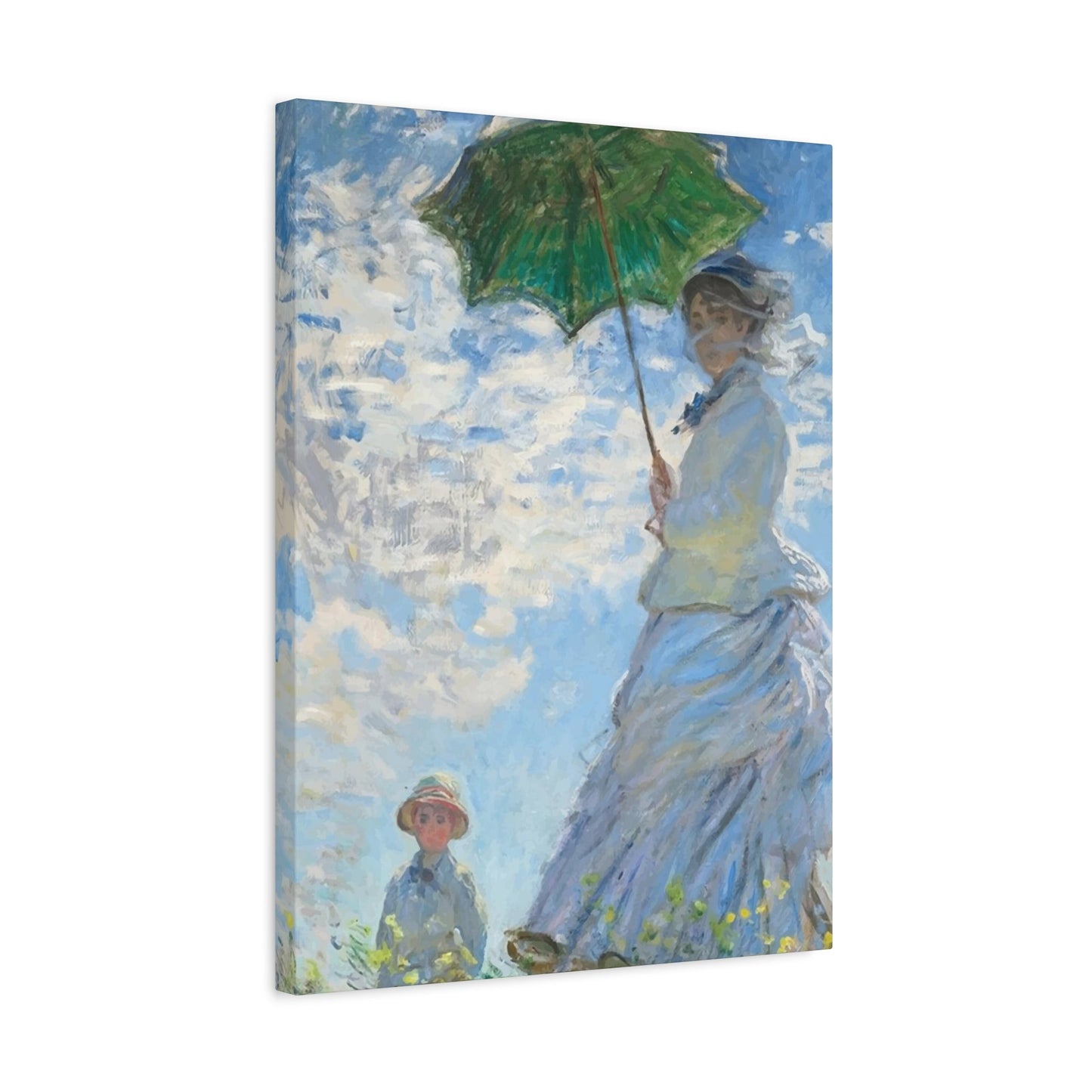

Impressionism Wall Art & Canvas Prints

Impressionism Wall Art & Canvas Prints

Couldn't load pickup availability

The Enchanting World of Impressionism Wall Art: A Journey Through Color, Light, and Emotion

Impressionism stands as one of history's most beloved and revolutionary artistic movements, fundamentally transforming how we perceive and appreciate visual art. This extraordinary movement emerged in the 19th century, challenging conventional artistic norms and introducing a fresh perspective on capturing light, color, and emotion. When we explore impressionist wall art today, we're not just decorating our homes – we're bringing centuries of artistic innovation and emotional depth into our daily lives.

The world of impressionist wall art offers an unparalleled opportunity to connect with some of humanity's greatest artistic achievements while creating environments that inspire, soothe, and energize. From the gentle water lilies of Claude Monet to the vibrant café scenes of Auguste Renoir, impressionist pieces bring a unique combination of technical mastery and emotional resonance that continues to captivate viewers more than a century after their creation.

Understanding impressionist wall art requires delving into the rich history, techniques, and cultural impact of this movement. Each brushstroke tells a story, each color choice reflects a moment in time, and each composition captures the fleeting beauty of natural light and human emotion. Whether you're a seasoned art collector or someone just beginning to appreciate the beauty of impressionist works, this comprehensive exploration will guide you through every aspect of this magnificent artistic tradition.

The Historical Genesis of the Impressionist Movement

The impressionist movement emerged during a period of tremendous social and technological change in 19th century France. The Industrial Revolution was transforming urban landscapes, new transportation systems were making travel more accessible, and scientific discoveries were revolutionizing understanding of light and color. Against this backdrop of change, a group of revolutionary artists began questioning the rigid academic traditions that had dominated European art for centuries.

Traditional academic painting emphasized historical and mythological subjects, precise drawing, and carefully controlled lighting in studio settings. Artists were expected to create highly finished works with smooth surfaces and invisible brushstrokes. The Salon, France's official art exhibition, served as the primary arbiter of artistic taste and success, typically favoring works that adhered to these established conventions.

However, a new generation of artists began experimenting with different approaches to capturing reality. They were inspired by scientific research into color theory and optics, particularly the work of scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood, who studied how colors interact and influence human perception. These scientific insights would later inform the impressionists' innovative use of color and light.

The invention of portable paint tubes in 1841 proved revolutionary for artists seeking to work outdoors. Previously, artists had to mix their pigments in studios, making outdoor painting cumbersome and impractical. With ready-made paints in convenient tubes, artists could venture into nature with their easels, capturing the changing qualities of natural light throughout the day.

Photography's emergence in the mid-19th century also influenced impressionist thinking. As cameras began capturing realistic images with unprecedented accuracy, artists questioned whether painting needed to serve the same documentary function. This technological development freed artists to explore more interpretive and expressive approaches to representing reality.

The political and social upheavals of the period, including the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, created an atmosphere of questioning established authority and seeking new forms of expression. Artists increasingly sought to capture the modern world around them rather than retreating into idealized historical or mythological subjects.

Economic factors also played a role in impressionism's development. The growing middle class created new markets for art, while the expansion of railroad networks made it easier for artists to travel to rural locations for painting. Urban development in Paris under Baron Haussmann created new boulevards and public destinations that became favorite subjects for impressionist painters.

The café culture that flourished in 19th century Paris provided informal meeting places where artists could discuss their ideas and develop their aesthetic theories. These gatherings fostered the collaborative spirit that would characterize the impressionist movement, as artists shared techniques, critiqued each other's work, and planned exhibitions outside the established Salon system.

Pioneering Artists Who Defined Impressionist Expression

Claude Monet stands as perhaps the most recognizable figure in impressionist art, often credited with giving the movement its name through his painting "Impression, Sunrise." Monet's dedication to capturing the effects of natural light led him to create series of paintings depicting the same subject under different lighting conditions. His water lily paintings, created in his garden at Giverny, demonstrate his mastery of color and light while exploring themes of reflection, transparency, and the passage of time.

Monet's approach to wall art was revolutionary in its emphasis on the sensory experience of viewing art. Rather than focusing on precise details or narrative content, he sought to create paintings that would evoke the feeling of being present in a particular moment and location. His brushwork became increasingly loose and expressive throughout his career, with individual strokes of color working together to create shimmering effects that seemed to capture the very essence of light itself.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir brought a distinctly humanistic approach to impressionism, focusing on portraits and scenes of social life. His paintings radiate warmth and joy, often depicting friends and family in relaxed, natural poses. Renoir's handling of paint was particularly innovative, using broken color and visible brushstrokes to create surfaces that seem to glow with inner light. His portraits demonstrate how impressionist techniques could be applied to figure painting while maintaining the movement's emphasis on natural light and color.

Edgar Degas, though often associated with impressionism, maintained a more structured approach to composition while embracing many of the movement's innovations. His paintings and pastels of dancers, horse races, and café scenes show remarkable skill in capturing movement and the effects of artificial lighting. Degas was particularly interested in unusual viewpoints and cropping, techniques that may have been influenced by photography but were applied with distinctly artistic sensibilities.

Camille Pissarro served as something of a mentor figure within the impressionist group, participating in all eight of the independent exhibitions organized by the impressionists. His landscapes demonstrate a particular sensitivity to rural life and agricultural themes, while his later work explored the pointillist techniques developed by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Pissarro's dedication to plein air painting helped establish outdoor work as a fundamental aspect of impressionist practice.

Berthe Morisot, one of the few women among the core group of impressionist painters, brought a unique perspective to the movement. Her paintings often depicted domestic scenes and family life, subjects that were considered appropriate for women artists at the time. However, her technical skill and innovative use of color and brushwork were equal to any of her male contemporaries. Morisot's work demonstrates how impressionist techniques could be applied to intimate subjects while maintaining the movement's revolutionary approach to painting.

Mary Cassatt, an American artist who moved to Paris and became associated with the impressionists, specialized in paintings of women and children. Her work shows the influence of Japanese prints in its use of bold outlines and flattened forms, combined with impressionist color and brushwork. Cassatt's paintings offer insight into late 19th century domestic life while demonstrating the international appeal of impressionist techniques.

Gustave Caillebotte, often overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries, created some of the most technically accomplished impressionist paintings. His urban scenes of Paris show remarkable skill in depicting reflections, rain effects, and the play of light on various surfaces. Caillebotte's work also demonstrates the movement's engagement with modern urban life and its embrace of contemporary subject matter.

The Revolutionary Approach to Light and Color

The impressionist approach to light and color represented a fundamental departure from traditional painting methods. Rather than viewing light as a means of revealing form and detail, impressionist artists began to see light itself as their primary subject matter. This shift required developing entirely new painting techniques and color theories that would influence artistic practice for generations to come.

Traditional academic painting relied on careful modeling with light and shadow to create the illusion of three-dimensional form on a flat surface. Artists mixed colors on their palettes to match the perceived colors of objects, often using earth tones and subdued palettes to create harmonious compositions. Shadows were typically painted in browns and grays, while highlights used white or very light versions of the base colors.

Impressionist artists revolutionized this approach by observing that shadows are rarely neutral gray or brown but instead contain reflected colors from surrounding objects and the sky. They noticed that snow in shadow often appears blue due to reflected skylight, while shadows on warm-colored objects might contain complementary cool tones. This observation led to the impressionist practice of using color contrasts to create the sensation of light rather than relying solely on value contrasts.

The broken color technique became a hallmark of impressionist painting. Instead of mixing colors thoroughly on the palette, artists began applying separate touches of pure color directly to the canvas, allowing the viewer's eye to optically mix these colors at a distance. This technique created more vibrant color effects than traditional mixing methods and gave impressionist paintings their characteristic shimmering quality.

Scientific color theory played an important role in impressionist development. The work of Michel Eugène Chevreul on simultaneous contrast showed how colors appear different depending on their surroundings, while Ogden Rood's studies of additive and subtractive color mixing provided theoretical support for broken color techniques. These scientific insights helped impressionist artists understand why their intuitive approaches to color were so effective.

The impressionist palette underwent significant changes from traditional academic practices. Artists began using brighter, purer pigments and avoided mixing colors to muddy neutrals. The development of new synthetic pigments like chrome yellow, ultramarine blue, and cadmium colors provided impressionists with more brilliant and stable colors than had been available to earlier artists. This expanded palette enabled the creation of more vibrant and luminous paintings.

Complementary color relationships became central to impressionist color theory. Artists learned to place complementary colors adjacent to each other to create vibrant effects and to use warm and cool color contrasts to suggest advancing and receding forms. Orange and blue, red and green, yellow and purple – these complementary pairs appear throughout impressionist paintings, creating dynamic color relationships that energize the entire composition.

The treatment of white in impressionist painting also differed significantly from traditional methods. Rather than using white straight from the tube, impressionist artists mixed white with small amounts of other colors to create warm or cool variations. Snow might be painted with blue-white, pink-white, or yellow-white depending on the lighting conditions and time of day. This approach to white contributed to the overall color harmony of impressionist paintings while maintaining their luminous quality.

Atmospheric perspective received new interpretation in impressionist hands. Traditional landscape painting used cooler, lighter colors to suggest distant forms, but impressionist artists observed that atmospheric conditions could dramatically alter these relationships. Morning mist might warm distant colors, while certain lighting conditions could intensify colors in the distance. These observations led to more nuanced and naturalistic treatments of atmospheric effects.

Distinguishing Impressionism From Realist Traditions

The relationship between impressionism and realism reveals important distinctions in artistic philosophy and technique that help define what made the impressionist approach so revolutionary. While both movements sought to depict contemporary life rather than historical or mythological subjects, their methods and ultimate goals differed significantly.

Realist painters like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet focused on social themes and working-class subjects, seeking to present unidealized views of contemporary life. Realist paintings often carried implicit or explicit social commentary, depicting the struggles and dignity of common people. The technique remained relatively traditional, with careful drawing, controlled brushwork, and attention to accurate detail serving the goal of clear communication.

Impressionist artists, while also interested in contemporary subjects, were more concerned with the sensory experience of perception than with social commentary. They painted the same middle-class leisure activities and urban scenes that surrounded their own lives, but their primary focus was on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere rather than making social or political statements.

The treatment of detail provides another key distinction between these movements. Realist painters typically included sufficient detail to clearly identify objects, people, and settings. Even when working with broad brushstrokes, realist artists maintained enough descriptive information to support their narrative or social themes. Impressionist artists often sacrificed descriptive detail in favor of overall visual effects, allowing forms to dissolve into patterns of color and light.

Brushwork techniques differed markedly between these approaches. Realist painters generally sought to minimize the visibility of individual brushstrokes, creating smooth surfaces that wouldn't distract from the subject matter. When visible brushwork was employed, it usually followed the forms of objects being depicted. Impressionist brushwork became increasingly independent of descriptive function, with strokes of color serving primarily to create optical effects and surface textures.

The concept of finish also distinguished these movements. Academic and realist traditions valued highly finished works with carefully resolved details and smooth transitions between colors and tones. Impressionist paintings often retained the spontaneous quality of sketches, with areas of bare canvas visible and individual brushstrokes clearly evident. This apparent lack of finish initially shocked viewers accustomed to more polished academic work.

Subject matter choices reflected different priorities in these movements. Realist painters often selected subjects that would highlight social inequalities or celebrate the dignity of labor. They painted peasants, workers, and scenes of rural poverty with the intention of raising awareness about contemporary social conditions. Impressionist artists typically focused on pleasant leisure activities, beautiful landscapes, and decorative subjects that emphasized aesthetic rather than social concerns.

The working methods of these movements also differed significantly. Realist painters typically worked in studios, making preparatory studies and developing compositions through traditional academic methods. They might work outdoors to gather information but would usually complete major works in controlled studio environments. Impressionist artists increasingly worked outdoors, completing paintings in direct response to natural lighting conditions and weather.

Color theory applications reveal another distinction between these approaches. Realist painters used color primarily to accurately represent the local colors of objects under standard lighting conditions. While they might observe color changes due to lighting, their goal was usually to present recognizable, naturalistic color relationships. Impressionist artists used color expressively, exploring how unusual lighting conditions and atmospheric effects could create unexpected and beautiful color combinations.

The intended audience and exhibition strategies of these movements reflected their different goals. Realist painters typically sought acceptance in official exhibitions like the Salon, where their social themes might reach influential viewers and create discussion about contemporary issues. Impressionist artists often exhibited independently, seeking viewers who were interested in aesthetic innovation rather than social commentary.

Masterpieces That Define Impressionist Legacy

The canon of impressionist masterpieces encompasses a remarkable range of subjects and techniques, each contributing to our understanding of what made this movement so influential and enduring. These paintings continue to attract viewers more than a century after their creation, demonstrating the timeless appeal of impressionist innovations in capturing light, color, and emotion.

Claude Monet's "Water Lilies" series represents one of the most ambitious projects in art history, spanning nearly three decades of the artist's career. These paintings explore the reflective surface of the lily pond at Monet's Giverny garden, showing how changing light throughout the day and seasons could transform the same subject into countless different visual experiences. The larger panels, particularly those installed in the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris, create immersive environments that surround viewers with shimmering color and light. When considering these works as wall art, they demonstrate how impressionist paintings can transform architectural environments and create contemplative atmospheres.

Monet's "Rouen Cathedral" series illustrates the impressionist fascination with light's transformative power. By painting the same Gothic façade at different times of day, Monet revealed how light could completely alter the appearance of solid stone architecture. Morning light creates cool, ethereal effects, while afternoon sun transforms the cathedral into warm golden tones. Evening light brings rich purples and deep blues into the stone surfaces. These paintings show how impressionist wall art can capture not just appearance but the passage of time itself.

Auguste Renoir's "Luncheon of the Boating Party" combines portraiture, still life, and landscape elements in a complex composition that demonstrates the versatility of impressionist techniques. The painting depicts a leisurely afternoon gathering at a riverside restaurant, with dappled sunlight filtering through awnings and reflecting off water surfaces. The warm palette and loose brushwork create an atmosphere of relaxed conviviality that exemplifies the impressionist celebration of modern leisure activities.

Renoir's "Dance at Moulin de la Galette" captures the energy and movement of Parisian social life through innovative use of broken color and dynamic brushwork. The painting shows couples dancing and socializing in the dappled light filtering through tree leaves, creating a complex pattern of light and shadow across the figures. The work demonstrates how impressionist techniques could be applied to complex multi-figure compositions while maintaining the movement's emphasis on natural lighting effects.

Edgar Degas's "The Ballet Rehearsal" series showcases the artist's unique perspective on movement and artificial lighting. These paintings often show dancers from unusual angles, capturing them in moments of preparation rather than performance. Degas's pastel technique creates soft, luminous effects that seem perfectly suited to the delicate subject matter. The compositions often use dramatic cropping and asymmetrical arrangements that create dynamic tensions within the pictorial field.

Degas's race track scenes demonstrate impressionist approaches to depicting speed and motion. Paintings like "Before the Race" capture horses and jockeys in moments of anticipation, using loose brushwork and strategic color placement to suggest nervous energy and movement. The artist's understanding of equine anatomy combined with impressionist color techniques creates powerful images of modern sporting events.

Camille Pissarro's "The Boulevard Montmartre" series shows how impressionist artists documented the transformation of Paris during the late 19th century. These paintings capture the bustling energy of modern urban life through techniques that emphasize movement and atmospheric effects. The series includes views in different weather conditions and times of day, showing how the same location could provide endless variations for artistic exploration.

Berthe Morisot's "The Cradle" demonstrates the intimate domestic subjects that became important themes in impressionist art. The painting shows a mother watching over her sleeping child, rendered with the soft brushwork and luminous palette characteristic of the movement. The work illustrates how impressionist techniques could be applied to traditional subjects while bringing new levels of emotional immediacy and natural observation.

Mary Cassatt's "The Child's Bath" exemplifies the artist's skill in combining impressionist color techniques with precise drawing and composition. The painting shows the influence of Japanese prints in its bold outlines and simplified forms, while the color palette and brushwork remain distinctly impressionist. The work demonstrates how international influences could be integrated with impressionist innovations to create new hybrid approaches.

Gustave Caillebotte's "Paris Street; Rainy Day" presents one of the most technically accomplished examples of impressionist urban painting. The work shows remarkable skill in depicting reflections on wet pavement and the effects of overcast lighting on urban architecture. The composition's careful geometric structure combines with impressionist color techniques to create a powerful image of modern city life.

Technical Methods and Painting Approaches

The technical innovations developed by impressionist artists fundamentally changed how paint could be applied to create visual effects. These methods, which initially shocked viewers accustomed to smooth academic finishes, proved extraordinarily influential and continue to inform contemporary painting practices. Understanding these techniques provides insight into how impressionist wall art achieves its distinctive visual qualities.

The alla prima technique became central to impressionist practice, particularly for outdoor painting. Rather than building up paintings in layers over extended periods, artists began completing works in single sessions while the paint remained wet. This approach allowed for more spontaneous color mixing directly on the canvas surface and created more immediate, fresh-looking results. The technique required careful planning and decisive execution, as artists had limited time to achieve their desired effects before the paint began to set.

Brushwork in impressionist painting served multiple functions beyond simply applying color to canvas. The direction, pressure, and texture of brushstrokes became expressive elements that could suggest movement, surface textures, and lighting conditions. Short, choppy strokes might suggest foliage or water surfaces, while longer, flowing strokes could indicate smooth surfaces or atmospheric effects. The visibility of individual brushstrokes, initially considered a sign of unfinished work, became celebrated as evidence of the artist's direct engagement with the subject.

The impressionist palette underwent significant organization to support rapid outdoor painting. Artists typically arranged pure colors around the edge of their palettes, avoiding pre-mixed neutrals that could muddy color relationships. White occupied a prominent position, as it was mixed with most other colors to create the light-filled effects characteristic of the movement. Earth tones were often eliminated entirely in favor of pure spectrum colors that could create more vibrant optical mixtures.

Color mixing techniques distinguished impressionist practice from traditional methods. Rather than thoroughly blending colors on the palette, artists began mixing colors optically by placing separate touches of pure color adjacent to each other on the canvas. This broken color approach created more vibrant results than physical mixing, as the eye blends pure colors more effectively than pigments can be mixed mechanically. The technique also allowed for more complex color relationships, as multiple colors could be perceived simultaneously in the same area.

The scumbling technique involved dragging dry paint over previously applied layers, allowing underlying colors to show through and create complex color relationships. This approach proved particularly effective for suggesting atmospheric effects, soft textures, and transitions between different areas of a painting. When applied with a dry brush over textured surfaces, scumbling could create sparkling light effects that perfectly suited impressionist goals.

Impasto application, where paint is applied thickly enough to retain the marks of the brush or painting knife, became increasingly important in later impressionist work. This technique created actual three-dimensional textures on the canvas surface, causing the paint itself to catch and reflect light. Heavy impasto areas could create focal points within compositions while suggesting the tactile qualities of different surfaces and materials.

The preparation of painting surfaces also evolved to support impressionist techniques. Many artists preferred canvas with visible texture, as the weave could catch and hold paint in ways that enhanced broken color effects. Some artists used colored grounds instead of traditional white preparations, allowing the ground color to influence the overall tonality of the finished painting. Toned grounds could provide unity to complex color schemes while reducing the amount of paint needed to cover the surface.

Painting knife techniques supplemented traditional brush methods, particularly for applying thick paint or creating specific textural effects. Artists like Paul Cézanne and later Vincent van Gogh used painting knives to create bold, geometric applications of color that could suggest architectural forms or strongly lit surfaces. The technique allowed for very direct paint application and could create effects impossible to achieve with brushes alone.

The timing of paint application became crucial in impressionist technique. Artists learned to work with varying degrees of paint wetness to achieve different effects. Painting into wet paint allowed for soft blending and gradual transitions, while painting on partially dry surfaces could create different textural qualities. The ability to control these variables required considerable experience and contributed to the distinctive surface qualities of impressionist paintings.

Varnishing and finishing practices also changed with impressionist innovations. Many impressionist paintings were left unvarnished or received only light, matte varnishes that wouldn't alter the color relationships or surface textures that were integral to their effects. This departure from traditional high-gloss finishes helped preserve the subtle color variations and broken brushwork that defined impressionist aesthetics.

The Natural World as Artistic Inspiration

The impressionist movement's relationship with nature represented a fundamental shift in how artists understood and depicted the natural world. Rather than viewing nature as a collection of objects to be accurately rendered, impressionist artists began seeing it as a continuously changing phenomenon of light, color, and atmospheric conditions. This new perspective transformed landscape painting and established approaches to natural subjects that continue to influence contemporary art.

The practice of plein air painting became central to impressionist engagement with nature. Artists ventured outdoors with portable easels, pre-stretched canvases, and organized paint boxes to capture natural lighting conditions directly from observation. This practice required adapting to changing weather, shifting light, and practical challenges of outdoor work, but it provided access to color relationships and atmospheric effects impossible to observe in studio settings.

Seasonal variations became important subjects for impressionist exploration. Artists like Claude Monet created series showing the same locations through different seasons, demonstrating how changing weather and light could completely transform familiar subjects. Snow scenes revealed the complex color relationships in white surfaces, while autumn paintings explored warm color harmonies and the effects of filtered light through colored foliage. Spring compositions celebrated renewal and fresh growth, while summer works captured the intensity of full sunlight and deep shadows.

Water became a particularly important subject for impressionist artists, offering opportunities to explore reflection, transparency, and movement. Rivers, ponds, and seascapes provided complex subjects that changed constantly with shifting light and weather conditions. Artists developed specialized techniques for depicting water surfaces, using horizontal brushstrokes to suggest calm water and broken, choppy strokes for rougher conditions. The interplay between reflected and transmitted light in water scenes created some of the most innovative color relationships in impressionist painting.

Garden subjects allowed impressionist artists to study cultivated nature under controlled conditions. Monet's garden at Giverny became a living laboratory for studying color relationships and seasonal changes. The water lily pond, with its carefully controlled lighting and diverse plant life, provided subjects for hundreds of paintings that explored the boundaries between representation and abstraction. Other artists created similar garden studies, using cultivated landscapes to explore specific color theories and painting techniques.

The treatment of sky and atmosphere in impressionist painting reflected new understanding of how weather conditions affect visual perception. Artists observed that sky colors change throughout the day and in different weather conditions, influencing the overall color temperature of entire landscapes. Cloud formations received careful attention as dynamic elements that could alter lighting conditions within single painting sessions. The impressionist understanding of atmospheric perspective went far beyond traditional blue-gray distance effects to include complex color interactions between sky and land.

Tree and foliage subjects allowed impressionist artists to develop techniques for suggesting volume and depth through color relationships rather than linear perspective. Artists learned to use warm colors to bring foliage forward and cool colors to push it back, creating spatial effects through pure color manipulation. The broken color technique proved particularly effective for suggesting the complex interplay of light and shadow within tree canopies.

Flower paintings provided opportunities for exploring pure color relationships in relatively small formats. Artists like Renoir and Caillebotte created flower studies that pushed color intensity to new limits, using complementary color relationships and broken color techniques to create vibrant, luminous effects. These works often served as color studies for larger compositions while standing as complete artworks in their own right.

The changing qualities of natural light throughout the day became central themes in impressionist nature painting. Morning light provided cool, clear colors and sharp shadows, while midday sun created intense contrasts and warm color temperatures. Afternoon light brought golden tones and longer shadows, while evening light offered dramatic color changes and atmospheric effects. Artists learned to work quickly to capture these transitient conditions, developing techniques that could suggest specific times of day through color relationships alone.

Weather conditions provided additional variables for impressionist nature studies. Rain created unique reflection effects and simplified color relationships under overcast skies. Snow scenes revealed the complex colors present in white surfaces and demonstrated how reflected light could warm shadows. Fog and mist offered opportunities to explore atmospheric effects and simplified form relationships. Each weather condition required different technical approaches and offered different expressive possibilities.

Revolutionary Impact on Artistic Tradition

The impressionist movement's impact on artistic tradition extends far beyond technical innovations to encompass fundamental changes in how art functions in society, how artists approach their subjects, and what purposes art might serve. The revolutionary nature of impressionism lay not only in its visual innovations but in its challenge to established systems of artistic training, exhibition, and patronage.

The academic system that dominated European art education emphasized careful drawing from classical sculptures and masters' works, followed by highly finished paintings of historical, mythological, or religious subjects. Students progressed through rigorous stages of training that could take many years to complete. The impressionist approach challenged this system by valuing direct observation over classical study and emphasizing personal expression over adherence to established rules.

Exhibition practices underwent dramatic changes as impressionist artists organized independent shows outside the official Salon system. These independent exhibitions, held from 1874 to 1886, demonstrated that artists could reach audiences without official approval and could present works that challenged conventional taste. The exhibitions also fostered group identity among participating artists and provided platforms for explaining their aesthetic theories to confused critics and viewers.

The role of art criticism evolved significantly in response to impressionist innovations. Traditional critics, trained to evaluate art according to established academic criteria, struggled to understand works that seemed to violate fundamental principles of drawing, composition, and finish. New critics emerged who could articulate the aesthetic theories underlying impressionist practice and help educate viewers about new ways of seeing and appreciating art.

Patronage patterns shifted as impressionist artists found support among new types of collectors. Middle-class patrons, including doctors, lawyers, and businessmen, began collecting impressionist works that reflected their own modern lifestyle and aesthetic preferences. This new patron base was less interested in traditional historical subjects and more attracted to contemporary scenes and innovative visual effects.

The relationship between art and photography underwent significant redefinition through impressionist practice. Rather than competing with photography's documentary accuracy, impressionist artists explored expressive possibilities unique to painting. This response to photographic challenge helped establish new concepts of what painting could achieve and contributed to the development of increasingly abstract artistic approaches.

Technical innovations in paint manufacturing supported impressionist developments while being driven by artist demand for new materials. The availability of portable paint tubes, brighter synthetic pigments, and improved canvas preparations enabled outdoor painting while artists' innovative uses of these materials drove further technical developments. This collaborative relationship between artists and manufacturers continues to influence how art materials are developed and marketed.

Art education gradually incorporated impressionist innovations into traditional curricula, though not without resistance from conservative instructors. The emphasis on outdoor study and direct observation eventually became standard practice in most art schools, while color theory based on impressionist discoveries became fundamental to artistic training. However, the integration of these innovations often diluted their revolutionary impact by incorporating them into conventional academic frameworks.

The concept of artistic series, pioneered by impressionist artists, influenced how subsequent artists approached their work. The idea that a single subject could support multiple artistic investigations encouraged artists to explore variation and development rather than seeking single perfect solutions. This approach contributed to the development of more conceptual approaches to art-making that would become central to 20th century artistic practice.

Market mechanisms for art sales evolved to accommodate impressionist works and the new collector base they attracted. Dealers like Paul Durand-Ruel developed new strategies for promoting and selling contemporary art, including solo exhibitions, published catalogs, and international marketing. These innovations in art commerce helped establish modern gallery systems and contributed to the professionalization of art dealing.

The impressionist emphasis on capturing contemporary life influenced subsequent artistic movements to engage with their own historical moments. Rather than retreating into timeless classical subjects, artists increasingly felt responsible for documenting and interpreting their contemporary experience. This shift contributed to art's increasing relevance to social and political discourse throughout the 20th century.

Contemporary Applications in Home Decoration

The enduring appeal of impressionist wall art in contemporary home decoration reflects both the timeless beauty of these works and their remarkable adaptability to modern living environments. Understanding how to effectively incorporate impressionist pieces into contemporary homes requires considering both aesthetic principles developed by the original artists and the practical demands of modern living arrangements.

Color harmony principles developed by impressionist artists provide excellent guidance for creating cohesive decorating schemes. The impressionist understanding of complementary color relationships can inform choices about furniture, fabrics, and accessories that will work harmoniously with impressionist wall art. Rooms decorated around impressionist paintings often benefit from neutral backgrounds that allow the artwork's color relationships to dominate while incorporating accent colors drawn from the paintings themselves.

Scale considerations become particularly important when selecting impressionist reproductions for home use. Large-scale impressionist works can serve as focal points that organize entire room compositions, while smaller pieces work effectively in groupings that create visual rhythm and balance. The impressionist practice of creating series suggests that multiple related works can be more effective than single isolated pieces, particularly in larger rooms or hallway installations.

Lighting design plays a crucial role in displaying impressionist wall art effectively, as these works depend heavily on their color relationships for their impact. Natural lighting that changes throughout the day can enhance the impressionist quality of capturing transient light effects, while artificial lighting should avoid color distortions that would compromise the careful color balances in these works. Many collectors install adjustable lighting systems that can accommodate different viewing conditions and times of day.

Frame selection for impressionist wall art requires balancing historical authenticity with contemporary decorating needs. Traditional gold frames can enhance the warm color palette of many impressionist works while providing appropriate historical context. However, simpler contemporary frames might work better in modern minimalist interiors where ornate framing could compete with clean architectural lines. The key is selecting frames that enhance rather than distract from the artwork itself.

Room function considerations influence how impressionist wall art can be most effectively used in contemporary homes. Bedroom installations might emphasize the more peaceful, contemplative works like Monet's water lily paintings, while dining areas could feature the convivial social scenes painted by Renoir. Home offices might benefit from landscape scenes that provide visual relief from close work, while entryways could showcase more dramatic compositions that create immediate impressions for visitors.

The psychological impact of impressionist wall art makes it particularly suitable for creating specific moods in home environments. The warm, light-filled qualities of most impressionist paintings contribute to feelings of well-being and relaxation, making them excellent choices for living areas where people gather for leisure activities. The outdoor subjects favored by many impressionist artists can help bring a sense of nature into urban living environments.

Integration with contemporary furniture styles requires careful attention to scale and color relationships. Mid-century modern furniture, with its emphasis on clean lines and natural materials, often works well with impressionist wall art, as both approaches value simplicity and direct material expression. Contemporary minimalist interiors can accommodate impressionist paintings when the artwork is given sufficient space to breathe and isn't overwhelmed by competing visual elements.

Grouping strategies for multiple impressionist works can create more impactful installations than single pieces displayed in isolation. Following the impressionist practice of creating series, homeowners might group related works that show seasonal variations or different times of day. Alternatively, works by different artists might be grouped according to shared color themes or subjects, creating conversations between different artistic approaches within the broader impressionist tradition.

Collection building strategies for impressionist wall art should consider both aesthetic and practical factors. Starting with high-quality reproductions allows homeowners to live with works while developing their understanding of what they most appreciate about impressionist art. As budgets allow, original prints, drawings, or paintings can be gradually added to create more authentic connections to the impressionist tradition.

Conservation considerations become important for protecting impressionist wall art investments over time. Proper framing with acid-free materials, controlled lighting exposure, and appropriate humidity levels help preserve both original works and high-quality reproductions. Understanding these preservation requirements from the beginning prevents damage that could compromise both aesthetic and financial values.

Understanding Impressionist Brushwork Techniques

The distinctive brushwork that characterizes impressionist painting represents one of the movement's most recognizable innovations and continues to fascinate viewers more than a century after its development. Understanding these brushwork techniques provides insight into how impressionist artists achieved their distinctive visual effects and helps contemporary viewers appreciate the skill and intention behind seemingly spontaneous paint application.

Directional brushwork became a fundamental element of impressionist technique, with artists using the direction of their brushstrokes to suggest form, movement, and surface texture. Horizontal strokes might indicate calm water surfaces or distant horizons, while vertical strokes could suggest upright forms like trees or architectural elements. Diagonal strokes created dynamic tensions within compositions and could suggest movement or unstable conditions like wind-blown foliage.

The pressure and speed of brush application created different textural qualities that impressionist artists learned to control for specific effects. Light, quick touches could suggest delicate subjects like flowers or distant atmospheric effects, while heavier pressure created more substantial forms and stronger color statements. Artists developed the ability to vary pressure within single strokes, creating marks that might begin heavily and fade to light touches, suggesting forms that gradually dissolve into light and atmosphere.

Brush size selection became crucial for achieving different visual effects within single paintings. Large brushes allowed artists to cover significant areas quickly and create unified color areas, while small brushes provided control for detailed areas or precise color placement. Many impressionist paintings show evidence of multiple brush sizes used strategically throughout the composition to create variety in paint handling while maintaining overall coherence.

Conclusion

The enchanting world of Impressionism wall art continues to captivate art lovers and collectors alike through its unique celebration of color, light, and emotion. As a revolutionary movement that emerged in the late 19th century, Impressionism broke away from the rigid rules of traditional academic painting to embrace spontaneity and the fleeting nature of moments. This artistic approach not only redefined the way artists perceive and depict the world but also transformed how viewers engage emotionally with artwork.

Impressionist wall art invites us into a vibrant visual experience, where brushstrokes seem to dance across the canvas and colors shimmer with a life of their own. By focusing on natural light and its ever-changing qualities, Impressionist artists like Monet, Renoir, and Degas created works that feel alive and immediate. This quality allows the viewer to feel the warmth of a sunny afternoon, the softness of a blooming garden, or the bustle of everyday life in a way that feels deeply personal and immersive.

One of the most enchanting aspects of Impressionism is its ability to evoke emotion without relying on detailed realism. Instead, the art captures impressions—moments of sensory experience—allowing the viewer’s imagination and feelings to fill in the spaces between. This emotional resonance is why Impressionism remains a favorite for wall art in homes, galleries, and public spaces. It can bring a sense of tranquility, joy, or nostalgia depending on the chosen piece, transforming any room into a space of contemplation and beauty.

Moreover, Impressionism’s influence extends beyond just painting; it has inspired countless artists and movements in various forms of visual expression. Today’s wall art, whether original works, prints, or digital reproductions, continues to reflect the core values of Impressionism: spontaneity, light, color, and emotion. This enduring legacy ensures that Impressionism will remain relevant and cherished for generations to come.

In conclusion, the allure of Impressionism wall art lies in its timeless ability to connect viewers with the fleeting beauty of the world around them. It offers more than just decoration—it provides a journey through color, light, and emotion that enriches the spaces we inhabit. Whether you are an art aficionado or a casual admirer, embracing Impressionism in your living environment invites a fresh perspective and a deeper appreciation for the magic found in everyday moments.