clear group images.

Using Manual Focus in Controlled Environments

In controlled studio environments, manual focus can be advantageous. Photographers have the opportunity to set up lighting, pose subjects, and carefully choose the focal plane. This precision eliminates reliance on autofocus, which may sometimes struggle with reflective surfaces or low-contrast areas in studio lighting.

Focus peaking and live view magnification assist photographers in verifying that critical areas, such as the eyes, lips, or hands, are sharp. This attention to detail ensures that the final portrait communicates the intended emotion and aesthetic.

Creative Focus Techniques in Portraits

While standard portrait photography emphasizes sharp eyes, creative approaches sometimes shift the focus for artistic purposes. Shallow depth of field, selective focus, or intentional focus on secondary elements can produce unique visual effects. For instance, focusing on hands, jewelry, or a distinctive feature while letting the face blur can create a stylized image that conveys mood rather than literal representation.

Understanding when to deviate from conventional focus rules allows photographers to experiment and develop a personal style. However, knowing the standard principles first ensures that creative choices are deliberate rather than accidental.

Focusing on Still Life and Product Photography

Still life and product photography share a critical similarity with landscape photography: the photographer has complete control over the scene. This allows careful attention to focus, lighting, and composition without the unpredictability of moving subjects. Because the subject is static, achieving precise focus is both possible and essential.

Product photography often involves a single main subject, such as a piece of jewelry, a bottle, or a gadget. The focus should be placed on the most important feature of the item, ensuring that the viewer immediately notices it. Manual focus is particularly effective, as it allows incremental adjustments and precise placement of the focal plane.

Grouped Objects and Focus Distribution

In scenes with multiple items, such as food photography, lifestyle product setups, or artistic arrangements, distributing focus across key elements requires careful consideration. Center-weighted or zone autofocus modes can cover multiple items while keeping the primary subjects sharp. Aperture selection becomes vital: moderate apertures such as f/5.6 or f/8 often provide enough depth of field to include several objects while retaining separation from the background.

Maintaining cohesion in composition ensures that the viewer’s attention flows naturally from one item to another. Objects placed too far apart or at different distances from the camera may require focus stacking, a technique where multiple images are captured at different focal planes and combined in post-processing to produce a fully sharp image.

Aperture and Lens Choice in Still Life

A smaller aperture ensures that multiple objects remain sharp, while larger apertures isolate a single product from its environment. Lens choice also affects focus and depth perception. Macro lenses are ideal for close-up product shots, allowing photographers to capture fine details with precision. Standard or telephoto lenses may be used for broader setups or lifestyle contexts, where perspective and background play a more significant role.

Using manual focus with magnification tools ensures that intricate details, such as textures, labels, or patterns, are clearly defined. This is particularly important for commercial photography, where product clarity can directly impact consumer perception.

Lighting and Its Influence on Focus

Lighting affects not only the mood of still life and product photography but also how focus is perceived. Soft, diffused light minimizes harsh shadows and ensures even sharpness, while directional lighting can enhance textures and create depth. Balancing lighting with focus decisions helps guide the viewer’s eye and highlights the most important elements of the composition.

Reflective surfaces, such as glass, metal, or water, can complicate focus. Adjusting angles, using polarizing filters, or modifying light sources helps maintain sharpness without introducing glare or distraction. Attention to these details enhances both technical and visual quality.

Focus Techniques for Creative Product Photography

Creative use of focus in product photography can make images more visually engaging. A shallow depth of field can isolate the subject from a busy environment, while selective focus can highlight particular textures or features. Combining focus techniques with composition, color, and lighting produces images that are not only technically sharp but also aesthetically compelling.

Focus stacking is particularly useful for macro product photography, where extreme close-ups may otherwise result in limited depth of field. By carefully combining multiple images with different focal points, photographers can achieve fully sharp, detailed shots that maintain clarity across the entire subject.

Advanced Focus Techniques in Photography

Mastering focus goes beyond understanding basic autofocus and manual adjustments. Advanced techniques allow photographers to tackle complex scenes, manage difficult lighting, and ensure their images communicate the intended story. These techniques are especially important when shooting in dynamic environments or when precision is critical, such as in macro, architecture, or event photography.

Focus stacking is a widely used advanced technique. This involves capturing multiple images of the same scene, each with the focus set at a different distance, and merging them in post-processing. The result is an image with an extended depth of field, where both foreground and background appear sharp. This method is essential in macro photography, where extreme close-ups typically have very shallow depth of field, and in landscape photography with intricate foreground elements.

Another technique is zone focusing, which involves pre-setting a focus distance and relying on depth of field to capture subjects within a specific range. This is particularly useful in street photography, where subjects move unpredictably and the photographer must anticipate the action. By estimating the distance and aperture required, zone focusing allows sharp images without relying on autofocus, which may be too slow for fast-moving scenes.

Pre-Focusing for Fast Action

Pre-focusing is an essential strategy for shooting fast action, such as sports, wildlife, or children at play. Instead of waiting for the camera to lock focus at the moment of action, the photographer estimates the area where the subject will enter the frame and sets focus in advance. This allows the shutter to capture the moment immediately, reducing the risk of missed opportunities.

Using continuous autofocus in combination with pre-focusing enhances this approach. The photographer can track the general path of the subject while keeping the focus point ready, improving the likelihood of sharp results. Burst mode further increases the chance of capturing the ideal frame. Combining pre-focusing, tracking, and rapid shooting creates a reliable workflow for challenging action scenes.

Focus in Low Light Conditions

Shooting in low light is one of the most common situations where focus becomes difficult. Cameras may struggle to acquire focus due to reduced contrast, and shallow depth of field increases the risk of missed sharpness. To overcome these challenges, photographers can use wider apertures, higher ISO settings, or assistive lighting, such as LED panels or flash.

Manual focus is particularly valuable in low-light scenarios. By using live view with magnification or focus peaking, the photographer can confirm precise focus even when autofocus is unreliable. Tripods and remote shutters help reduce camera shake, allowing slower shutter speeds without sacrificing sharpness. Understanding the interaction between focus, exposure, and lighting ensures better results when working under challenging conditions.

Managing Focus Across Mixed Subjects

When photographing scenes with multiple subjects or elements at different distances, choosing the right focus point becomes more complex. In these situations, photographers must consider depth of field, aperture, and subject importance. Wide apertures isolate a subject but may result in other elements being out of focus. Smaller apertures expand the depth of field but require careful control of shutter speed and ISO.

Techniques like selective focus and focus bracketing help manage mixed subjects. Focus bracketing is similar to focus stacking but can be applied dynamically for scenes with varying distances. It allows photographers to capture the entire subject range with precise sharpness, merging the images afterward. This is particularly effective in event photography, architectural photography, and group portraits where multiple planes of interest exist.

Common Focus Mistakes to Avoid

Several common mistakes can reduce the effectiveness of focus in photography. One of the most frequent errors is relying on autofocus without understanding its limitations. Autofocus can struggle in low contrast, low light, or reflective conditions, resulting in missed sharpness. Understanding when to switch to manual focus, use focus lock, or adjust focus points is critical.

Another mistake is ignoring the importance of depth of field. Using a wide aperture without considering the subject’s distance from the camera can lead to unintended blur in key areas. Conversely, using a very small aperture without compensating for light conditions can result in motion blur or noise due to slower shutter speeds and higher ISO.

Shifting focus after composing the image without locking can also cause unintended blur. When recomposing, photographers must either use focus lock or adjust focus to maintain clarity on the primary subject. Additionally, neglecting to check focus after capturing the image is a common oversight. Reviewing images on the camera’s display or through live view ensures that sharpness has been achieved before leaving the scene.

Focus and Lens Considerations

Lenses significantly affect how focus behaves in a photograph. Prime lenses typically offer sharper results and wider apertures, allowing for better control of depth of field. Zoom lenses provide versatility in composition but may require more attention to maintaining focus across different focal lengths. Understanding a lens’s characteristics, such as focus breathing or minimum focusing distance, helps photographers anticipate and adjust their focus strategies.

Macro lenses, telephoto lenses, and wide-angle lenses each present unique challenges. Macro lenses require extreme precision due to the shallow depth of field. Telephoto lenses magnify subject movement and camera shake, making stabilization and focus tracking critical. Wide-angle lenses offer extensive depth of field but may exaggerate perspective, requiring careful attention to foreground elements to maintain balance.

Focus on Dynamic and Environmental Conditions

Environmental factors, such as wind, rain, fog, or crowded locations, can complicate focus. Moving elements in the foreground or background can distract autofocus systems, and low contrast or haze can reduce the effectiveness of focus points. Photographers must adapt by pre-focusing, using manual adjustments, or adjusting aperture and shutter speed to maintain clarity.

In dynamic environments, anticipation and observation are as important as technical settings. Watching the movement of subjects, understanding patterns, and positioning the camera strategically allow photographers to capture sharp images despite unpredictable conditions. Combining these strategies with advanced focus techniques increases the likelihood of successful shots in challenging environments.

Using Focus Creatively

Focus is not only a technical tool but also a creative instrument. Deliberate decisions about what is sharp and what is blurred can enhance storytelling and visual impact. Shallow depth of field isolates subjects, creating emphasis and mood. Background blur or bokeh can add aesthetic value and draw attention to the main subject. Conversely, maintaining sharpness across an entire scene conveys scale, detail, and immersion.

Creative focus can also guide the viewer’s eye. Photographers can intentionally place focus on secondary elements to tell a more nuanced story or evoke emotion. Understanding how viewers interpret focus and sharpness allows for intentional manipulation, adding depth and meaning to images beyond technical precision.

Reviewing and Adjusting Focus

Even with careful planning, photographers should review their images critically. Checking focus on a camera’s display or using magnified previews ensures that critical areas are sharp. If adjustments are needed, capturing additional frames or tweaking settings can prevent missed opportunities. Consistent review builds awareness of focus performance and improves skill over time.

Post-processing tools can enhance focus, but they cannot fully replace correct in-camera technique. Sharpening filters, focus stacking, and selective adjustments are useful for refinement, but starting with precise focus is essential for the best results.

Practical Strategies for Maintaining Focus in the Field

Achieving precise focus consistently in the field requires a combination of preparation, awareness, and technique. Every shooting environment presents unique challenges, whether it is rapidly changing lighting, moving subjects, or crowded locations. Developing a workflow that prioritizes focus ensures that photographers capture images that are sharp and compelling.

Before entering any scene, it is important to assess the environment and anticipate potential difficulties. Consider the subject, distance, movement, and available light. Identifying these factors early allows photographers to adjust camera settings and focus techniques proactively rather than reactively. Preparation reduces stress, minimizes errors, and improves the likelihood of capturing the desired shot on the first attempt.

Setting Up Your Camera for Accurate Focus

Modern cameras offer a variety of focus modes and customization options. Understanding these settings is essential to achieving reliable sharpness. For stationary subjects, single-point autofocus or manual focus is typically the most precise. For moving subjects, continuous autofocus with tracking capabilities helps maintain sharpness as the subject moves through the frame.

Choosing the appropriate focus point is equally important. Center-focused points are often the most accurate, but moving the point to align with your subject ensures that the focus is exactly where it needs to be. Many cameras allow photographers to select focus points manually, which provides control and prevents the autofocus system from locking onto unintended elements in the frame.

Aperture selection is also critical. Wider apertures create a shallow depth of field, isolating the subject but requiring precise focus. Smaller apertures increase the depth of field, which is useful in landscapes, still life, or group portraits, but necessitates slower shutter speeds or higher ISO settings. Understanding the relationship between aperture, shutter speed, and focus helps maintain clarity across diverse shooting conditions.

Using Autofocus Effectively

Autofocus is a powerful tool when used correctly, but misuse can result in blurry or misplaced focus. To optimize autofocus, understand the camera’s capabilities and limitations. Continuous autofocus is ideal for subjects that move unpredictably, such as wildlife or sports, while single-shot autofocus works best for static subjects.

Tracking modes provide additional support for dynamic scenes. These systems detect subject movement and adjust focus automatically, increasing the likelihood of sharp images even if the subject is moving quickly. Combining tracking with burst mode allows photographers to capture multiple frames in rapid succession, ensuring that at least one frame achieves perfect focus.

Manual Focus and Focus Assistance

Manual focus remains invaluable in situations where autofocus may struggle. Low light, low contrast, reflective surfaces, or intricate details often confuse autofocus systems. Using live view with magnification or focus peaking assists in verifying precise focus. These tools highlight the areas of sharpest detail, making it easier to adjust manually.

Manual focus is especially effective in controlled scenarios such as studio, product, or macro photography. Photographers can take the time to refine focus without pressure, ensuring that critical areas remain crisp. Practicing manual focus also improves overall understanding of depth of field, lens behavior, and camera ergonomics.

Focus Bracketing and Stacking

Focus bracketing and stacking are advanced but practical techniques for achieving extensive sharpness across complex scenes. Focus bracketing involves capturing multiple images with incremental adjustments to the focal plane, which are then merged in post-processing. This ensures that every element, from foreground to background, appears sharp.

Focus stacking is particularly beneficial in macro photography, product shoots, and intricate landscapes. Close-up images typically have extremely shallow depth of field, making it difficult to maintain sharpness across the entire subject. By stacking images, photographers can create a single frame where every element is clear and detailed, improving the visual impact and professionalism of the final image.

Anticipating and Adjusting for Movement

In dynamic environments, anticipating subject movement is key. Observing patterns, such as a bird’s flight path, an athlete’s stride, or a child’s play behavior, allows pre-focusing and timely shutter release. Predictive techniques increase the likelihood of capturing sharp images despite unpredictable motion.

Adjusting focus for moving subjects also involves balancing shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. Faster shutter speeds freeze motion, but may require higher ISO or wider apertures in low light. Photographers must make deliberate trade-offs to maintain both focus and exposure, ensuring that the final image is clear and visually engaging.

Managing Focus in Challenging Lighting Conditions

Lighting significantly impacts focus. Low light reduces contrast, which can make autofocus unreliable, while harsh or uneven light may create glare or shadows that interfere with accuracy. Photographers must adapt by using manual focus, selecting appropriate focus points, and adjusting camera settings.

Supplemental lighting can assist in maintaining focus. Continuous lights, reflectors, or flash units provide additional illumination, improving contrast and making autofocus more effective. Understanding how light interacts with the subject and the scene ensures that focus is achieved accurately in all conditions.

Techniques for Depth of Field Control

Controlling depth of field is essential for effective focus management. Shallow depth of field isolates subjects, creating emphasis and guiding the viewer’s attention. Wide depth of field ensures clarity across the frame, which is particularly useful in landscapes, architectural photography, and group shots.

Hyperfocal distance is a valuable tool for maximizing depth of field in wide scenes. By focusing on the hyperfocal distance, photographers can achieve optimal sharpness from a specific foreground point to infinity. Calculators, charts, and live view magnification can help determine the correct distance for any given aperture and focal length.

Reviewing and Adjusting Focus in the Field

Regularly reviewing images during a shoot is crucial. Checking focus on the camera’s display or through live view magnification ensures that critical areas are sharp. Adjustments can then be made immediately, preventing missed opportunities.

In challenging conditions, taking multiple shots at slightly different focus points provides flexibility. This approach, often combined with burst mode or focus bracketing, increases the probability of achieving perfect sharpness. Developing a habit of reviewing and adjusting focus improves consistency and confidence over time.

Workflow Techniques for Focus Consistency

Establishing a systematic workflow helps maintain focus and consistency. Begin by analyzing the scene, selecting the appropriate focus mode, choosing the correct aperture, and positioning the focus point strategically. Confirm focus using live view, peaking, or magnification tools before taking the shot.

During the shoot, periodically reassess focus based on subject movement, lighting changes, or compositional adjustments. Use burst mode or multiple frames when necessary, and take advantage of post-processing techniques like focus stacking for complex scenes. By following a disciplined workflow, photographers reduce errors and improve overall image quality.

Focus on Creative Composition

Beyond technical accuracy, focus serves a creative function. Intentional decisions about what is sharp and what is blurred guide the viewer’s eye and emphasize narrative elements. Shallow depth of field isolates subjects, enhancing emotional impact, while broad focus conveys detail, scale, and context.

Creative focus can also direct attention toward secondary elements, create visual layers, or suggest movement. Combining focus techniques with composition, lighting, and color enhances storytelling and transforms technically sharp images into visually compelling narratives.

Avoiding Common Focus Pitfalls

Even experienced photographers can fall into focus-related pitfalls. Relying too heavily on autofocus without understanding limitations, neglecting depth of field, and failing to pre-focus for action are common mistakes. In addition, ignoring environmental factors, such as low light, reflective surfaces, or obstructed subjects, can reduce image clarity.

Recomposition without focus adjustment, using excessively wide apertures in complex scenes, and neglecting to review images also contribute to focus errors. Awareness of these pitfalls and developing strategies to mitigate them ensures consistent sharpness across different shooting conditions.

Field Tips for Everyday Photography

For everyday photography, practical field strategies simplify focus management. Observing your subject, anticipating movement, and choosing the appropriate focus mode are fundamental steps. Use the camera’s focus points effectively, lock focus when recomposing, and verify sharpness in the viewfinder or on the LCD.

Carrying a tripod or stabilizing the camera reduces motion blur, particularly in low-light or long-exposure scenarios. Combining stabilization with proper focus techniques ensures that images are sharp without compromising composition or creativity.

For unpredictable scenes, burst mode and continuous autofocus offer flexibility. Taking multiple shots increases the likelihood of capturing the perfect frame, while pre-focusing allows quick reaction to dynamic subjects. Developing a habit of assessing the scene and planning focus decisions improves efficiency and image quality in real-world shooting.

Final Tips for Achieving Perfect Focus

Achieving perfect focus consistently requires a combination of knowledge, skill, and practice. While understanding camera settings, autofocus modes, and manual focus techniques is fundamental, integrating these elements into a coherent workflow is what ensures reliable results. Perfect focus transforms ordinary photographs into striking images that convey clarity, emotion, and narrative.

One of the most important final tips is to always prioritize the subject. Identifying the critical area that must remain sharp allows you to make informed decisions about focus points, aperture, and shutter speed. In portraits, this is typically the eyes. In wildlife photography, it may be the head or main body of the animal. In landscapes, it is often the primary subject or the midground when the scene is wide and complex. Recognizing the focal priority ensures that the most visually significant elements remain crisp.

Troubleshooting Focus Issues

Even with careful planning, focus issues can arise. One common problem is that the camera consistently fails to lock onto the intended subject. This often occurs in low-contrast situations, low light, or when reflective surfaces are present. Switching to manual focus or using live view magnification and focus peaking can resolve these issues.

Back or front focusing, where the camera focuses slightly in front of or behind the subject, is another frequent challenge. This can be addressed by calibrating the lens, using focus fine-tuning features if available, or employing precise manual adjustments. Checking results frequently ensures that minor deviations are corrected before they compromise multiple shots.

Motion blur caused by camera shake or subject movement is often mistaken for focus errors. While technically not a focus problem, the effect is the same: the image appears soft. Using faster shutter speeds, stabilizing the camera with a tripod, or employing image stabilization features can mitigate this issue. Understanding the interaction between shutter speed, focal length, and movement is essential for achieving apparent sharpness.

Integrating Focus into a Complete Workflow

Focus should not be treated in isolation but integrated into a complete photography workflow. Begin with pre-visualization of the scene or subject, considering composition, lighting, and movement. Determine the primary focal point and select the appropriate focus mode and focus point on your camera.

Next, choose the aperture based on the desired depth of field. For a shallow depth of field, prioritize the subject by placing the focus on the critical area. For extensive depth of field, ensure that the selected focus point allows both foreground and background elements to appear sharp. Adjust shutter speed and ISO to maintain correct exposure without compromising sharpness.

During shooting, continuously monitor focus. Use live view magnification, focus peaking, or electronic viewfinder tools when available. Take multiple frames if necessary, especially for moving subjects or scenes with multiple planes of interest. Post-processing should complement, not replace, in-camera focus precision. Techniques like focus stacking, sharpening, and selective adjustments enhance the final image while preserving natural appearance.

Focusing on Different Genres Simultaneously

Many photographers encounter scenarios where multiple genres overlap. For instance, an outdoor portrait may include landscape elements, or a wildlife scene may feature both fast-moving animals and a detailed environment. Integrating focus techniques for such complex situations requires strategic planning.

One approach is to prioritize the subject that carries the main visual or emotional weight. Set the focus on that element while adjusting the aperture to balance the secondary areas. If both foreground and background require sharpness, consider focus stacking or using a smaller aperture while compensating with higher ISO or slower shutter speeds. Understanding the interplay of depth, movement, and light allows photographers to maintain sharpness across mixed genres.

Environmental Awareness and Focus

Environmental conditions can influence focus more than most photographers anticipate. Wind can move leaves, flowers, or foreground elements, creating unintended blur. Low light reduces autofocus reliability, while haze, fog, or glare can interfere with accurate focus acquisition.

Adapting to environmental factors requires observation and flexibility. Adjusting camera position, using manual focus, or waiting for optimal light and conditions ensures clarity. In fast-paced scenarios, photographers must make quick, informed decisions about where and how to focus, balancing technical constraints with artistic intent.

Maintaining Focus with Moving Subjects

Dynamic subjects, such as athletes, animals, or children, present consistent challenges. Continuous autofocus, tracking modes, and burst shooting are invaluable tools for maintaining focus in these situations. Anticipation plays a crucial role: observing movement patterns and predicting where the subject will be allows pre-focusing or strategic placement of focus points.

Shutter speed must complement the focus technique. Freezing motion reduces the chance of blur, while slower shutter speeds can introduce artistic motion effects without compromising the focal plane if movement is primarily in background elements. Choosing the correct balance between motion capture and sharpness is key to successful dynamic photography.

Creative Focus Applications

Beyond technical precision, focus serves a creative purpose. Deliberate decisions about what to keep sharp and what to blur guide viewer attention, enhance storytelling, and add depth to images. Shallow depth of field isolates subjects, creating intimacy or drama, while broader depth of field emphasizes detail and context.

Selective focus can draw attention to specific aspects of a scene, such as textures, patterns, or secondary subjects. Foreground or background blur can create layers within the image, leading the viewer’s eye through the composition deliberately and engagingly. Mastering both technical and creative applications of focus elevates photography from simple documentation to expressive artistry.

Focus Calibration and Equipment Maintenance

Proper camera and lens maintenance is critical for reliable focus. Lens calibration ensures that autofocus systems function accurately, particularly with telephoto or high-performance lenses. Regularly cleaning lenses, sensors, and viewfinders prevents dust or debris from interfering with focus performance.

Firmware updates for cameras and lenses often include improvements to autofocus performance. Staying current with updates ensures that focus systems operate efficiently and reliably. Understanding your equipment’s strengths and limitations allows you to anticipate potential challenges and adjust techniques accordingly.

Post-Processing Considerations

Post-processing can enhance focus and sharpness,, but is not a substitute for accurate in-camera focus. Sharpening tools, selective clarity adjustments, and focus stacking techniques can improve perceived sharpness and correct minor issues. However, images captured with incorrect focus often cannot be fully corrected digitally.

When combining multiple images for focus stacking, careful alignment and blending are necessary to maintain a natural appearance. Overuse of sharpening tools can create artifacts or unnatural textures. Applying post-processing techniques as a complement to solid in-camera focus ensures that the final image is both precise and visually appealing.

Developing Consistency and Intuition

Consistent focus requires practice, observation, and habit. By repeatedly applying focus techniques, reviewing results, and refining workflows, photographers develop intuition for determining optimal focus points, aperture settings, and shutter speeds.

Field experience enhances the ability to anticipate movement, assess environmental conditions, and make quick decisions. Over time, this intuition allows photographers to achieve reliable sharpness even in unpredictable or complex scenarios. Developing a systematic approach while remaining adaptable ensures that focus remains effective across all genres and situations.

Integrating Focus with Composition and Storytelling

Focus is not an isolated technical consideration; it is integral to composition and storytelling. The focal point guides the viewer’s eye, emphasizes key elements, and supports the narrative of the image. Proper use of focus reinforces compositional choices, such as leading lines, framing, and perspective, creating images that are both visually and emotionally compelling.

In multi-subject or layered scenes, focus helps establish hierarchy, distinguishing primary subjects from secondary elements. Strategic placement of sharp areas and controlled blur directs attention and enhances clarity. Combining focus with composition ensures that the viewer’s eye moves naturally through the image, engaging with the intended story.

Field Workflow for Optimal Focus

A practical workflow begins with analyzing the scene or subject, identifying the primary focal point, and selecting the appropriate focus mode. Adjust the aperture for the desired depth of field, and set the shutter speed and ISO to maintain proper exposure. Confirm focus using live view, magnification, or focus peaking, and take multiple frames if necessary.

During the shoot, continually monitor focus, particularly in dynamic or changing conditions. Adjust settings in response to movement, light, or environmental factors. Post-processing can refine and enhance sharpness, but the foundation is reliable in-camera focus. A disciplined workflow ensures consistent results, reduces errors, and increases confidence in field photography.

Conclusion

Mastering focus is both a technical and creative endeavor. It requires understanding camera systems, lenses, depth of field, and environmental factors, while also integrating focus decisions into composition and storytelling. Advanced techniques like focus stacking, pre-focusing, and selective focus expand creative possibilities, while consistent practice and workflow refinement ensure reliable results.

Avoiding common pitfalls, troubleshooting effectively, and maintaining equipment contribute to focus accuracy. Creative application enhances narrative and visual impact, transforming technically sharp images into compelling works of art.

By combining preparation, observation, technique, and creativity, photographers achieve mastery over focus. This skill enables them to capture sharp, engaging, and meaningful images across all genres, from landscapes and wildlife to portraits and product photography. Focus becomes both a foundation and a tool, guiding the viewer’s attention, conveying emotion, and telling a story with clarity and precision.

Mastering focus ultimately elevates photography, transforming it from simple documentation into expressive visual communication that resonates with viewers. Consistency, practice, and thoughtful integration of focus techniques are essential for any photographer seeking to produce high-quality, professional images in all circumstances.